The Sounds of the Body

It’s a hot, humid day for each of the interviews I take, the coastal summer being ever present in the background, wet and sticky. The hottest year on record, again.

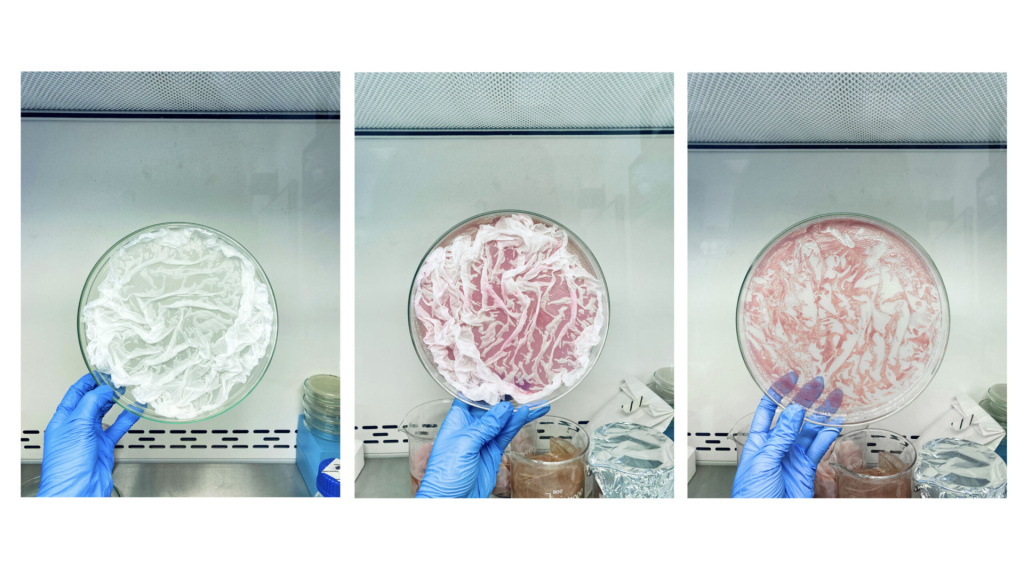

I see Kexin Liu at the open studio event First Friday, the Pervasive Media Studio in Bristol’s monthly exhibition of a curated selection of studio resident work. She has set out a table with fabrics, a book and a record now spinning, pulling each item from an intricately crafted pink box. This is 3607_Bacterial Soundscape (2022-2023).

3607_Bacterial Soundscape, Kexin Liu (2022-23)

Looking closely with a bunch of curious visitors, each surface is layered with intricate dye patterning. These are patterns made by bacteria samples grown from the human body. Silk lain across the cultivated samples of dye producing growths.

Kexin writes that the project comes from a feeling of a loss of control of self, and searching in the microbial for a relationship with the organisms we co-exist with, those that impact our feelings. The project’s overarching form is as a soundscape expressing the multiple selves and others harboured within our cavities, the process of creation the growth, analysis and division of bacterias into known and unknown strands, as measured by whether they had been recorded before. Sounds are allocated between the two sets as they appeared in the various parts of the body.

It’s a visually sleek, professionally assembled piece, designed to look at, and I’m glad it got the chance here, as previously in Edinburgh and Eindhoven, since, as Kexin tells me, the dyes of the work themselves deteriorate in light as they’re shown. Its posterity, like any biological matter, only preserved for so long.

3607_Bacterial Soundscape, Kexin Liu (2022-23)

While I think this an interesting way to explore the ideas, when we talk she says that, in showing the work, there’s a kind of frustration that comes with having to explain it and how it was made, wanting to make something that speaks for itself.

I observe a discussion between her and a visitor as they try to establish how ‘scientifically’ the sounds were created, and seem disappointed with the fact that the work is a piece made by a person poetically responding to data, as if it would be more interesting if the bacteria themselves were performing the instrumentation. During this interrogation I feel like I get what Kexin means about not needing to explain work to people.

On the other hand, seeing as she shows me the pressed silken pattern trapped in the material of the vinyl disc, it can be useful to be given a closer look. In the studios the sound of chattering somewhat drowns out the soundscape, so I listen to it from my laptop.

When I listen at home I am surprised by how alive the two networks of sound object make each other feel, the known and unknown spectra of the body a radio station you tune in to at the far end of the available airspace, each track like a bubbling pot being struck with discordant tools, an internet server, an aerial picture of a city, a fire. The tracks sing with chittering wings and gameshow effects, cavern filling tones and static buzz, glorious and unsettling, overwhelming, the sheer noise of the body. I feel like I need to experience these sounds in a resonating space, a public exhibition that gives over to them the direction of the space, rather than a quest via their creator to tease out ‘How was it done?’

