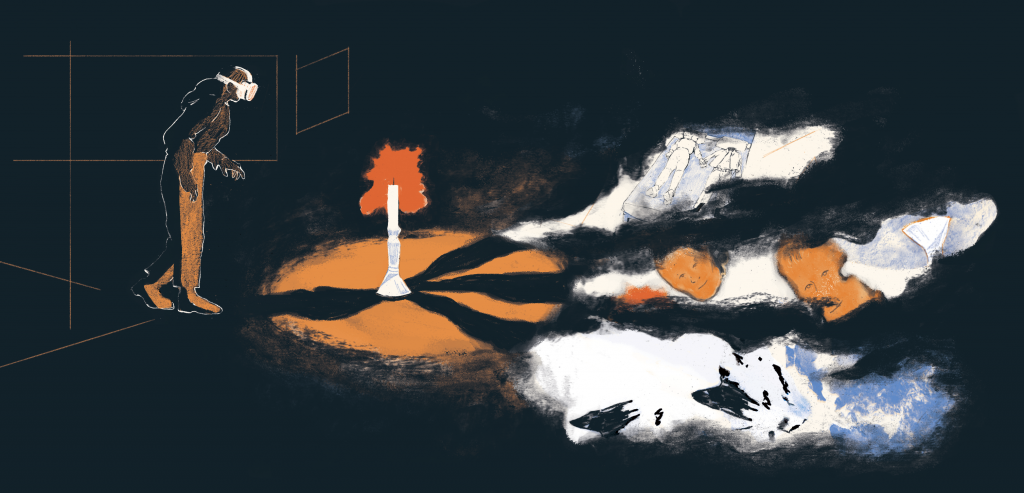

Grief is one of the most painful human experiences a person undergoes during their lifetime. If you are lucky enough to find people to love, then you are also unfortunate enough to experience agonising loss. To many, virtual reality (VR), when combined with concepts of grief, is an opportunity to escape from the unbearable reality into a fiction where the person who has died can be resurrected. VR is, after all, a carefully designed environment in which anything is possible, and where one can conjure what is not there; what has been lost.

Illustrations by Lucy Haslam

But can this technology, by reflecting a deeper truth through fiction, help those most unable to move on? VR, along with a host of other technologies that augment what we experience through our senses, make up the category of ‘mixed reality’ technologies’. Its use is far from one-dimensional. Like books or movies, VR is a mode that people use to tell themselves stories. These stories are the underlying structures that form our emotional lives. Our minds create characters and relationships with the people we interact with, helping us understand ourselves and our purpose in the world. Fundamentally, what happens with the death of a loved one is that an important relationship is traumatically severed and we reel from the loss of something precious that partly formed who we are and how we see ourselves.

Therapeutic Simulacrums

Many people are capable of transitioning to the stage where the pain is tolerable. But others struggle to create new meanings and long desperately for the reality before the pain, unable to fully internalise the change.

“The person has a problem with accepting that the person is no longer with them, and sometimes does a lot of things to keep contact or preserve the relationship in the way that it once was,” Professor Rosa Banõs observes.

Dr Banõs, from the University of Valencia, has been studying how VR can treat pathological grief and other mental conditions that stem from intense trauma such as post-traumatic stress disorder. She’s observed the multitude of ways people reject loss. Some even going so far as to ‘mummify’ parts of their house – maintaining the pristine state it was in before the person’s death. Others avoid the subject entirely.

The subjectivity of the grief experience means that the use of therapeutic VR is not prescriptive, Dr Banõs says. Patients work closely with their therapists to create custom simulations that work through the roots of their entangled traumas and conflicts.

And unlike what some may mistake, often these simulations do not seek to create avatars of the person that the patient has lost, though that can be useful in cases of unresolved interpersonal conflicts. Instead, the therapy works on the level of more abstract symbols, metaphors and narratives.

Dr Banõs uses the ‘Book of Life’, a virtual book created by Banõs and her research team that allows people to reflect on different moments in their lives. Patients envision their loss as a chapter in a book they can progress from. They are invited to celebrate and grapple with the emotions of their severed relationship by memorialising them in the VR book. Whilst in the simulation, patients have the opportunity to be incredibly active – choosing photographs, audio files and video clips to put into their Book of Life. By engaging in this creation and editing process, patients can begin to understand their grief in the framework of a new story.

“In this way, it’s conventional therapy,” Dr Banōs says. VR is a natural extension of therapies that ask patients to use their imagination or look at pictures or keep a diary. Being able to be more immersed in the act may simply make it easier to engage in a constructive inner monologue.

