A massive collection of new media art spreads across the Internet’s global server network. While profit-hungry white cube galleries have made cynical attempts to extend ownership over digital artefacts, new media formats are used for free expression by a growing swarm of artists unwilling to compromise on their ideals.

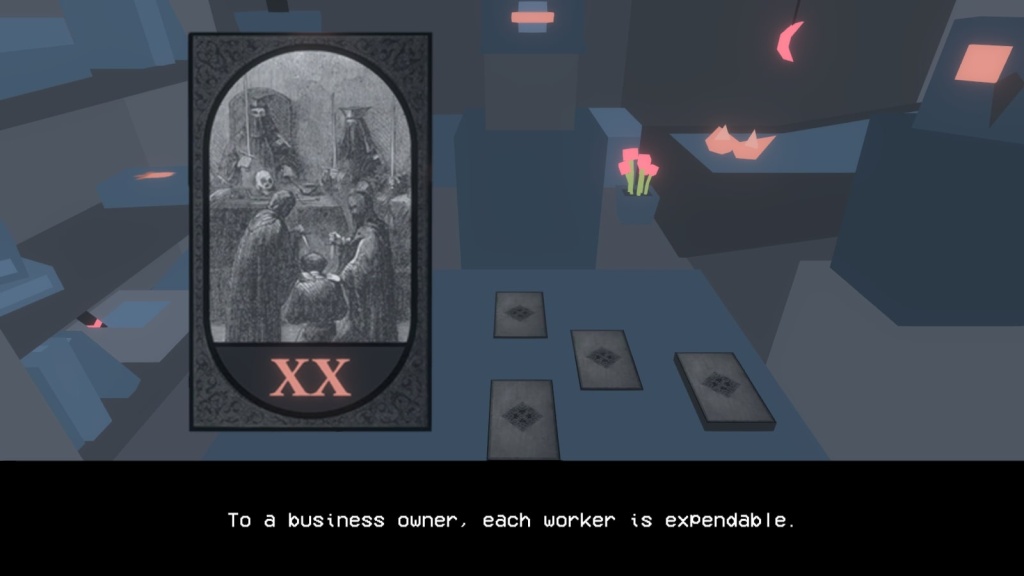

Cassie McQuater’s text file moreToMe.txt celebrates the format’s inherent possibility of infinite reproduction. Brenna Murphy’s website hosts publicly viewable audiovisual artwork from her years-long practice. Colestia’s video game A Bewitching Revolution tells the story of a communist witch building an anticapitalist movement.

Each item of new media art is part of cultural heritage imbued with a politics of resisting structures of enclosed infrastructure. However, amidst this, the format’s ephemeral and oft conflictingly privatised nature means that it can be difficult to archive, which makes finding ways to do so necessary.

A Bewitching Revolution, Colestia, 2019

Technology and the profit motive

While digital media like videos, websites, computer programs, sound files, and images can have the advantage of unrestricted access, much of the technology is subject to decisions made by for-profit companies and national governments.