3607_Bacterial Soundscape, Kexin Liu (2022-23)

I think the situations created by art exhibition and research art can leave people searching for an ‘explanatory’ key to the work. This work, with its roots in seeking explanation and then looping back into artistic expression, I think gets to the discomfort of the impulse of seeking to scientifically explore the truth, and it being something that will loop back each time with the realisation that explanation is not resolution. That the sounds themselves, the patterns on the fabrics themselves, are the speech of the body.

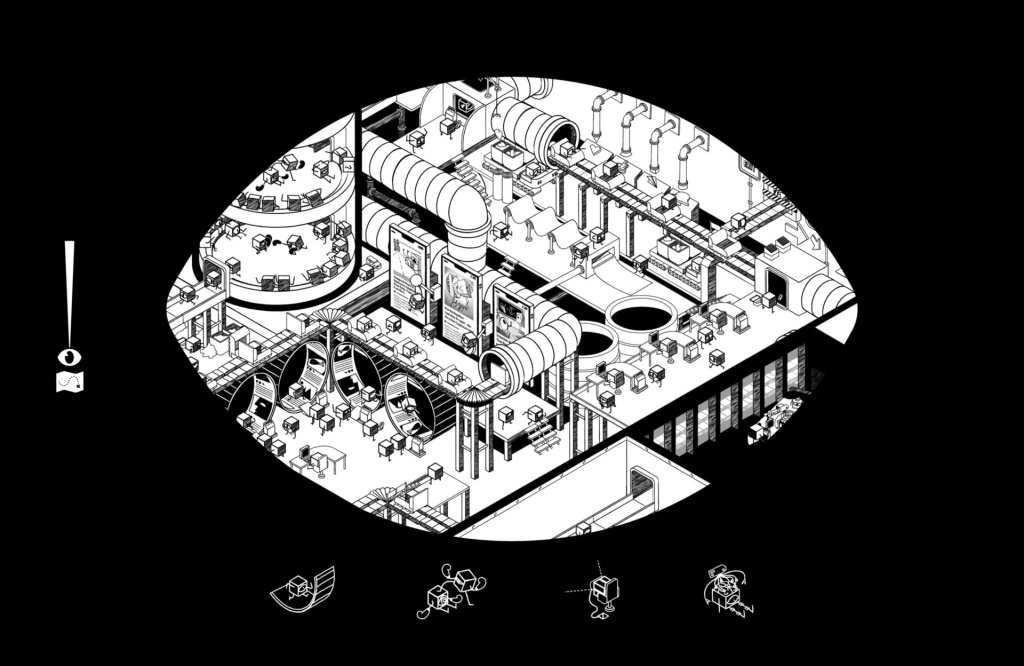

Kexin’s recent work is as Project Director on Focus, But Where? an art game exploring, ambitiously, living in a world dominated by a human altered climate, and tempered by the algorithmic and propagandised news cycles that surround this. From concept and art alone its integration of these ideas goes beyond drawing attention to the climate, with a focus on the economies of media production, policing and technological attention that effect the actions we take.

It seems fascinating, and I am really interested to see how Kexin’s practise in 3607_Bacterial Soundscape, one that has produced a beautiful, confounding creation, is reflected in something engaged directly with addressing the cynical, deadening effects of the protection of pollution.

Focus, But Where?, Kexin Liu, In collaboration with Kai Charles, Inigo Hartas, Xingzhi (Gigi) Zheng (2024)

The Instruments of Science

Kexin’s work was supported by the ASCUS Lab at Summerhall in Edinburgh, and it’s there that I looked for more artworks coming out of this mix of science and art.

