Up there, far beyond the night sky, spaceships carrying earthling crews are landing on Mars. Their flight creates patterns of lights; an intricate ballet of technology. Meanwhile, here below in the darkness, the air space in the occupied West Bank and Gaza doesn’t belong to us, Palestinians, while politicians sign deals that further destroy whatever is left of us. Our kites, toy helicopters, and camera drones are all equally dangerous. Forget about launching into outer space — try driving from Bethlehem to Ramallah on any given day. [1]

Pioneers on the Border

“Meet me at the corner of S. Raytheon Parkway and Aerospace Parkway” I text my friend, a planetary geologist who lives in Glasgow. A thread of now-nightly notes about the absurd perversity of the border-military-industrial complex. Leeching into seemingly every sliver of life. The obscenity of occupied Tohono O’odham land–stolen, desecrated, renamed–in the interest of the “stratospheric economy.”

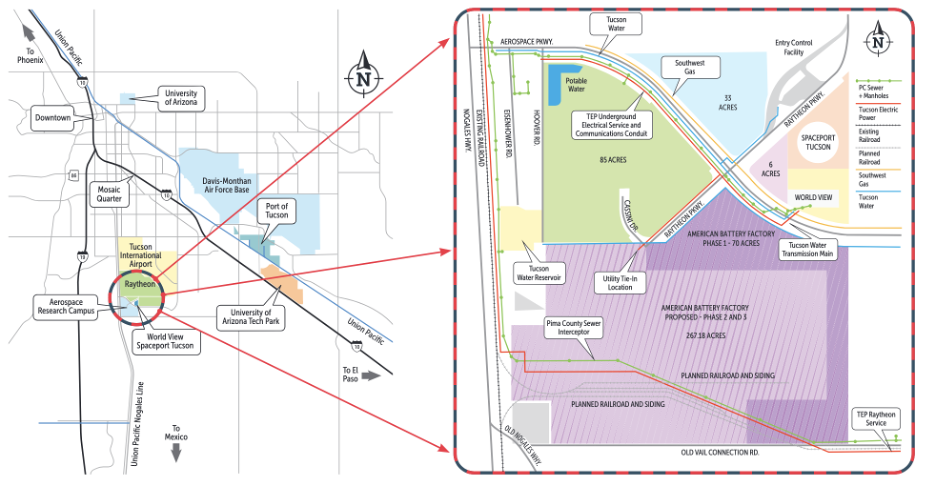

World View Enterprises, a privately-owned aerospace and tourism company founded and incorporated in 2012, manufactures and operates near-space stratospheric balloon flight technology and services. As profiled by TechCrunch: “At World View’s new headquarters in Tucson, Arizona, the paint is barely dry on a gleaming new structure located near the airport, and just down the road from defense contractor Raytheon. The facility, and the site, dominate the landscape, and reflect the enormity of World View’s main goal, which is nothing short of carving out a brand new and unique market for commercial spaceflight operations.” Ostensibly, balloons over the borderlands.

An aerial view of the site in Tucson, Arizona

I’m not going to masquerade here as someone who fully understands remote sensing, or delineations of atmospheric layers. I studied geography, but avoided all things to do with Geographic Information Systems. But I’m a longtime Sonoran Desert dweller and call Tucson, Arizona my home. My home–a 100-year old rented adobe–on Indigenous O’odham land–land that has for centuries been cut, carved, spliced, and paved over at the whims of the settler colonial stakeholder; more recently, transnational corporations such as Caterpillar, Honeywell, Leonardo, Bombardier and Raytheon Missiles & Defense who all have major manufacturing facilities across the city–many alongside the Davis-Monthan Air Force Base… many working in close coordination with the University of Arizona.

In detangling the web of Research & Development schemes and the collusion of companies and universities, in the fabrication and circulation of worlds-ending weaponry that connects this desert with the decimation of Palestine and beyond, I’m also fixating on a borderlessness that binds these regions; shared topographies and morphologies of wadis and arroyos… patterns of resistance and persistence against settler colonial surveillance and its investment in ongoing death.

