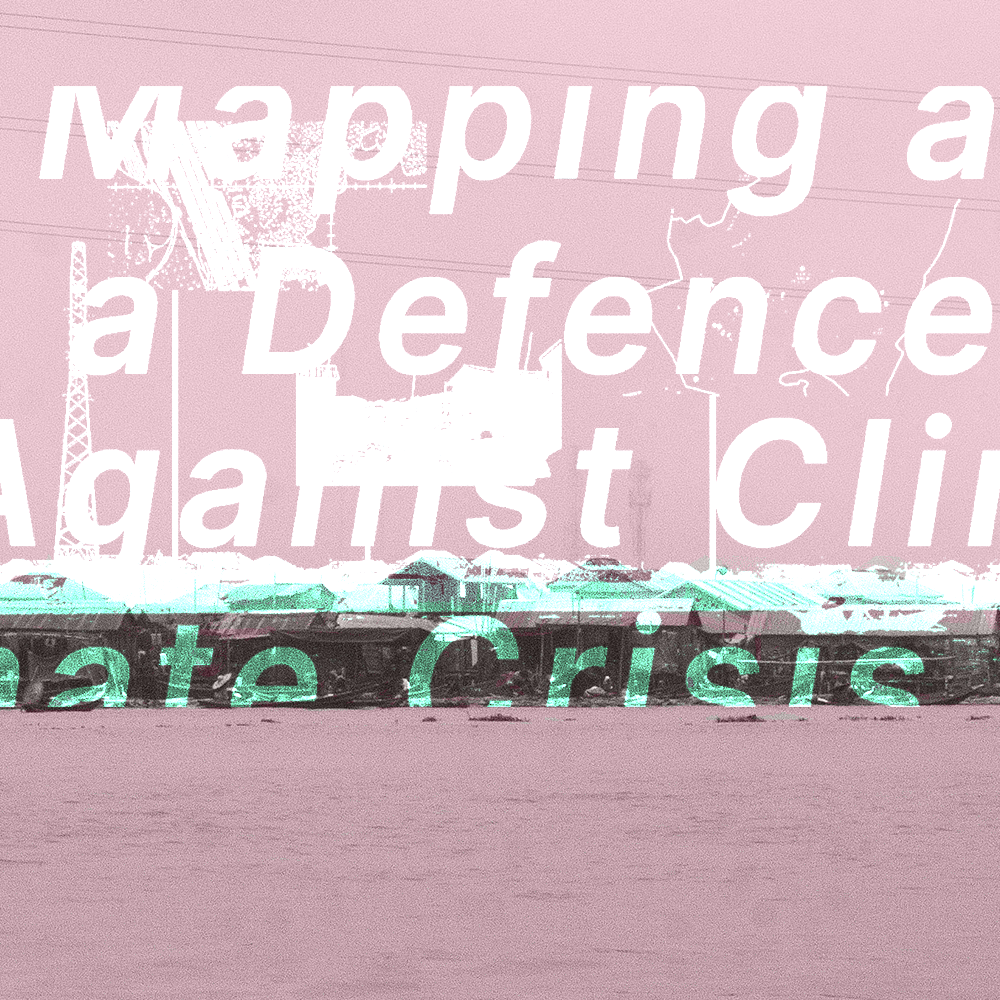

When forty-six year old Hosu Mausi first saw the map of Makoko, Lagos in Nigeria, he was full of excitement. Makoko had not been mapped so extensively before, and now the position of the Oluwatosin Mosque was marked at its exact place, clear on his daughter’s smartphone. The terminal where Mausi disembarked from his fishing expeditions at the lagoon occupied its rightful place. The location of the floating school, since destroyed by the strong winds from the Atlantic Ocean, was where it had stood, not far from the lagoon.

That same wind blows about Mausi as he smiles, recollecting that moment, stood on the shore in a blue dress, white cap and with beads dangling around his neck. He speaks with passion, flailing his hands in the air, exuding enthusiasm.

His passion over the map seems appropriate, Mausi fishes at the lagoon, and in the Atlantic beyond, and it is this mapping he sees as vital to resolving the poverty of Makoko’s distressed fishing families, who form ninety percent of the area’s population.

Aerial View of Makoko, Credit: Humanitarian OpenStreet

Makoko stands as one of Africa’s most extensive inner city slums, comprised of six villages, four of which float on the lagoon, having grown from a small collection of families from the Benin Republic in the 19th century, to a now estimated 250,000 people. Mausi’s house, as well of those of many others, consists of structures on water made with locally sourced bamboo, concrete blocks and other cheap materials, fragile constructions in a harsh environment.

Maps and this type of social geography then assume importance to the recognition of Makoko, but, as climate change is factored in, also provide a way to respond to changing fishing landscapes in the area. The information now available to fishing crews can aid them in making informed decisions, cognisant of rising sea levels and water temperatures, the data of the maps being integrated with weather and water monitoring technology, creating an early warning system for future unusual conditions.

According to Mausi, in the past, crews at Makoko had caught as much as one-hundred-and-twenty kilograms of fish per day, but, they found it difficult today to catch even forty kilos, with fish fleeing the local area. Mausi recalled catching croaker, mackerel, tilapia and sharp-toothed barracuda, his crew piling fish unceremoniously into plastic buckets and taking them to the internationally famous Makoko fish market. Now, however, a crew of fishermen may make just $11 USD per day.