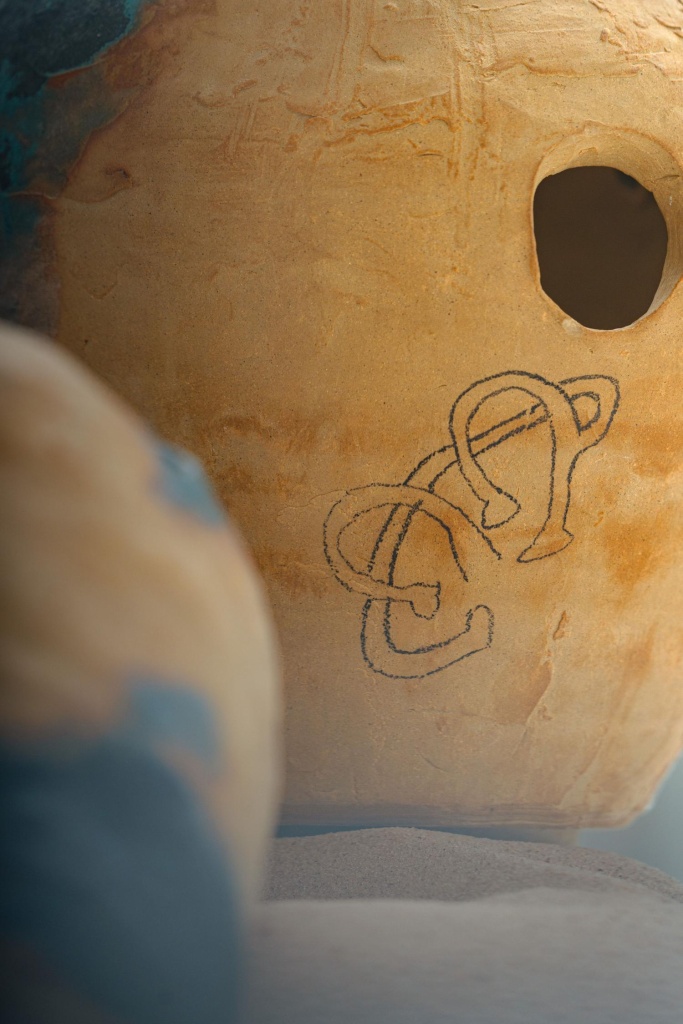

I found, once I got to Scotland for the Glasgow International Festival of Contemporary Art, that I’d just missed the chance to see the work of Emma Hislop at the ASCUS supported exhibition for Edinburgh Science Festival. From documentation online, the exhibition Mythic Instruments drew me in with the sculptural, sand buried forms of technologies with unknown purpose and origin. Inscribed with alchemical symbols, glass and pottery, held in cases. The displays are gorgeous.

Looking at more of Emma’s work I see this clear thread of scientific historiography, alchemical and research based projects that I am curious about the origins of.

We arranged to chat on the 4th July, the day that the UK would hold its general election. Just back from the polling station, I logged in and opened our Zoom call. For the next 15 minutes we went back and forth in a pantomime unable to hear each other and trying to fix the problem. Eventually I got through.

Emma works out of the Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop, where she conducts a research based material practise. I asked her about the origins of the scientific process in her work.

“I would say that it’s always been how I thought. Like I’ve always, ever since I was really young and really into the kind of mythical nature of science, and much to my parents displeasure, did not go into science, but did go into like the kind of exploration of… like just the kind of mysteriousness of science always intrigued me, and the real close tension between fact and fiction. Everything scientific is always a theory, it’s never fact.”

Mythic Instruments, Emma Hislop, Summerhall (2024) | Photo: Olive+Maeve

Other influences that are mentioned are Macbeth, Japanese folk tales and the lives and myths of plants and looking for threads that draw each thing in the web of research together that then spark into life as art.

“I feel like there’s something that I’m always kind of chasing, this like connection between things that I have never quite discovered. And I don’t know if I ever do want to discover, because it might just ruin everything for me. But I’m still insatiably hunting down what this connection is, between the kind of mythical, and the alchemical, and these kind of traditional knowledges with plant life, and ecology, and how it all wraps together for me.”

The way that stories are formed from elements of science and myth, is at the heart of Emma’s approach to displaying reflections of science, and the sculptures in Mythic Instruments do have a science-fiction feel to them, a reason I was drawn to them. I mention this to Emma saying they’d reminded me of Dune.

“Well I do love Dune, as you can tell.” She laughs, “I really like playing and the kind of sci-fi side of it. Or, you know, I like to think of all my work as being semi-fictional rather than being semi-truthful. I like to try and like create worlds for people to get lost in, so they’re kind of transported a little bit, which is why I always lean into installation, which is never intentional but always happens. Rather than having people come in and study an exhibition as though it’s a museum, I want them to walk away with something that eats at them.”

I ask how she got into creating the material side of the work, and how this was done first off out of a DIY passion for making that has developed over the past few years, while looking for outlets for research.

“So, for instance, I was really tangled up in my head after lockdown because I had done too long a period of research almost. Too many things, too many strands. And then I went on a residency to Denmark, to this sawmill, and it’s like a steam powered, kind of abandoned sawmill in the middle of absolutely nowhere, where I didn’t know what I was doing.