It makes no difference that my requests to tour the facility were ignored; we could say I’m refused access to the site, but what if I’m refusing to visit?[2]

In previous attempts to access the nearby Raytheon Missiles & Defense grounds, with aims of photographing the company’s desecration of cacti and the fragile desert ecology it’s poisoned for decades, I was stopped in my tracks by the large signage: WARNING UNITED STATES AIR FORCE PROPERTY RESTRICTED PLANT… ALL PERSONNEL AND THE PROPERTY UNDER THEIR CONTROL ARE SUBJECT TO SEARCH…NO PHOTOGRAPHY NO FIREARMS [citing Section 21, Internal Security Act of 1950, 50 US CODE 797].

Nevermind–No firearms allowed at the bomb manufacturing plant. None of us necessarily need be in the building to better understand this architecture of ruination and how the proliferation of so-called “defense” and “aerospace” companies scaffold and reproduce the prolongation of Forever War.

Maybe most striking about World View is how the company amplifies its purported grandiosity; how its “Spaceport Tucson” is “really the only [facility] in the world that has been built for the sole purpose of stratospheric flight;” a launchpad for near-space tourism slated to fly (approx. 23 miles above the Earth’s surface) over the Grand Canyon, the Great Barrier Reef,[3] the Egyptian pyramids and elsewhere–costing passengers $50,000-75,000 per seat.[4] In October 2022, they announced: “[World View] plans to offer leisurely space trips to the edge of Earth’s stratosphere from 2024. Up to eight passengers will float at 100,000 feet… CEO Ryan Hartman tells Axios Phoenix that World View’s tours are more about the scenery and less about the adrenaline.”

This fetishization of the landscape (terrestrial, and beyond) and luxury-baiting serves as flashy distraction from the company’s internal structuring and ambitions. The notion of pioneering is repeated ad nauseam across media materials, operations overviews and leadership biographies (“A world-class team of visionaries with deep experience and expertise pioneering stratospheric exploration and flight”) and is spotlighted on their website: PIONEERS OF THE STRATOSPHERE.

What evidences this “pioneering” ethos? Peeling back the veneers of hollow “sustainability” and “purposeful travel” (as presented on a 2023 SXSW panel), we can understand this near-space exploration as a 21st century iteration of Manifest Destiny; the 19th century bedrock of settler colonial expansionism, exceptionalism and white nationalism across the continent that built on the Doctrine of Discovery. And, as Harsha Walia, quoting Greg Gandin writes, “The history of the US border is one of nearly unimaginable terror and grief, land theft, ethnic cleansing, forced marches, concentrated resettlement, war, torture, and rape.”[5] The World View lust to “pioneer” (conquer) the stratosphere, and beyond, is not dissimilar from the conquest of the southwest and destruction of Indigenous lifeways writ large:

[The] formation of the US–Mexico border through the historic entanglements of war and expansion into Mexico, frontier fascism and Indigenous genocide, enslavement and control of Black people, and the racialized exclusion and expulsion of those deemed undesirable. The US–Mexico border must be understood not only as a racist weapon to exclude migrants and refugees, but as foundationally organized through, and hence inseparable from, imperialist expansion, Indigenous elimination, and anti-Black enslavement. US–Mexico border rule intersects with global and domestic forms of warfare, positioned as a linchpin in the concurrent processes of expansion, elimination, and enslavement, thus solidifying the white settler power of racial exclusion and migrant expulsion.[6]

Granted, World View is not explicitly implicated in the same vigilantism and genocidal acts of erasure and replacement in the same sense as, say, the Ku Klux Klan (whose recruits formed the US Border Patrols’ first generation of agents, ca. 1924). But we can draw through-lines of bordering with similar patterns of the dispossession of Indigenous and racialized communities across the region–the occupation of these sites in the interest of capitalist gains, and reinscription of the landscape to serve imperial agendas. Afterall, the World View campus–as part of the “Pima County Aerospace Research Campus”–occupies over 400 acres of Tohono O’odham land swindled from its Indigenous stewards during the Gadsden Purchase (1853-1854). We will not be deceived into thinking word choice is unintentional; “pioneering”, specifically across Arizona (see also: the “Territorial Period” 1848-1912), is expanding the legacy of colonial missions and settlements, seizing desert land–framed as “barren,” terra nullius, and making it “bloom” for industrial agriculture and unsustainable subdevelopment sprawl.

