In 2020, Container published a long read on the pandemic’s effect on live performance. We spoke to people involved in theatre, music, and across cultural events about the breakneck evolution of live events, the pace at which new models were tried and adopted and the innovations that emerged under pressure. Two years on, we’re going back to ask how things stand. What was temporary and what’s permanent? Has access to events changed for good? What was learned along the way?

Live streams and live spaces

The pandemic pushed many live events organisations to start broadcasting online. In the wake of this shift, Emma Rice’s touring theatre company Wise Children came out in front to publicly commit to incorporating live broadcasts into their programming not just for the pandemic but into the future. “You make lots of assumptions about why people don’t go to the theatre,” Technical Director & Digital Producer, Simon Baker says. “You can think it’s financial, or access issues – all kinds of things. But we realised everybody [who contacts us] has a bespoke reason for why they can’t see a show… Everybody’s reasoning is very different. If we didn’t do it, who knows what percentage of our audience we’d be missing? Huge, probably more than those that do come. ”

Wise Children’s live streams are run similarly to a show’s technical rehearsal, Baker says, and their model streams, and records a filmed version to be sold on to an outside broadcaster such as Netflix or Sky Arts. They’ve found ways to leverage the technology that extend to aspects such as marketing and schools programmes. “It means people are used to it being around now” he says. “Cameras in rehearsal rooms used to feel really intrusive, now they’re the norm.”

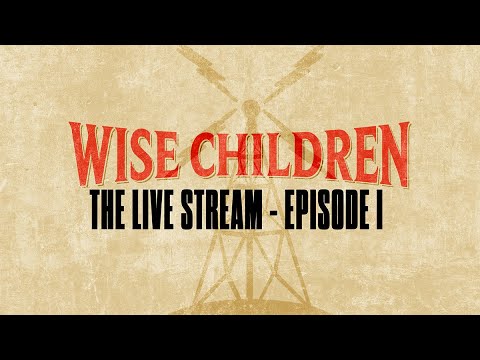

Some music venues and festivals that moved online expanded their output inventively to access international audiences. Glasgow experimental music festival Counterflows, run by Fielding Hope and Alasdair Campbell, developed Counterflows At Home, an online programme that included commissioned documentary-style films, podcasts, long-form articles and a zine. It offered a distinctive offering to many other independent music festivals, many of whom live streamed shows. Hope says they didn’t feel they wanted to compete in that sphere, when he was aware of everyone having too many browser tabs open already. They were also conscious of creating something that had value into the future and that “felt like an expansion of an artist’s practice,” he explains. Their expanded zone of the festival also became a way of creating content that renumerated creators properly instead of “flinging them £100”. The festival returned in 2022 as an in-person event, but retained Counterflows At Home. “Neither of us is into live streaming,” he says. “Moving back to in person was the main desire, because that’s the heart and soul of the festival. But we realised the content was resonating with an international audience, and with an audience that either can’t afford to come or just can’t physically come for various reasons.”

Counterflows at Home programme (screenshot from website)

The significance of being in the room was also reinvigorated for Hay Festival, says its Chief of Staff Adrian Lambert. “What’s always been important about Hay Festival, even when you’re broadcasting events, is the fact that they are happening in such a remote rural town,” he says. “The live physicality of the festival – sharing a space with an author and with other human beings, in a very rural part of Wales – is part of what makes the Festival so special.”

Hay Player (screenshot from website)

In 2021 they setup hybrid spaces that looked to traditional broadcast techniques emulating chat show formats, rather than Zoom-led spaces. This year, they video recorded their top three venues, and audio everywhere else, capturing 700 events on audio, and around 100-150 on video, but Lambert says that he knows Hay Festival is a live event first and foremost: “The risk is you resort to being a TV production company,” he says. “A live literature space is fascinating. Why do people want to share spaces with authors, writers, artists? What does that live space give people?”

Experimentations with form

This idea of liveness is crucial to theatre and has been a focal point of companies’ thinking on how to deploy technology and streaming to retain this. Amber Massie-Blomfield, Executive Director of international touring theatre company Complicité points me to Can I Live? by Fehinti Balogun, a show about climate justice that was intended to be a live stage show, but that was converted to a filmed performance when lockdown hit, incorporating elements such as CGI. It ended up seen by various community groups in unofficial screenings they arranged themselves and has allowed them to access non-traditional spaces that wouldn’t usually be possible for a touring theatre group, not least (for a work about climate justice) at the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, and at COP26. It also posed challenges for the way they described it: “It fell in this interesting space between being a theatre piece and a film and I don’t think we ever quite found the language for what exactly it was,” she explains. Currently, they’re working towards a theatre version of Olga Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead, co-produced with Bristol Old Vic, which deploys filming methods borrowed from live football. “When you screen something, it takes an essential element of what theatre is out of the equation – there’s such a fidelity to the idea of liveness and how essential that is to theatre,” she says. “But creating something else, in an art form that sits between film and theatre, is a really interesting place to play. How can you create a sense of liveness in that context for those audiences?”

Film still from ‘Can I Live?’

This liveness doesn’t necessarily need pioneering technology like the RSC’s AR productions like A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which used features like motion capture to create avatars and immersive environments. It is about a nowness and shared experience. She points to a piece from theatre festival Gift, where audience members were instructed to take an ice cube and hold it in their hand. “It was so physical,” she recalls. “It was about presence and time. We’re all over the world watching this piece, and yet we’re all having this same experience.”