Makoko fish market, Credit: Deolusamuel, CC BY-SA 4.0

As the amount caught at Lagos lagoon dwindles, and with government indifference to the problem, the financial troubles of local fishing crews only increase. While Nigeria’s fish demand stands at around 3.6 million tons yearly, local production now brings in only 0.9 million tons, leaving a deficit that ends up being imported.

To make matters worse, flooding, induced by the extreme weather, and accompanied by oily black water from waste disposal, impacts negatively on the fish themselves. Makoko contains huge dumps of waste, typical to fishing settlements, and as these seep into the water with flooding at least three times a year it leads to reduced oxygen levels and poisoned habitat. Not only this, but navigation of the canals in Makoko is further impeded as water lilies grow on the back of this flooding.

Despite all of its presence in the story and living development of Lagos, Makoko had remained a blank spot on the map throughout its history, invisible, and thus making it impossible to engage with fishermen such as Mausi to plan measures of climate adaptation and mitigation, or support their development.

Community Mapping

Maps of Lagos dating back to the 19th century show the concern of various generations and imperial powers with understanding social life in the area, and through this also incorporated and made official its social exclusions. One of the most extensive mappings of Lagos, by the US military, a compilation of maps from across the prior decades, does make place for Makoko and yet, because of its infrastructure, the area appears as a white splotch. This history of exclusion is also likely down to the status of Mausi’s great-great-grandfather and others, having newly moved to the area from the Benin Republic – poor and unimportant.

US Army map of Lagos, 1962

The historical mapping project ‘New Maps of Old Lagos’ tries to reveal the history of the megacity via its maps, going into several layers of mapping to chart for instance the effects of the bombing by British Navy in 1851, or the history of trains on the Marina. But, with its lack of mapping history, Makoko is not a likely or viable prospect for such unveiling.

Specific community mapping to cushion from these exclusions is a more recent development in cartography, as show by Madhuri Karak’s work charting efforts in Indonesia. And in 2019, following these trends, Makoko’s mapping project began.

Jacopo Ottaviani and John Eromosele led the map-creation, on behalf of Code For Africa, a non-profit organisation focused on civic technology and digital innovation, engaging the community on how to proceed. The training for the project then took place in November 2019, with Code For Africa and groups like Makoko Dream and African Drones teaching thirty-two Makoko community members how to their operate mapping drones and smartphone software.

Before the training could begin, community elders approved the intents of the project, and assigned Tobi Aide, son of one of the traditional rulers, to support Code For Africa on the efforts. In an unfortunate example of the risks being mapped however, during the project, floods swept away Tobi Aide’s house. He had to rebuild as it continued, increasing the gap between the bottom of his shack and the surging water flows. An indication of the true stakes of the project.

Drone Mapping

Mausi’s daughter was one of the volunteers in drone mapping, alongside a bunch of the volunteers being girls looking to learn and familiarise themselves with the technology. This way Mausi received feedback on the project when she finished the training or assignments at the end of the day. Through her he would learn how the volunteers and project leaders mapped streets, waste dumps, churches, mosques, schools, boat terminals, houses and more.

Makoko canal street, Credit: Page Tsewinor, CC BY-SA 4.0

The young volunteers used drones operated from canoes to collect the visual data, as well as gathering geo-data via GPS and Open Data Kit to build a detailed map of Makoko. This presented challenges peculiar to the area, navigating their way around waste, through narrow, tricky canal passages and perching on the edge of canoes. One Tuesday evening, while returning from a fishing trip on the lagoon Mausi saw the volunteers seated on the side of their canoes, busily gathering data with their phones, while oil-polluted water rippled about them.

Sometimes, they gathered data with evidence of climate change on full display, the water levels rising so high that they could easily be swept from the boats and into the bulging canals. Mausi would find his daughter at home on some days, unable to go out for mapping, the risk simply too high.

The information for the map was not only collected via technological means either, as they also researched names of streets from community members, giving some locations names, pin-pointing structures that were former blank-spaces, filling out the details.

The community map created by the volunteers can currently be accessed on OpenStreetMap.

Community Map of Makoko, OpenStreetMap

Mapping for the Future

Researcher Dr. Philine zu Ermgassen has written that the use of mapping in this way, in the mangroves of Nigeria’s Niger Delta, could greatly enhance both policy and management interventions. She could well have been saying the same thing about Makoko.

Its creators posited this as their goal. “One of the intentions behind the map was response to emergencies. The map could be useful in the case of the climate crisis: with rising sea levels, people are facing huge problems,” Ottaviani told me.

Makoko from the water, Credit: Ayorinde Ogundele, CC BY-SA 4.0

Sitting in his canoe, just as he had watched the volunteers map Makoko, Mausi agreed with Ottaviani’s view of the project. He himself sees the map as serving as evidence of Makoko’s environmental challenges, as well as a document for their right to exist in the likely case of disasters brought by climate change.

The words of Eromosele speak to the urgency behind the work. “We should prepare our map in the days of peace. Maps help us to make informed decisions, their baseline data can be integrated with tech solutions to create early warning systems and weather evolutions.”

This has been Eromosele’s intention in following up on the project, leveraging the map data to access information on drinking water sources, collecting samples for analysis, discovering very high acid contents in the drinking water across Makoko’s villages.

Through the map, and examples like this, Mausi feels that government and Makoko’s community itself not only has a document to devise a plan in response to climate change, but one that addresses local resources. It’s a project that, like any map, changes the world it is based on, filling out the gaps of acknowledgement required to see the potentially deadly effects, as the planet itself changes too