Today, the pioneer wears a polo shirt. And appeasing shareholders is their divine decree. As example, current President and CEO Ryan Hartman joined World View in 2019 after previously holding the same roles for Insitu.[7] The World View board chair, Dennis Muilenburg, is former Boeing Chairman and CEO and currently the CEO of New Vista Capital, a strategic advisory, venture and private equity firm set on “transforming aerospace and national security.”[8]

Pima County Aerospace Research Campus, 2023 footprint (courtesy Sun Corridor, Inc.)

The Profits of War

A two-minute promotional video produced by World View features a hearty dose of stock images and footage, narrated by an Attenborough-in-training. Windfall verbiage promises “new perspectives” for “a radically improved future” – vacuous nothings couching quite a bit. That overcoming “the world’s toughest challenges” and “safeguarding critical infrastructure” must be understood as dog whistles for armament–be it as data mining, biometrics, bomb-making, or other colonial containments and methods of obliteration. That “stratospheric solutions” aka “high-resolution electro-optical, infrared, radar, hyperspectral and other remote sensing capabilities can deliver a wealth of insights across a range of applications,” build on the Department of Defense’s (DOD) global surveillance strategies and global circuits of bordering and carceral capture:

World View, a global leader in stratospheric exploration and flight, announces the successful opening and initial funding of a Series D round… The Series D raise in funding specifically supports the increasing demand for high-altitude intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities identified by the U.S. Army, U.S. Air Force, U.S. Department of Defense, and global defense forces, as well as growing demand for commercial remote sensing solutions. With this combined strategic investment, World View is poised to execute a robust flight manifest over the next 24 months, further developing and improving its flight systems and capabilities.[9]

This intertwining of stratospheric “exploration” and DOD-led warfare speaks to what Felicity Amaya Schaeffer, drawing from Kristen Simmons, emphasizes as settler atmospherics; that “there is an everyday feel of warfare on the [Tohono] O’odham reservation, where helicopters, drones, the Border Patrol, and ground and air sensors occupy the reservation from the sky to land.”[10]Granted, if we’re to insist on borderlessness as elemental to liberation, this necessitates understanding all of the Sonoran Desert as occupied land, while negating the reservationization reproduced by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and Dawes Act. Centering, as Natalie Diaz reminds us, how “[we] either need to move completely back and find a language before empire, or we need to leap forward and imagine a language beyond empire.”

How much violence does this ongoing “exploration” hold? What are the implications for the human and more-than-human on this planet and beyond, if “space tourism” is just cover for military proliferation?

Border Balloons

In this respect World View–as a singular company–fades into the abyss of myriad tech-startups and NGOs/“aid” organizations and shell companies, most either founded by or colluding with stakeholders (shareholders) in defense contracting.

We follow balloons, emulate how they drift over walls–dance past any demarcation’s deceit. In the social sciences, a “follow the thing” methodology is utilized to track the commodity trail of goods and services as they move through the highly fraught research, development, manufacture and trade routes of late capitalism’s bowels. But for most, these globalized networks of labor/resource exploitation have lost shock value–we know that many links in the chain are fraught with violence, deception and corruption…we just actively choose not to see it, let alone act towards its repair.

