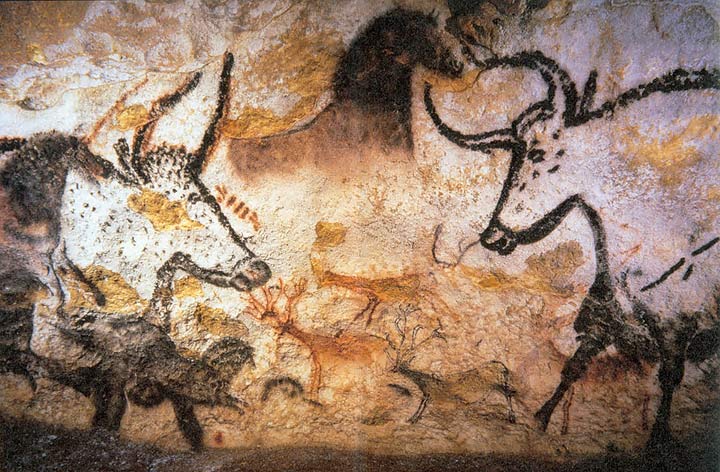

In 1940 a cave at Lascaux, in South-West France, was discovered containing almost two thousand paintings and etchings from around twenty-thousand years in the past. A majestic and expansive vault of prehistoric art, Lascaux is one of the oldest examples we have of human creative ancestry. Exhibiting at Bristol Museum in 2023, The Cave Art of Lascaux: A Virtual Reality Experience promises a chance to explore that famed site and see the inside of the cave for yourself.

Prehistoric Art at Lascaux Cave

Attempts to recreate the experience of visiting Lascaux have been in the works since people shared the very first images of it, and this has become an essential aspect of the cave’s existence after it was closed to public access in 1963. Hidden for all that time, visits by people over just twenty years put the artworks in danger of decay and damage due to human curiosity.

Lascaux International Center For Parietal Art

At the site near Montignac today is the International Center of Parietal Art, a museum containing a full scale replication of the underground site. Opened in 2016 and housed in a modern centre of preservation, it was built as an extension to older recreations existing already. The VR experience, like other digital renderings of the cave, such as that on France’s National Archaeological Museum website, is built on scans and 3D maps made at the centre, and is touring multiple sites.

A Virtual Reality Experience

The exhibition at Bristol Museum is a ticketed and timed tour of the 3D replication, guided via VR headset. You enter the gated display via public information boards about Lascaux, into an exhibition of static pieces of relevance to the cave. These standing exhibits range from part of the cave recreation, to figures representing the early modern human creators of Lascaux, to touchscreens with interactive explorations of specific details. This all leads to the virtual reality space, a hall of squares in which people stand to experience the tour.

The Cave Art of Lascaux: A Virtual Reality Experience, Bristol Museum, 2023

When it comes to the main attraction you are set up with a headset by a reception desk assistant, who takes you through using a non-wired VR headset, all of which are displayed like bowling shoes in racks behind them.

You then experience a fifteen minute immersive tour of the cave, with a guided narration and interactable moments. In the various rooms of the cave you are guided to look to the most impressive and interesting of the artworks as they have been preserved and rendered.

For what it is worth this is an enlightening experience if like myself you had no idea of the sheer scale of Lascaux. In another sense, there is the aspect of it being a clunky way to immerse you in this history, which I couldn’t ignore throughout. It reminded me of being like a magic trick that you have to convince yourself was impressive. I came out of the virtual reality exhibition more interested in the static displays than what I had seemingly been paying for.

The Cave Art of Lascaux: A Virtual Reality Experience, Bristol Museum, 2023

To comment on the experience, my gripes might come off as small at first. When the headset placed me into an oddly lit 3D space, made of scanned models with cut off black areas of void at the edges, I was disappointed to see that the experience was clearly on the lower capacity for modern 3D technology. Rather than being wowed, it deflated the experience to be able to easily see the seams between rooms, and to see the screen tearing of the high polygon scan models as I moved my head around.

When I thought of what it was I was being shown however, the level of history, I let myself actually take in the space and it became much more impressive to consider these works of ancient people, and exciting to be inside the space.

The Cave Art of Lascaux: A Virtual Reality Experience, Bristol Museum, 2023

The tour guide aspect felt arbitrary, distracting from that wonder, with a fifteen minute time limit to explore a space that represents and holds so much, it all felt short, rushed and interrupted by the inclusion of interactive moments I suppose are meant to appeal to children, but are unfortunately poorly signposted.

I want to establish that in the past I’d been fully bought in on the idea of VR history tours, even writing in 2018, a so called “manifesto” for the creation of VR history experiences after putting myself into my overdraft buying an Oculus Rift headset. I don’t know if I’d stand by what I said there today.

Virtual Solutions and Real Problems

Virtual Reality is seemingly solving a problem here. There can only be replications of Lascaux and when those are held at the site itself, there is a major inaccessibility to travelling to a town out of the way for most people. This is especially true with the current economic crisis and gradually worsening ability to visit France facing the average person in the UK. However, the delivery of the export of this vital culture via VR is something I will question.

Aside from my general disappointment at the tour’s quality, it was the more imminent issues with the design of this experience that made me question its effectiveness.