And then I cycled around and was just picking plants. And I started making cordage, like just making rope of plants I was coming across, for ages, because I didn’t have anything. I didn’t know what I was doing. And then one day I found this old flax museum, and it’s a working museum with 50 volunteers who averaged an age of 102, one of which who spoke English. I can’t speak any Danish. And that just brought so much together for me and unpacked so many really important things for me, and brought a lot of the research I’ve done, especially into rushes, back to the forefront and back where it needed to be.”

“The absolute best part is then when I’m in the workshop, doing material experiments is when I feel most at home, and I always feel like I’m doing my absolute best work. But I can only do that from going through everything before and doing field research on a residency, or some kind of experience with an expert, is like the most important part.”

This stumbling into being in the right place at the right time for a work to emerge is very relatable to me, and I am inspired by the urge to follow interests down the path towards the people with the expertise that Emma has. I’d like to embody that more.

As I ask about the environmental aspect in her work, there’s a similarity in how interested both are in the communication of science currently.

“I think in the beginning it was always there. But I think in the beginning I didn’t really know what [ecology] meant, and how principled you need to be within that. And doing the reading, and discovering people like Mark Fisher, I just kind of started to find my own understanding of what ecology is and how that fits.

I felt like I need something to it of drawing attention to both the kind of communication of science, and the things we don’t get to see, and like drawing people’s attention back to what’s going on around us and this like unseen mess. Like, although you may be a tiny cog in this great big machine that, you know, you’re still important, just the same as a single rush.

And I think that’s probably why I got so into rushes, as they’re unimportant, and people just hate them, and they’ve been historically seen as this useless, but then were also, previously, incredibly valuable. So I’ve always felt like a return to previous knowledge is what we need and the only way to do that is through understanding ecology better.”

We talk more, about much more than I can fit here, but with each anecdote of her spontaneous learning, gathering, experimenting it’s clear Emma’s work has to it a complex and rich depth, and I’m excited to see where it goes next.