Alison Hulme writes:

The call to follow-the-thing created by the combination of Harvey, Marcus, and Appadurai in that earlier era of globalisation, could now in the era of high globalisation, perhaps be usefully added to by a call to better know the unfollowable thing – the gaps, the mechanisms of the chain that cause them, and the collateral damage they incur, in the name of capitalistic ‘success’. Rupture is so frequently now the norm, a ‘flow’ of micro-catastrophes at each part of the chain, that serve to make it stronger but polarise the lives of those along its trajectory. The questions to ask are: Why can’t we follow this thing? Where are the ruptures that stop us and what is behind them? What don’t we know about this commodity chain? What can’t we seem to find out and why? Where does the chain disappear to? [11]

The purpose, here, is not to follow around surveillance balloons–like Project Genetrix, Custom and Border Patrol’s tethered aerostat radar system (TARS), the Pentagon’s “Covert Long Dwell Stratospheric Architecture” (COLD STAR), or the Israeli Occupation Force’s (IOF) high-altitude missile defense aerostat (developed by Israel Missile Defense Organization (IMDO) and the US Missile Defense Agency) per se, or even the ways World View has pilfered[12] Tohono O’odham land (Pima County) with unconstitutional subsidies–plundering and poisoning air and sky (and of course, aquifers… soils, subsoils…).

More it’s following the ways we can evidence The Border’s elasticity; never just an international boundary or singular line of steel bollard and barbed wire–but an always-shifting set of relations often obfuscated by logistics, contracts and their verbiage, “About Us” pages and board member bios; the fine print (or redacted print, or manipulative misnomers) behind “defense” companies whose operations grease the cogs of the hyper-surveillance and militarization machines of war. As Fady Joudah writes, “Then they came for the desert, but the desert, like the sea, didn’t quench their thirst.”

In this contemplation, our ‘unfollowable’ thing is a balloon–and how we read it as it sways and rises in a breeze, to conjure its freedom once released from its bouquet, or from the clenched fist of someone attempting to keep it contained.

Great March of Return, Gaza (April 10, 2018, courtesy Mohammed Zaanoun/ActiveStills)

Balloons for Returning Home

The World View balloons “[use] helium, which is nonflammable and nonexplosive, rather than hydrogen, which other space tourism companies use.” To consider the helium balloon–its weightlessness, its fugitivity, its borderlessness–is to understand and necessitate expansive liberation… a freedom of flight and gestures towards unimpeded movement–the freedom to tunnel into soil, to dance among clouds, to return.

How does a helium tank enter Gaza, Palestine amidst the illegal ongoing, worlds-ending besiegement by the IOF? How does the helium defy the Wassenaar Arrangement control lists, or the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories’ (COGAT) “Order regarding Monitoring of Security Exports (Controlled Dual Use Equipment Transported into Areas under Palestinian Civilian Authority) 5768-2008″ (amended March 4, 2015) which stipulates the materials that cannot be brought into Gaza without specific permitting? Lists of ever-changing prohibitions/restrictions as far-reaching, absurd, and severely consequential as to include items such as: epoxy resin, all varieties of gravel, asphalt, lumber beams and boards more than 2 cm thick, ginger, chocolate, wheelchairs, A4 paper, crayons, hearing aid batteries, lentils, tomato paste, matches, thread, steel cables of any width.

A detailed two-year investigation by Al Mezan Center for Human Rights (March 2018-March 2020) earmarks that “the Israeli military repeatedly deviated from the fundamental rules and Israel’s obligations under international law. This unlawful conduct resulted in the death of 217 Palestinian protesters, journalists and medics—including children and people with disability—who were killed during the reporting period.”

The Return, a weekly mass mobilization across Gaza (beginning Land Day, March 30, 2018) to approach (attempt to breach) the IOF’s border, activated Palestinians in Gaza from six demonstration base sites: Al-Shoka, Rafah; Khuza’a, Khan Younis; Al Bureij refugee camp, Middle Gaza; Al-Zaitoun, Gaza City; Jabalia refugee camp, and Beit Lahia in North Gaza. These predominantly peaceful protests were oppressed with routine brute force by the IOF; occupation soldiers used live ammunition, tear/CS gas, rubber-coated metal bullets and a full cache of assault weapons against participating Palestinians, and their land, indiscriminately. Those seeking an end to the siege, an end to all borders, a return to their ancestral homeland were maimed, massacred.