Photography at Lascaux, by JoJan, CC BY 4.0

A good deal of help for instance was needed from the exhibition assistants on guiding people with the headsets on through the interactive moments of the tour.

The first basic interactive hurdle was with language settings, which I experienced alongside the visitor in the space next to mine, as we both adjusted the headsets. As the selection of language is made by directing your head as the app starts up, we both selected Italian, which was dead-centre, without realising we were doing so, and had to be guided through restarting the experience.

The fact we would have been listening in Italian would also have been clear to anyone else in the room too, since you can hear the tours being given by other headsets the whole time. Having a sensory processing problem this was a familiar experience to me, but counts against any kind of illusion of total immersion.

There are two moments where you need to blow, which the sensors in the headset will only detect if you blow strongly, and was the moment where myself and other users needed to be coaxed out of our anxiety. However, considering the way in which the spread of microbes is an issue to us, it still felt wrong.

Photography at Lascaux, by JoJan, CC BY 4.0

A more fundamentally off-kilter aspect was that the way the VR was calibrated meant the edges of the experience were very close to virtual boundaries set up to make me aware of when I was exiting my square. I would reach out a hand or step towards a wall, guided by the narrator and have everything be intercut with a blue wireframe turning red at the point of exit. This meant that I was constantly just hedging back and forth trying not to leave the square as I followed the instructions.

Even more important, in terms of the curation of history, is a problem with the tour’s racialised representation of you, the visitor. Inside the VR I was given white skinned hands, which is accurate to my body, however, if that is the experience of all visitors, that is an issue. Even if this was because you are given hands based on the hand tracking’s approximation of your race, it’s an issue. The automatic visual racing of the visitor’s body by a technology, either passively or actively, counts to impose assumption. If the lowest effort of these types of racialised experience is true, as I suspect, it means designers didn’t even consider that kind of thing and used whiteness as a standard.

The experience then by design is exclusive, makes choices to exclude and foreclose on visitor identity. In another sense, as the website warns, visitors with epilepsy are advised against taking part in VR. While disability access is mentioned and featured as a thing to contact the Museum about before visiting, as ever, the concerns of those with epilepsy, in experiencing a historical monument that need not feature exclusion, are excluded.

A Cave Recreation on Display at Lascaux

All of these are things you can imagine happening with any other technology, a failure to acknowledge how things are going to actually work when people get into a space and start finding all the things you didn’t think about. There is a kind of disappointment however when it is the supposed cutting edge of technology that gives you a less interesting and more exclusionary experience than seeing a piece of painted recreation there in tactile space.

A History of Virtual Reality at Lascaux

This isn’t the only VR experience of Lascaux that exists today, or that has existed in the past.

There is for instance a different, forty-five minute tour of the cave that exists, housed in Paris’ Cite de l’architecture et du Patrimone which can be taken by groups of up to six, and utilises a much larger exploration space, in order to replicate the actual physical experience of the cave’s interior. It is seemingly targeted more towards academics seeking to explore the site. Is this more what I’d had in mind when I’d booked the ticket?

The idea of a virtual reality vision of Lascaux, and of a VR exhibition being the future is not new though. During the 1990s the artist Benjamin Britton created a virtual reality exhibition of the cave that he began work on in 1991, made with the assistance of the people at Lascaux. In 1995, Botton presented the presented the tour of Lascaux at ISEA: Sixth International Symposium on Electronic Art in Montreal and the exhibit toured widely. From images of the contents of the experience, you can see that, in terms of the graphical fidelity and the technology employed, there is not the vast kind of difference that thirty years of advancement might suggest. The tour is displayed via a headset similar in build to the Meta Quest, although wired, and the caves are rendered with images of the recreations layered on top of 3D models.

LASCAUX, Ben Britton, 1991-1997

This is, perhaps, you can say, an indication of why I am sceptical of VR exhibitions being touted as revolutionary. All that has truly improved is the fidelity and interactivity of this experience, and not to a level you might expect considering innovation in other computer arts spaces, including video-game VR too. While access to VR technology is on a non-specialist consumer level now, there is a level of recycled excitement about ideas in public exhibitions that are still hindered by basic accessibility and inclusion issues.

LASCAUX on display, Ben Britton, 1991-1997

A Vision of the Future?

What concerns me most is the potential for the continuation and expansion of things like racial exclusion and disability exclusion in the public exhibition space via these “new” technologies, when these are already so ingrained in life. New spots for erasure emerge if these concerns aren’t integrated from the start, and unfortunately as a technology itself VR currently already leaves a lot of people with bodies not imagined by developers out of the ideal imagined experience.

In Pursuit of Repetitive Beats (2021). Installation view at FACT Liverpool. Photography by Mark McNulty

If a future of history experiences and museum exhibitions lies with Virtual Reality, it has to happen in a way that is openly honest about the nature of what is being promised. I find this Instagram introduction by artist Darren Emerson at FACT, to his acclaimed experience In Pursuit of Repetitive Beats (showing there in early 2023), explaining visually the specifics of the experience, and how to interact with it, to be an example of this kind of frankness about what VR offers, how it does it, and for whom.

Otherwise, if considerations of public accessibility aren’t taken, we’re kidding ourselves out of a way to experience and present something as important as Lascaux digitally and physically in a way that is actually available to the world to which it belongs