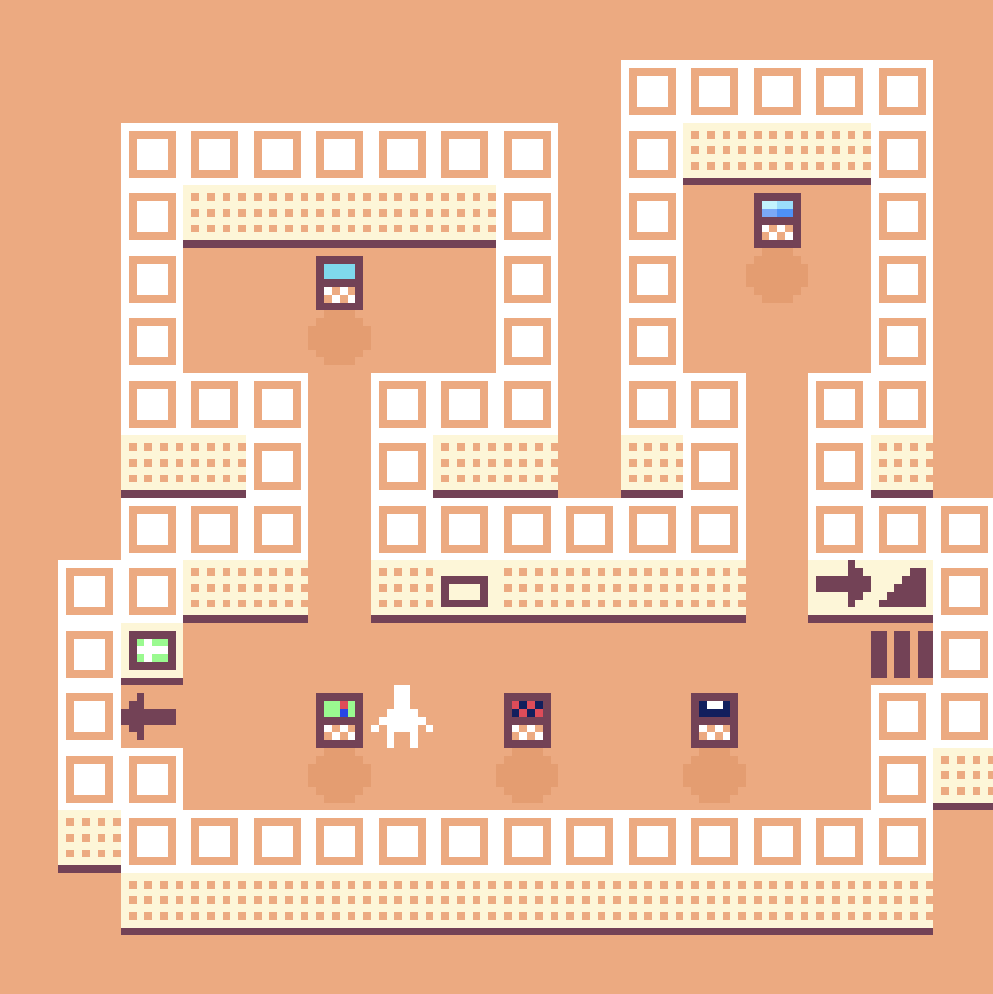

Notably, the discontinuation of the multimedia software Flash in 2020, resulted in many interactive artworks being lost forever. Flash was acquired in 2005 by Adobe Inc., a company notorious for disregarding ethics in favour of financial gain, as in this example, or, most recently with their impossible-to-cancel subscription model and questionable data privacy policy. It is only due to community efforts at preservation like Flashpoint Archive, that going on 200,000 of these works have been preserved so far.

The technological determinism of the Californian Ideology, where the rich “can play at being cyberpunks in a virtual world without having to meet any of their impoverished neighbours,” holds that “it is possible to obtain slave-like labour from inanimate machines. Yet, although technology can store or amplify labour, it can never remove the necessity for humans to invent, build and maintain the machines in the first place. Slave labour cannot be obtained without somebody being enslaved” (Barbrook and Cameron, 1995).

This means it is especially important to preserve new media art that has an interrogative approach to cyberculture, technology, and power relations; where Self-Reference in Web Art “is trying to undermine[…]not its own power to create illusion, but rather the kind of immersion in digital technology that limits our attention to the surface of the computer screen” (Ryan, 2007). At any moment, servers can be shut down, file formats made obsolete, and websites deleted. When archiving files, errors and malicious actors also need to be considered and protected against. Preservation work requires time and resources, and it is not in the interest of capitalist institutions to fund the archiving of ideologically subversive and/or non-profit art.

Flashpoint Archive website homepage, 2024

Guerilla archiving

New media art can be archived in politically hostile conditions by building collections independently of institutions: ‘guerilla archiving’.