Mythic Instruments, Emma Hislop, Summerhall (2024) | Photo: Olive+Maeve

The Human in the Machine

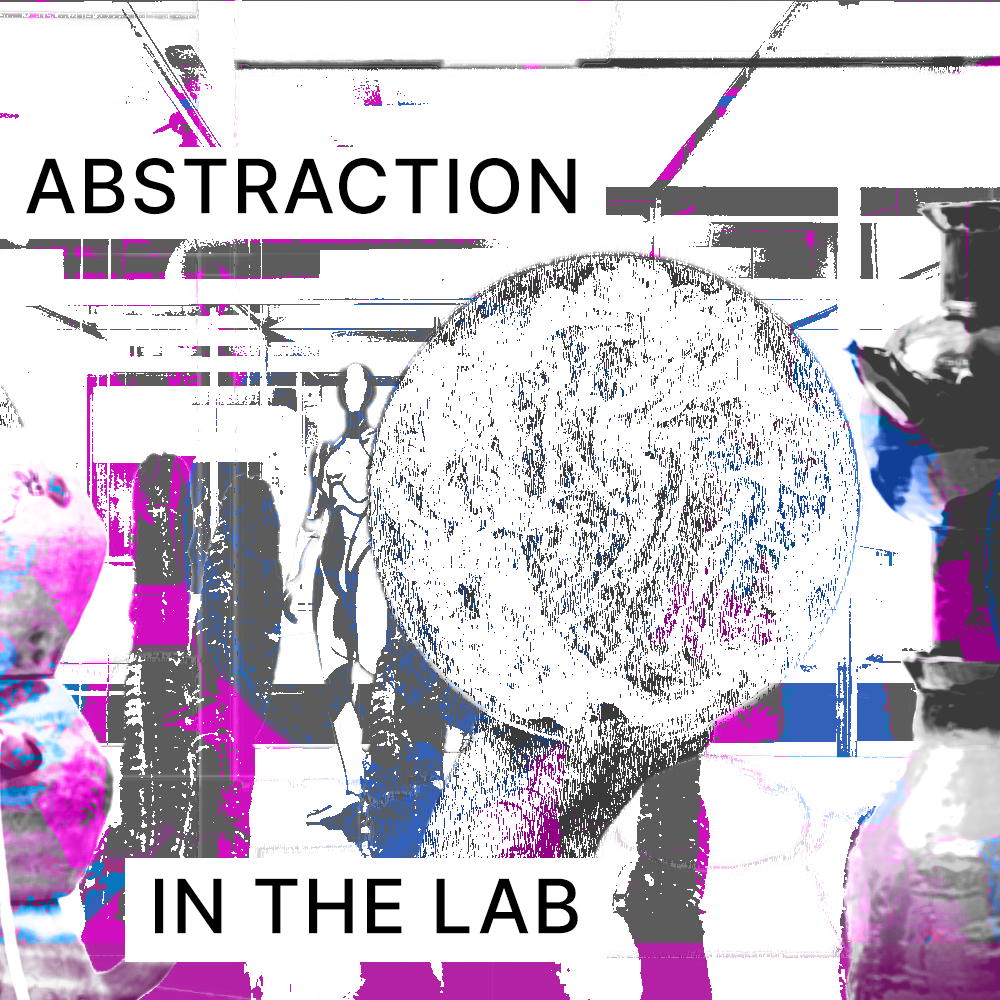

On my way back down from Scotland I learn of an exhibition in Birmingham, a collaboration between scientists and artists at the Centre for Systems Modelling and Quantitative Biomedicine, at the University of Birmingham, shown at Centralia in Digbeth. I see that the artist Alex Billingham is involved and so ask to talk to her about her work for the exhibition, ANNA.

We connect on a cloudy day, with it coming up to the evening. My mind is cooked, by the humidity and my ADHD, and I am grateful to see in Alex’s catalogue a work exploring the experience of neurodivergence, a thing that I am glad we can share in.

I had been talking to Alex earlier in the year about work with nuclear facilities, chiming with the research me and Morgan Jennings had done earlier in the year, it’s a topic she says she keeps circling back to unwittingly, and one that for both of us fascinates with its cultural history.

I was interested to know where this work with the scientific lab at Birmingham had come from.

“[The project] basically gets a whole bunch of scientists who are interested in doing sort of seed funding for various projects, with part of it being an embedded artist with that project from the inception. So I got to work with a whole bunch of scientists on robotics and neuroscience, looking at how specifically how AI and humans see the world.

ANNA, Alex Billingham (2024)

The project takes the form of video collage, a combinatory exploration of a three dimensional game world and filmed explorations of a garden park, with Alex’s performance as lycra-clad, LED faced and puppet-headed android type explorer. The data feed is a learning tool, the exploration a funny, highly stimulating kind of robotic patchwork.

I write this drinking something called Pepsi Electric, a bright blue fizzy drink, I can’t help but think of how we are, as in ANNA taught to reinterpret ourselves as machines. I bring up to Alex that I liked her work Word Soup, for how it presents the experience of neurodivergent learning as a kind of collage method. For her there is some validation in both projects.

“It was really nice because it was my first, well, second time working with a museum collection, approaching it from a position of ‘I don’t need to be in academic research’. And so the way that I’m interacting with it, connecting with it is an absolutely valid response to the collection.”

Word Soup, Alex Billingham (2022)

Like Emma and Kexin, there’s a wide range to the work that comes with a research based method for Alex. I ask where that comes from.

“I think it’s wanting to work out how to do specific things, so like, I do the soundtracks for my work. Partly because I’m after a specific kind of sound. A very 1970s sci-fi kind of soundtrack, all of these have this legal copyright on it. [Doing it myself] I haven’t got to worry about licenses and renting out all the music, but can still have all the connotations. And it’s the same with a lot of other bits. It’s like you just learn how to do that and then fold it in, and usually try and get a project to pay for it.”

For all of her work there is this background of the public information aspect of science alongside what she states as ‘nurturing an obsession with outdated hopes for the future’, this phrase acts for me like a codex, seeing through the performance collage method of the work the matching of communication, the nervous excitement of ideas posed as scientific, and the energy required for survival.

“Yeah, I think there’s something quite sweet about outdated scientific models that don’t work and we know they don’t work, providing obviously they’re not used for abuse. I think it’s very useful when looking at current thinking on science because it’s that level of… this is totally how we’re understanding things now, but in 20 or 30 years time this is going to be this ridiculous, outdated thing. [It’s important] I think being able to kind of have space for things not necessarily working as they should, but working enough that we survived.”

ANNA, Alex Billingham (2024)

For Kexin, Emma and Alex the matters of scientific inspiration, of laboratory collaboration and artistic expression also come down to being matters, essentially, of communication.

It makes sense, that, with a medium like science this becomes a predominant concern. The clarity or confusion of scientific explanation, the power that science has developed over what is considered empirical information, and how it interacts with our lived experiences of the world, is this vast, weird, scary information sector. An international interest in controlling narratives of science, for various reasons, has accompanied the colonial, capitalist violence that has led us to where we stand today. Now, staring down the climate crisis, the weapons of information are used to obscure.

In my mind the abstract, the semi-fictional, the collaged all have an important part to play in challenging what is often the intentional use of narratives around science to enforce existing power structures, and so work like this is vital