Grief Rituals in Virtual Reality

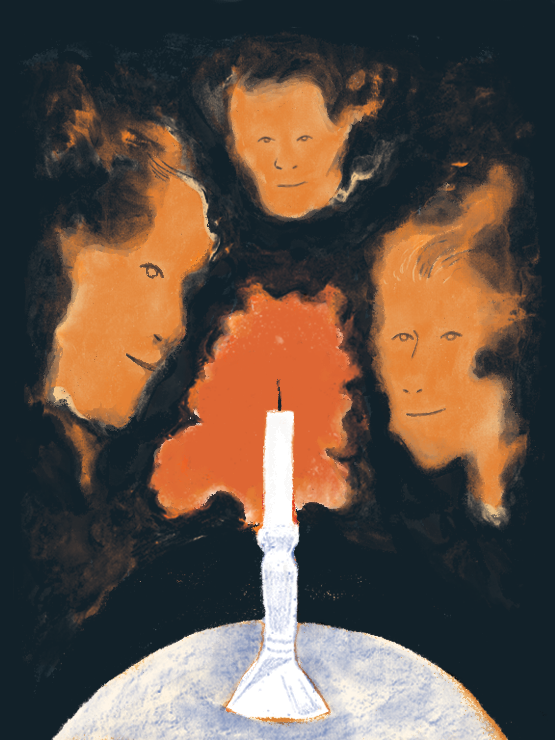

Crossover is a strange VR experience made by Kent Bye and his team. Kent Bye currently works as a podcaster and journalist who covers VR and, in 2015, he co-wrote and produced Crossover. The user is in a house with five other people, depicted as floating heads in different rooms. The roof is gone and above is a night sky. As the user walks between the different rooms, they can hear conversations happening between characters, who are mostly ghosts that are unable to ‘cross over’. They talk about memories they shared, questions they never asked, and messages they never managed to pass on.

At the end, the user is in one room with all the characters, sitting around a table lit by a candle. After finding peace through dialogue with each other, the characters unburden themselves from the painful stasis of grief and disappear upwards into the sky until the story’s sole living character, Andrew, is left.

Andrew takes after Kent’s own life and experience. In 2014, Kent’s wife died by suicide, seven years after her father took his own life. He found that it was often difficult to express his wife’s life beyond its sorrowful end.

“This was a way to abstractly speak about the love and beauty in our relationship, and the connection we had,” Kent says.

The entire VR experience is surreal and operates through a dream logic. The core fabric of the experience is emotional: visceral, but sometimes inconcise and fluctuating. Through it, you can see many of intimate reflections of Kent’s grief process. He says: “In the process of writing it and making it, it was a deeply cathartic release of being able to imagine conversations that never happened.”

Kent says that, in some sense, we tell ourselves conscious and unconscious stories all the time to understand our lives. Crossover is a story of Kent and Jennifer.

The last to leave Andrew in Crossover is his wife, Leah.

Leah: “Until we meet again. Maybe next time it won’t have to end this way.”

Andrew: “I know, I know. This isn’t our last time. Have a good journey. May you continue to do your work on the other side.”