Most mesmerizing from the Sonoran Desert where I watched closely by phone was witnessing the spectrum of spectacle, of possibility, on display each week. Return, or what should be as ordinary and welcome as going home, a seemingly impossible feat when up against the savage and barbaric occupier and their walls. Costumes, flags, face paint, confetti, balloons. Nakba survivors, newborn babies, and everyone in between paraded, danced, ate, sang, slingshotted, dodged poison canisters, lit tires, shared slogans, showed us–all–an otherwise to…a more than… the Zionist capture of land and time. And while phosphorus frequently obscured the sky and these gestures towards liberation were ferociously targeted, new horizons were brazenly displayed.

Great March of Return, Gaza (January 4, 2019, courtesy Mohammed Zaanoun/ActiveStills)

Who decides a balloon’s intent? Who criminalizes the air? Where should we go after the last frontiers? Where should the birds fly after the last sky? [13] Balloons defying border walls, balloons threatening, defeating, nuclear superpowers

Ahmed Abu Artema, a writer, researcher and one of the co-organizers of the Great Return March wrote for The Electronic Intifada (August 25, 2020), “Better to launch balloons than die in silence.” In the essay reflecting on the colonized’s obligation to resist (and in this case, launch “incendiary balloons” to disrupt the IOF’s atrocities), he describes:

In recent weeks, the tension between Palestinians in Gaza and Israel’s forces of occupation has increased. Israel has used the launching of incendiary balloons by Palestinian youths as a pretext to bomb Gaza once again. The release of the balloons is a gesture of protest against how the Israeli occupation has procrastinated in abiding by its previous agreements with the Palestinian resistance. Under those agreements, Israel had committed to easing the siege on Gaza… The Israeli military has responded to the incendiary balloons by carrying out dozens of raids on sites used by Palestinian resistance fighters with US-made F-16 jets.

He furthers:

If one wishes to understand why incendiary balloons have been launched from Gaza, it is crucial to go back to the circumstances under which Palestinian youths feel compelled to act. I have been asked repeatedly by many Western journalists if the youth who launch incendiary balloons are contradicting the principles of the Great March of Return, unarmed protests which began in 2018… That offers some explanation as to the motives of people releasing balloons. The balloons are crossing the boundary and reaching towns and villages that have been stolen from Palestinians. They are being flown as a protest against the theft of our homeland.

Throughout 2021, we witnessed the spark of the Unity Intifada–an uprising standing on the shoulders of the First and Second Intifadas, spread across Palestine and its diaspora. Hunger for upheaval and revolution carries through to today–including the global Student Intifada mobilized to end this genocide and insist on divestment from deathmaking. The above image, of Israeli occupation police officers seizing balloons in Sheikh Jarrah, Occupied Jerusalem, shared by professor Refaat Alareer, poet of the words ‘If I Must Die’, is born of this moment.

Writer Mohammed El-Kurd contextualized the Unity Intifada; his Sheikh Jarrah family home, as ground zero:

This year, “decades happened” indeed. Last summer’s revolution proved that the symbolic meaning of borders doesn’t extend beyond the material fact of their cement. Palestinians everywhere rose up against ethnic cleansing & colonial violence. It was a beautiful moment of unity. Palestinians stormed past the police barricades preventing their entry to their capital. Revolutionaries dug an escape tunnel under an “impenetrable” prison. And, despite legal fragmentation and arbitrary barriers, hundreds of thousands of protestors chanted for liberation.

In Sheikh Jarrah, Silwan, Beita, Um El-Fahem, Gaza, Masafer Yatta, Nazareth, Haifa, and in exile, cement was just cement. It didn’t translate into control or sovereignty. Then again, in reality, the weight of that cement is crushing; the fragmentation it imposes is very real. Uprisings are costly. Thousands of stomping soldiers performed the spectacle of “restoring governance” in our communities, appeasing an Israeli audience suffering a devastating shift in global opinion. And today, despite the progressing rhetoric, our reality is the same. 300+ Palestinians were killed & martyred by the IOF this year; thousands remain inside Zionist prisons. Countless homes were demolished & thousands face imminent dispossession. Millions of us remain besieged, occupied, or dreaming of abandoning the camps to return home.