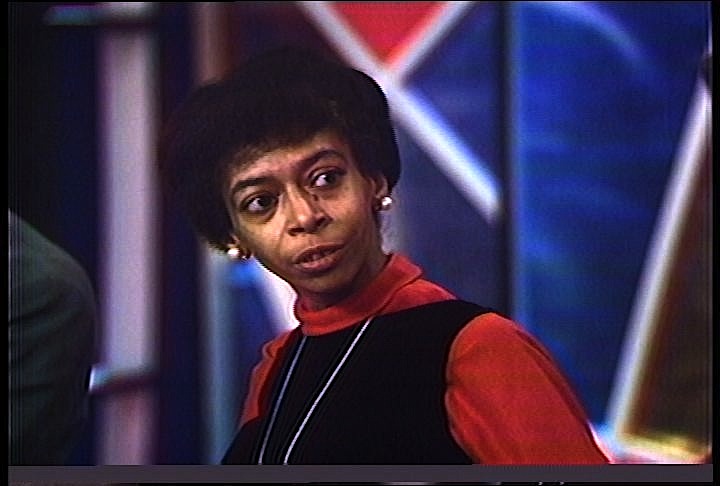

A notable example of guerilla archiving is Marion Stokes’ lifelong dedication to recording live TV, which resulted in a collection of over 400 000 hours of footage preserved on 70 000 VHS tapes. Stokes’ project is “a kind of resistance to an imposed transitory relationship to media consumption, in which nothing is dwelled upon too long or preserved; it’s too expensive. To document and preserve news media (which networks don’t do themselves), outside of an institution, is radical in and of itself” (Hadland, 2020).

Stokes aimed to provide unbiased, free access to information that would transcend the experience of the individual TV viewer. As a group effort with her staff and her family members, she would record several channels simultaneously with the goal of providing people with all available perspectives. After her death, the collection of footage was acquired by The Internet Archive, with plans to digitise it and eventually make it available to the public.

Marion Stokes

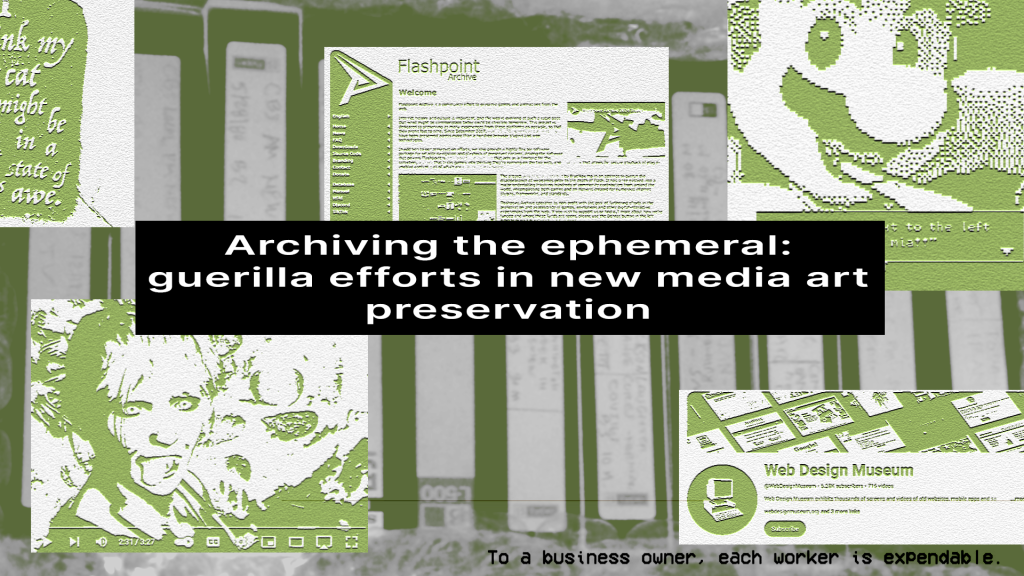

Independent digital museums

The Museum of Screens is a point-and-click experience playable in the browser that documents video games made with deprecated technologies like Flash and Shockwave in the ’90s and 2000s. The museum is a liminal space composed of ASCII art, Windows 95 visuals, chiptune-style music, and free tickets, with a permanent collection of 20 old games. There is also a space for temporary exhibitions. The games are presented through video recordings and written information, with links to playable versions where applicable. According to a manifesto written by its creator, Toulou, the Museum of Screens is a celebration of games “made by people like you and I […] Amateur developers, game enthusiasts, people with little to no experience in the game industry”.

The Museum Of Mid 2000s Forum Signatures is also a browser game. It commemorates the golden age of online forums, stories of broken links, and changing lives of users. In this museum, old forum signatures are brought to life through illustrations accompanied by impressionistic text descriptions written by the game’s creator, Niandra!.

