Effendi Buhing remembers seeing his home, Kinipan, rendered on a map for the first time. Ink black lines on paper marked sacred groves, halted at streams, and curved around ancestral hunting grounds. Neighbours and kin lived in the same forest, but on the map, some were divided into villages, others by revenue blocks.

The 54-year old Tomun Dayak elder speaks quickly, eloquently, only pausing to take long drags from his pipe. Our Jakarta-based interpreter, Ayu Septiari, frequently asks him to slow down. Phrases are lost in the crackle of our internet connection, but Buhing’s anger is palpable.

“We have been here long before Indonesia, the Dutch, we’ve been here for thousands of years. So how could outsiders map our own territory? I would think that we can do it ourselves, so why wasn’t the opportunity to map the land given to us? Why were outsiders given the opportunity to map our own territory?”

The question is rhetorical. Maps became a bone of contention between Kinipan village and the local government after the arrival of palm oil, a lucrative commodity grown in monocrop plantations after clearing hectares of old-growth rainforest.

Deforestation in Kalimantan, Source: Josh Estey/AusAID

Palm oil derivatives like glycerin, propylene glycol, and sodium lauryl sulphate are ubiquitous in our daily lives: toothpaste, ice cream, makeup, and most shelf-stable foods contain palm oil because it is colourless, odourless, and keep products stable across a range of temperatures.

Oil Palm plantation, Source: Irvin Calicut

Kinipan is in Central Kalimantan, the largest chunk of Borneo, an island divided between Indonesia, Malaysia, and the kingdom of Brunei. Spanning more than 500,000 km2 square kilometres, Kalimantan has one of the world’s largest densities of tropical rainforest, orangutans, clouded leopards, and increasingly, palm oil plantations.

Borneo with English names, edit created in 2012, Source: Wikimedia commons user Exagren

Buhing dates the arrival of palm oil company PT Sawit Mandiri Lestari (SML) to 2012. Within a few years, it emerged that PT-SML had acquired a government permit to clear forested land that the Tomun Dayak regarded as their customary territory. To understand how overlaps between Indigenous territory and land designated for commercial revenue extraction came to be, we have to imagine a moment of rupture: once, the forest and the Dayak were the same, and then they weren’t. The forest was assessed and demarcated, a resource that had to be managed for profit. The act of mapping and governance are tightly linked: it is only by committing to paper the location, size, and boundaries of natural resources that extraction can begin.

Community Mapping

With the availability of relatively cheap and easy to assemble handheld GPS devices from the mid-1990s, communities across the world turned to making their own maps. Threatened by pollution, resource extraction, or environmental disasters, communities challenged official maps with maps of their own. Unlike state-sanctioned maps’ emphasis on governance and ownership, community-created maps offer a powerful tool to recenter local relationships with landscapes.

Kinipan’s first community mapping exercise took place in 2017 with technical support from Indonesia’s Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago (Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara, or AMAN).

AMAN logo on banner

Before departing from Kinipan, mappers asked their ancestors permission to map the land in a ritual. Its purpose was “to acknowledge and validate our decisions – that we are taking the right steps,” he explained. Villagers had already discussed and agreed upon which locations would be visited by the mappers, and the ritual ensured both the living and the dead were heard before the land was measured and committed to paper.

The arduous journey being given to male elders, they walked 16,000 hectares of Dayak territory, marking land, rivers, boundaries, and trees on the way. Deep inside the forest, mappers encountered a stake driven into the ground with a PT-SML signboard flagging the proposed plantation concession area.

Deforestation in Kinipan, Source: Save Our Borneo

The community map created by Kinipan elders is still mired in a lengthy verification process at the local government level and ground-level conflict with PT-SML continues. A campaign of intimidation and division is apparent, as seen in the arrests of leaders like Buhing in 2020 and of the recently acquitted village chief William Hengki, all with the alleged aim of prising the Dayak from their land.

Drone Mapping

A drone camera

Coordinates from handheld GPS sets were used to complement indigenous knowledges in the Kinipan participatory mapping process. Around the same time, neighbouring communities in West Kalimantan were using drones to map large swathes of forest impossible to cover on foot alone. Ecologist Irendra Radjawali describes the impact of aerial landscape imagery on communities as “jaw dropping.”

“All of a sudden there are broader pictures of what to preserve and why…these parts of the forest that are super super hard to penetrate because it’s still dense and pristine and then all of a sudden we can see the nest of orangutans and sacred areas preserved by the Dayaks and even they cannot enter this very sacred area but we flew (the drone) over it.”

Nanga Raun, West Kalimantan, Source: Indra Jaya Aswad

But the forests’ vastness was frequently punctuated by stumps or incongruous rows of oil palm. From above, it looked like a monster had chewed off chunks of flesh, gaping wounds in the body of the forest. The deforested earth looked vulnerable, alien even.