Massie-Blomfield says Complicité, like everyone Container spoke to, is trying to work out what a sustainable business model looks like. “All the data you have either predates the pandemic, or was during the pandemic, which were different worlds,” she points out. “No-one has quite figured it out yet.”

The search for a business model

Everyone spoken to for this article said that the business models remained unclear. In particular, live music completely lacks a functional business model. Mark Davyd from the Music Venues Trust says: “There is an overarching reality of where live streaming currently sits. People have not – so far – been offered something they consider to be of sufficient value to justify paying a price to access it, which generates enough income to fund creating it. It serves functions around inclusivity and marketing, which have led some venues to continue with it. However, we don’t have an example of any grassroots music venue which has continued the work they delivered during Covid where live streaming was a principal source of income for artists and venues. If people can go to the show, they want to be there… Live music is a physical, interactive and engaging activity which cannot be replicated fully by an online experience.”

One exception to the search for a business model is Lost Horizon, a warehouse venue in Bristol that also has a digital twin in the metaverse, run by the team behind Glastonbury’s Shangri-La. A combination of lasers and cameras converts performers into avatars in the venue’s digital twin to perform in real time. It’s currently in beta, as it’s hitting the limits of what VR can do, but exists as a showcase and proof of concept. “We wanted to focus on the digital twin concept so it’s not detaching people from reality,” says Robin Collings, CEO at Lost Horizon and Director of Shangri-La. “We want to connect with people, not create an escapist or fantasy world.”

Collings says there were two key motivators for the digital twin format: “Firstly, the social nature: with social VR we can actually communicate and make proper connections,” he says. They considered worlds that were, for example, cuter or blockier, but chose realistic rendering: “The other thing is the fidelity of the experience: you can authentically represent art or photography or performances in this digital space.”

Their first forays into VR were spaces built in the metaverse during the pandemic, to which around 10,000 people attended (in VR). Those spaces still exist (they were built in a different VR platform) so pandemic performances are looping, meaning you might catch a performance by Peggy Gou if you roll up at the right time. They’ve found audiences are disproportionately large in places with lower densities of cultural activity such as parts of Australia, or where culture is restricted, like in Iran. “In December 2020 we did a VR show with a band called Infected Mushroom, who have huge audiences in Israel and Iran,” says Collings “It was specifically about bringing these two audiences together in a shared experience, when they might have been taught to see each other as alien. I cried several times walking through that show. There’s some amazing potential in that – 7000 people were there.”

Infected Mushroom show

Lost Horizon festival space

Withdrawing access

However, for people with disabilities or access issues, this widespread uptake of remote events has been bittersweet. Katouche Goll is a PR and creative contributor with a focus on diversity and inclusion. Born with Cerebral Palsy, she is also an artist and online content creator. She notes that during the pandemic, there was a problem with the motivations for opening up remote events: “The issue is that creating a virtual context has never been framed within the context of accessibility,” she says. “It’s always been framed within mainstream society’s needs. [During the pandemic] it just so happened to support what disabled people needed.”

The virtual option offered by the pandemic was, she points out “an invaluable resource for more equitable participation” but is only considered standard practice because now, everybody else needs it. “Disabled people would have always benefited from having a virtual option or hybrid option,” she says. “Now that’s being taken away, it says that some people can participate in society and others should have to make do with going without.”

Grace Quantock, a writer, researcher and psychotherapeutic counsellor, who is a wheelchair user Container spoke to in 2020, echoes this: “It’s really painful to see access being withdrawn…” she says. “Things are swinging into a backlash against online working, which is ableist and problematic in multiple ways – I’m seeing people saying something is just better or more easier in person – to which I often mentally add, ‘for you’. People are already forgetting how it was when you couldn’t attend in person. I’m being told it’s not possible to have remote or hybrid events now – but it was possible just a little while ago! I can’t emphasise how difficult and painful these conversations are advocating against being excluded and isolated, when people withdraw or aren’t providing access.”

Anything but ‘normal’

What’s clear across the board is that there has been no ‘return to normal’. The idea of liveness has been tested, the technological feasibility of remote access has been proven, and hybrid live forms emerge from both implementations of pioneering technology, but also through smart use of existing tech for storytelling. This might use what you have in your pocket, as with audiovisual drama iMelania, which happened on stage and through your phone, or pioneering VR and AR like Abba’s Voyage tour, where the band created full-blown avatars (ABBAtars) of their younger selves to perform ‘live’. Underlying these opportunities, are potential future upheavals to culture, from effects of the war in Ukraine to winter variants and the energy crisis.

Back in 2020, Tarek Virani, an Associate Professor at UWE Bristol was in the middle of research looking at resilience in small creative and cultural business in South-West England, with a view to building a future toolkit. When the initial research was completed, they isolated nine key markers indicating businesses could survive shocks. Some of these made obvious sense, such as having a hybrid business model, or one that could pivot online and generate significant revenue. This meant, for example, a theatre company running online classes while their productions were shut down. Other markers for weathering the pandemic included having an agile workforce: freelancers rather than employees. Interestingly though, collaborations and networks proved crucial, as did working on R&D. This latter finding meant businesses did better if they could test new ways of working, like Lost Horizon have done, and access funds to do so. If there is an optimistic note to be struck, it’s that testing new technologies is good for creative practices, although there’s unlikely to be plain sailing ahead. What Virani emphasises is that their findings hold for any destabilisation of businesses, not just the pressures of the pandemic. “Having this type of toolkit, and these indicators, I hope will be useful for creative businesses in future, across the board,” he says. “There are a number of external shocks waiting in the wings.”