Years ago, my mother routinely “smuggled” meat & eggs from Bethlehem beneath her car seat on the way back to Jerusalem. We used to wait at the checkpoint for hours, furious as soldiers searched us, anxious that they might find the banned goods & force us to pay a fine. But when I look back on those memories, I remember the meals my mother made a lot more vividly than I remember the fear and fury. She was able to disregard the Wall and checkpoints and bring Bethlehem home. And so she taught me the dignity of negating cement. I don’t tell that story to minimize the real & material violence Palestinians face daily or the organizational and institutional challenges we must address. I share it to say: as long as we have dignity & self-respect we will continue to struggle for our liberation. Onwards.

Repellent Fence, Land art installation and community engagement (Earth, cinder block, para-cord, pvc spheres, helium), 2015. Installation view, US/Mexico Border, Douglas, Arizona / Agua Prieta, Sonora (Courtesy Postcommodity)

Moving Through and Against

A few years prior to the Unity Intifada, in 2015, the “Postcommodity” interdisciplinary art collective launched 26 large balloons across the US/Mexico border, across O’odham land, to not only bring international attention to the area’s longstanding crisis of mobility, but to encourage artistic and civic collaboration between those in Douglas, Arizona and Agua Prieta, Sonora, and beyond.

From their project’s description:

The Repellent Fence is a social collaborative project among individuals, communities, institutional organizations, publics, and sovereigns that culminates with the establishment of a large-scale temporary monument located near Douglas, Arizona and Agua Prieta, Sonora. This [two] mile long ephemeral land-art installation is comprised of 26 tethered balloons, that are each 10 feet in diameter, and float 100 feet above the desert landscape. The balloons that comprise Repellent Fence are enlarged replicas of an ineffective bird repellent product. Coincidentally, these balloons use Indigenous medicine colors and iconography—the same graphic used by indigenous peoples from South America to Canada for thousands of years. The purpose of this monument is to bi-directionally reach across the U.S./Mexico border as a suture that stitches the peoples of the Americas together—symbolically demonstrating the interconnectedness of the Western Hemisphere by recognizing the land, Indigenous peoples, history, relationships, movement and communication.

We can again envision this air as a breach, as moving through and against borders; its patterns–and, its illegibility to repressive powers who are too ignorant to hold sacred a bloom’s scent in the breeze; “…Postcommodity activated local social networks to legally transfer helium, a HAZMAT (hazardous material) necessary to fill the balloons, across a national border although customs agents on both sides said it would be impossible.” [14] While these tethered balloons are emblematic of the tension at institutionalized points of entry and across the weaponized desert landscape–the gesture of their installation reminds us of our shared air, of how bodies and beings will always be on the move–will always be in defiance of walls, borders, and settler colonial strictures. Postcommodity insisted, “For four days, the line of monumental balloons became a beacon for the historical stewards of the land, and those who are following ancient Indigenous trade routes in search of economic opportunity.”

Repellent Fence, 2015 (courtesy antiAtlas of Borders/Postcommodity)

From Palestine to Sonora, we see Indigenous self-determination as the foremost charge, answer, to settler colonial conquest. As potentially small an act in the face of belligerent behemoths, these material gestures of passing through, floating over walls, lend ways forward– border balloons defying capture, and, the task of capturing.

I suppose a question, then, is how we soar, when up against seemingly insurmountable surveillance? How we emulate this weightlessness, as we, and the land, shoulder the remarkable weight of grief, rage, resentment, and melancholy. And how we toggle the desire for being tethered, or rooted, with the life-affirming need to move

Footnotes:

[1] Karim Kattan, “Let Them Take Mars,” (January 28, 2021), +972 Magazine, https://www.972mag.com/let-them-take-mars/.

[2] This is inspired by a conversation with religion and global migration studies scholar Barbara Sostaita, who, while contemplating sacred vs. profane mobility across the Sonoran Desert, reminded me of Audra Simpson’s discussions of refusal. See: Simpson, Audra. “On Ethnographic Refusal: Indigeneity, ‘voice’ and Colonial Citizenship.” Junctures: The Journal for Thematic Dialogue, no. 9 (2007): 67–80.