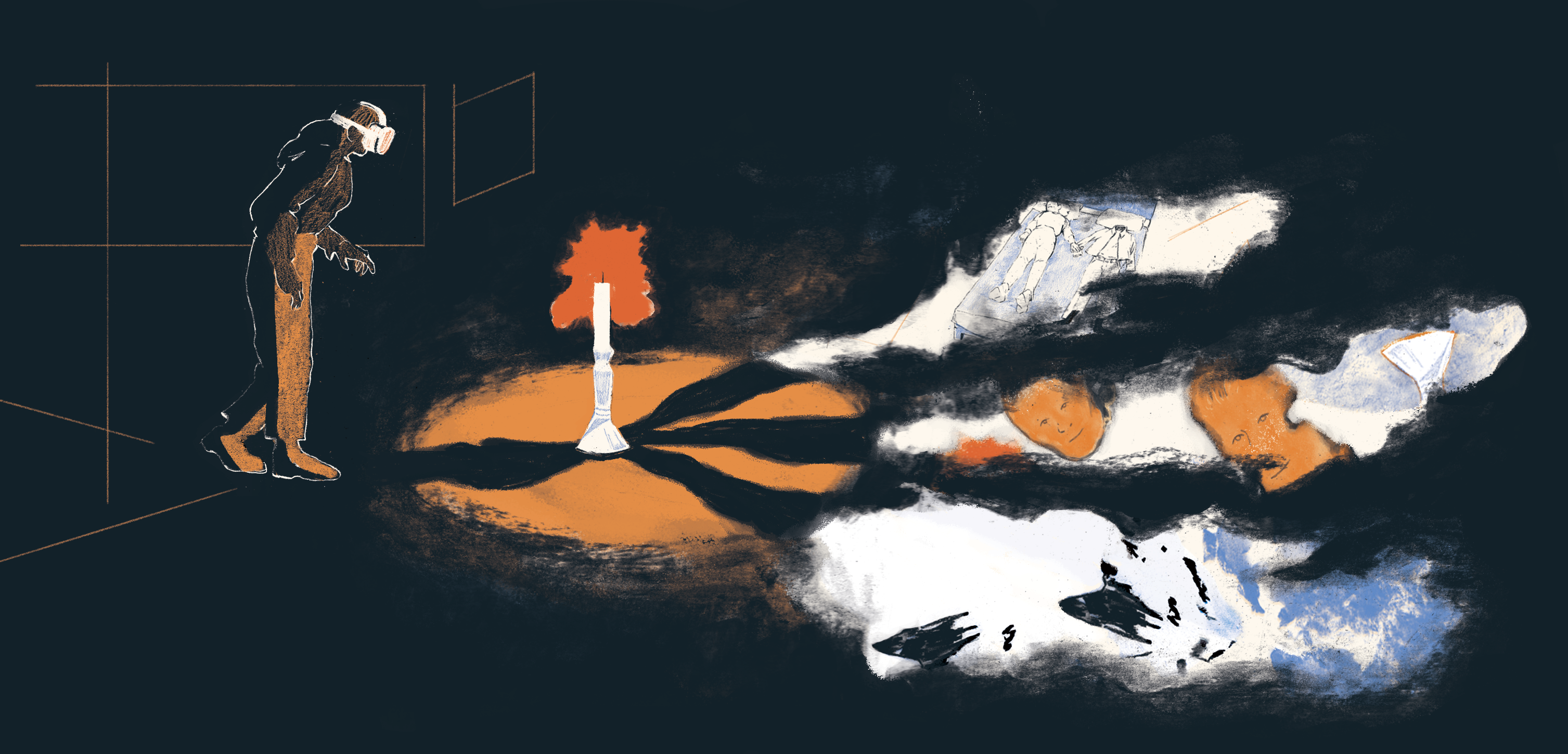

Third Party Authorship

With increasing access to the technology that underpins it, the commercialisation of curated VR simulations is a growing possibility. Some companies, such as Kaleida – the company responsible for resurrecting Kim Kardashian’s father in a hologram – already specialise in using synthetic reality technologies to revive celebrities, politicians and other historical figures.

Other companies, like Vive Studios in South Korea, have made headlines by bringing a grieving mother’s child ‘back to life’ in a VR simulation. Her child would call out to her while running around a play area and stand still while her mother stroked her cheek.

A very intuitive point can be made about the lack of therapeutic purpose in avatars that do not catalyse their recipient moving on. The resurrections that aim to simply recreate situations where the bereaved can interact with an image of their loved one are, mostly, benign. In extreme situations, an emotional dependency on this escapist fantasy can form – but then again, they can form when a bereaved person escapes into their dreams, a photo, or just their imagination.

The crucial difference in the Kaleida and Vive Studios examples is that the creation process is surrendered to others. The conversations or messages that occur between the grieving and the grieved are imagined, at least partially, by a third party, with incentives that extend beyond the patient’s healing. These incentives include profit, and could incidentally entrench the state of grief by creating non-therapeutic products.

A third party will never fully grasp the complexities of a relationship between two people, as experienced by the person who has suffered the loss. If a VR simulation does not appropriately reflect the bereaved’s reality, it may erase it or cause further distress. “There does seem to be a boundary,” Kent Bye says, “where you’re not only speaking on somebody’s behalf, you’re potentially overriding someone’s memories.”

A few years ago, I lost my brother to a meth addiction. It was, to me, an abrupt and violent end to a man who I saw as ambitious and kind but endlessly tormented by the weight of his own demons. After his death, I lived a life that was rendered harsh, sharp and thin. There were protracted periods of time where I would lie in bed with his clothes laid out in the shape of a person next to me. I would hear his voice when walking down long and empty hallways at night. And I would often go to bed and dream of a different life – one where he was not gone. It destroyed me to know that he would no longer exist as an ‘other’; that he could only exist in my selfish memories and thoughts.

If there is something that I am grateful for during that time of my life, it is that I could re-discover a relationship with my brother after his death (even if it was just with the portion of him that existed as an extension of my mind). It is often said grief is work. It is in many ways: individuals must drive themselves to seek new ways of being. VR, if it is to be constructive, is a tool to assist with that labour. It will not be effective if it is the means by which we deny or outsource it.