Radjawali readily acknowledges that drones are mere tools that temporarily “freeze” the earth into images i.e., maps that can have many after lives – as evidence of indigenous land stewardship over centuries in a court of law or as topographical information overlaid on satellite data for forest governance, to name only two. It is only a formal representation in a world dominated by formal representations. Which is why, the Marind’s efforts to introduce sound into their representations of landscapes is especially poignant.

Sound Mapping

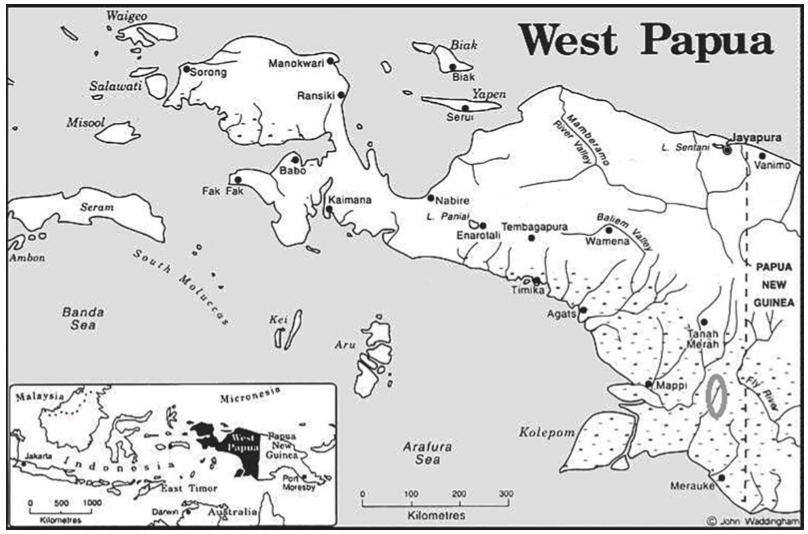

Marind village locations in West Papua, Source: Sophie Chao, John Waddingham & Alan Cline

Almost 5,000 km east of Kalimantan, the Marind live on the South Pacific island of New Guinea. Since the provinces of Papua and West Papua were forcibly integrated into the Indonesian nation state in 1963, the Marind have undergone a violent process of racialized assimilation alongside the expansion of extractive industries into their customary territories. Here, too, maps have emerged as a tool of resistance against government and corporations alike. The only difference is that instead of acceding to the dominance of the visual, the Marind have sought solutions that center their worldview, one premised on the power of sound.

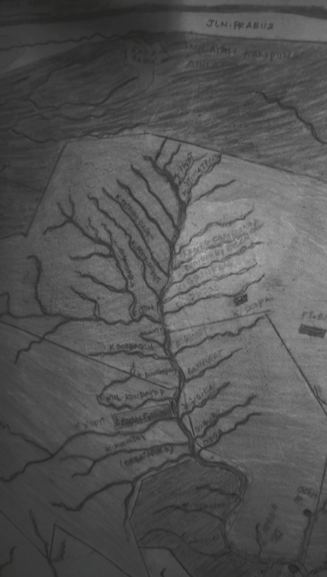

Tributaries of the Bian River mapped by Marind communities, Source: Sophie Chao

Sounds are important to Marind, according to cultural anthropologist Sophie Chao who’s walked and lived alongside the Marind for more than a decade now. Sounds evoke the voices and presences of non-human beings in the forest. These include birds, mammals, cassowaries and reptiles, but also the wind, rivers, streams, thunder and lightning. Chao says,

“Each of these entities…are seen by Marind to be their kin; each of them exists as persons of sorts and each of them have a voice that merits to be mapped and that brings maps to life beyond the sort of 2D visual representation by unfolding in their midst the various sonics of a living and sanctioned forest.”

Maps created by Marind community members are a multi-sensory patchwork. Geospatial coordinates jostle with sound clips of mappers’ laughter, parrots’ squawks, and often, silence. This bioacoustic mapping experiment was meant to assert community rights against the threat of losing forests to oil palm plantations. Yes, Palm oil has made its way to Papua too. But convincing the local government to verify a ‘map of sounds’ has unsurprisingly proved difficult.

The OneMap Project

Indonesia’s massive archipelago-wide mapping exercise OneMap aims to resolve land conflict with data transparency, however, with disputes from organisations like AMAN, it leaves unanswered the question of what kind of data is most representative of a community’s understanding of its land and forest. If the purpose of producing data about land is merely to govern and extract, cartography as we know it has worked well.

But if the purpose of mapping data is to return control and power to the traditional stewards of land, our maps have to become more expansive, and encompass the fullest range of communities’ multi-sensory, multi-species worldviews.

Note: All quotes in this essay are part of interviews conducted by Madhuri Karak for the second season of Data Dialogues, a podcast that brings together multiple perspectives on a single environmental issue. Data Dialogues is produced by the Open Environmental Data Project