[3] From May 15, 2024: “The Victorian [Australia] government has invested $37 million from its Breakthrough Victoria venture capital fund in a US satellite imagery and space tourism company [World View]… The investment represents the fund’s biggest bet and came via an announcement made just days before Victorian Treasurer Tim Pallas released the state budget.”

[4] In my research, I’ve yet to find evidence of completed touristic flights, despite approx. 1,000 tickets sold (as of May 7, 2022) for “for flights to the edge of space as early as 2024.” As they self-promulgate: “World View is now the most sought-after space tourism operator in the world, with the longest waiting list of all companies, according to its statement.”

[5] Walia, Harsha. Border and Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism. Haymarket Books, 2021. P. 19

[6] Ibid. p. 21.

[7] Insitu is a wholly owned subsidiary of The Boeing Company headquartered in Bingen, Washington that specializes in unmanned aerial systems (UAS, UAVs), payloads and software used by NATO forces, the US military, the Brazilian Navy and other global militaries; as they tout: We pioneer autonomous systems to positively impact people’s lives and change the course of history.

[8] Noteworthy, a member of their “team” includes Yotam Avrahami–Intelligent and Green transportation lead commercial and PPP programs at Deloitte–who was profiled by The New York Times (October 7, 2023), Y Net, and elsewhere: “”It’s the thought that you have friends that will be in immediate danger, and you cannot help them,” Avrahami said. “You’re trying to protect them [Israeli family]. It’s as simple as that.” Avrahami purchased a one-way ticket to Israel for more than $2,000. He said his wife was concerned for his safety, but “she understands the necessity.” Avrahami sent out dozens of emails to notify clients he would not be available for the foreseeable future.”

[9] “World View Secures Strategic Series D Funding Led by SNC,” World View, February 27, 2024, https://www.worldview.space/stories/world-view-secures-strategic-series-d-funding-led-by-snc.

[10] Schaeffer, Felicity Amaya. Unsettled Borders: The Militarized Science of Surveillance on Sacred Indigenous Land, 2022. P. 60.

[11] Hulme, A. (2017). Following the (unfollowable) thing: methodological considerations in the era of high globalisation. Cultural Geographies, 24(1), 157–160. P. 159. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26168798.

[12] In a January 10, 2023 Arizona Public Media piece: “World View CEO Ryan Hartman admitted the company is not yet profitable. “Our revenues don’t fully cover the expenses of the business, which is normal for an early growth stage business. On a yearly basis we’re clearly cash flow positive because we exist,” Hartman said, explaining that the company continues to attract investors. Supervisor Steve Christy doesn’t want the county backing a business that appears to be struggling. “All of the indications with [World View] sends a shiver up my spine. It doesn’t feel secure, it doesn’t feel right, it’s, I think, very shaky,” Christy said.”

[13] From Mahmoud Darwish’s “The earth is closing on us, pushing us through the last passage”; Wrote Edward Said: “Since Darwish left Beirut in 1982, one of the main topoi in his verse is not just the place and time of ending (for which the various Palestinian exoduses are an all too persistent reference) but what happens after the ending, what it is like to live past one’s time and place, how survival after the aftermath becomes an esoteric and certainly an exotic situation for the poet and his people. “The earth is closing on us, pushing us through the last passage,” he wrote in 1984: We saw the faces of these who’ll throw our children Out of the windows of this last space: Our star will hang up mirrors. Where should we go after the last frontiers? Where should the birds fly after the last sky?” Said, Edward W. “On Mahmoud Darwish.” Grand Street, no. 48 (1994): 112–15. https://doi.org/10.2307/25007730.

[14] Irwin, Matthew. 2017. “Suturing the Borderlands: Postcommodity and Indigenous Presence on the U.S.-Mexico Border.” InVisible Culture, no. 26 (May). https://doi.org/10.47761/494a02f6.b3918149.