Exhibits include a 404 image captioned “This signature was deleted seven and a half years ago after the user wanted to reinvent themselves and leave their old identity behind,” and a character illustration described as “This signature is of the user’s Original Character, Cecil. Every night, this user would type out at least two pages of crude smutty fanfic without a care in the world about the quality of their writing or how others might find it ‘cringe’. Soon they’ll be thirty and wish they could finish more than one paragraph a week.”

The Museum of Mid 2000s Web Signatures, Niandra!, 2023

The Web Design Museum Youtube channel is a video archive exhibiting over 700 screen recordings of websites and software from the ’90s to the mid-2000s. While the future of Youtube as a platform is unclear, the video format is a considerably future-proof form of documentation and can be compatible with other platforms later on. Some of the exhibits in this collection are the Million Dollar Homepage in 2005 or the The Hampster Dance website in 1999 in Netscape Navigator 4.04. The archiving work performed by the person or people behind this account is especially relevant today, in the mid 2020s, when early 2000s aesthetics like that of the Matinee Sound & Vision flash website in 2000 are revived by the trend cycle; familiarity with the origins of visual aesthetics can help us understand our cultural heritage.

Internet bards

At times, historiography is performed by a person (or people) close to the artist. This is the case with prolific video artist Casina777, best known for the 2011 piece i don’t want my pizza burning. Casina777 uploaded 3D animated videos to Youtube starting in 2008 and can be considered a pioneer of post-internet aesthetic experimentation and grotesque memes.

i don’t want my pizza burning, Casina777, 2011 (as displayed on YouTube in 2024)

In 2023, user cherylfender6386 left a comment under i don’t want my pizza burning, identifying herself as the artist’s sister and sharing the news of her passing: “Hey there this is nurse Cheryl my sister is the creator of this video she did an amazing job she is and was so talented she passed away in 2016…”

A tweet from someone seemingly close to Casina777 corroborates this information: “I lost my love thank you those who enjoyed her animations baby rest in peace love Tom”.

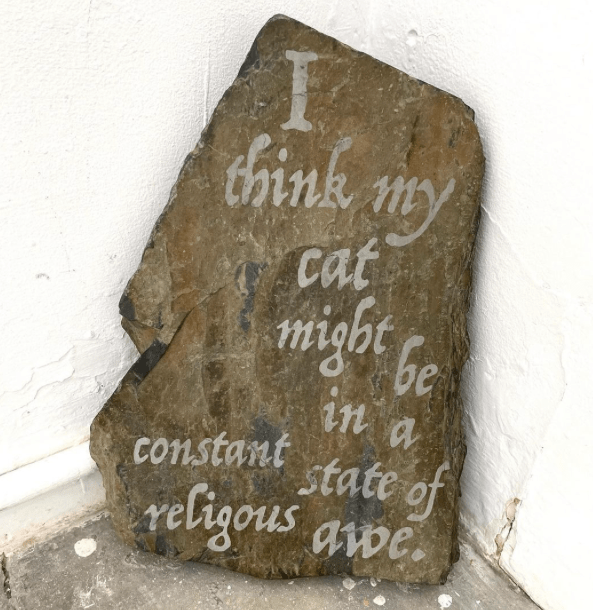

Trystan Williams is an artist who preserves Internet comments by engraving them on found fragments of ceramic and stone. While this artistic practice preserves new media artefacts in a physical format, it notably does not credit the authors of the comments.

Similar to meme pages that source content by aggregating the work of others, Williams’ work gives a further reach and endurance to the comments, but, at the same time, may be read as endorsing the idea of a lone genius artist-curator as the final word in culture, instead of acknowledging cultural production as a group effort.

awe, Trystan Williams, 2024

Knowing when to destroy

While preserving subcultural new media art is important, archives can be tools of oppression themselves. As discussed in the text against the will of game databases, “The will to archive in the ways that most are taught to archive is not an innocent one, it is one of accumulation and the continuation of imperialist and capitalist thought. It is a history of racism and deprivation and destruction and the perfection of history into an art dominated by a handful of countries” (Keeling, 2023).

Adopting an institution-independent archiving approach to new media does not by itself ensure that, for example, private information will not be misused or that history will not be misrepresented. In an age of extreme surveillance, we need to approach our archiving and curation practices with this in mind. At times, radical historiography requires not archiving or even destroying certain media, information, or records of events (metadata attached to pictures taken at protests being just one example). Sometimes, we need to burn our archives.