What follows is a nonlinear series of logs where logs shift meaning across the forest and the computational. Fecund with ecologies of life crossing natural-digital continuums, the log speaks of: fallen trees cut into logs in the forest, logging into a digital platform online and logging thoughts while researching slime molds, algorithms and non-extractive artistic research practices.

In these logs reflections on a month spent logging reflections about searching for slime molds in the forest near Rupert Residency in Vilnius, Lithuania. Researching how to become students of slime molds while thinking alongside them in the context of algorithmic studies.

Logs get rained on, just like me

Today it rained so hard outside. I wondered if slime molds around us were soaking in each drop, ready to come out, ‘will they be easier to find if it’s just rained?’

A friend misunderstood slime molds and thought I meant slugs. The slugs do love the rain, sliding easily on wet grounds. On the way to the grocery there are seemingly hundreds of them on the pathway. Something crunches under my companion’s boot – we hope it’s only a twig.

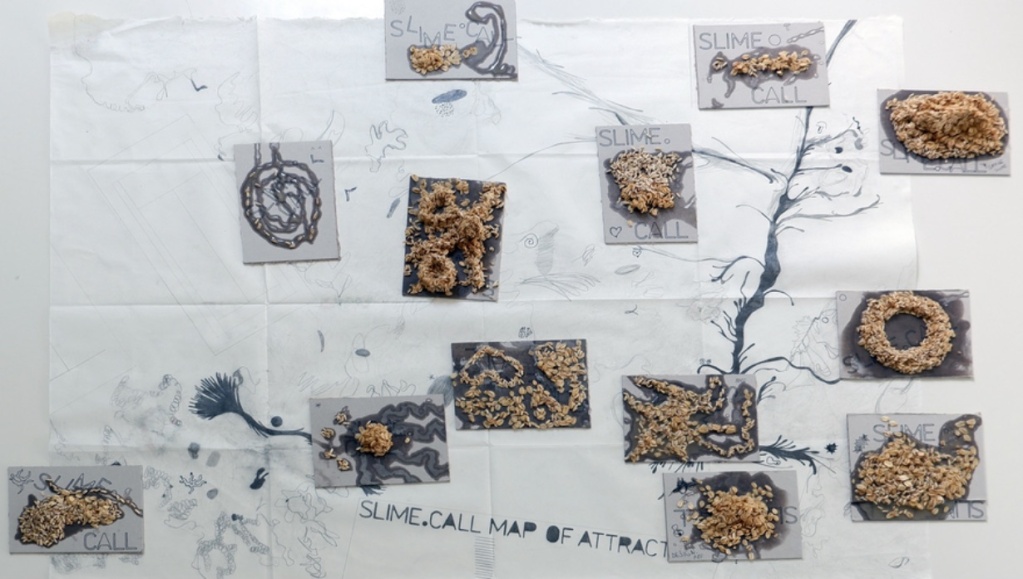

As we have been walking through the forest visiting our SLIME.CALL cards every day, parts of the forest have begun to take on nicknames: ‘the indentation’, ‘the one near the bell shaped mold’, ‘the one near the mushrooms that had bloomed’, ‘the one near the cafe’, ‘ the one in the indentation behind the tennis courts’ – through repetition and trying out various ways of naming our pathways, we sense deeper into the SLIME.CALL, searching for our slimy teachers.

Yesterday we found slime molds for the first time, I had suggested that we take a different path through to the same card. By following another path, it led us to a seemingly magic log. This log is a home for different kinds of slime molds – in various visible states – dormant, active, about to become active – plus moss and mushrooms. It was like the boredom of the regular route brought us to a new route where everything could be found anew. Reflecting on repetition: it’s easy to get stuck in a same and same again, and when it breaks, this is where possibility can be found.

Finding the slime mold felt really joyful. The kind of unexpected and totally overwhelming feeling of – it’s you – when that particular you – you hadn’t been anticipating to actually find. Somatically, I felt bubbly in my stomach, and kind of giggly. I also felt relieved, like it was a gift to meet this slime, and aware of the networks I’d been traipsing over daily to get here.

Logging into Non-Extractive Research Practice

Today, we… collected neighbors? Brought friends from the outside, inside to be our Mitbewohners? Something more than a roommate something less than a lover. Sitting in the dark in our closet, bits of moistened rotting debris: twigs, wood, leaves. Maybe they will grow slime molds, maybe they will continue to rot. We are a temporary we, the we of me – in the studio – and the rotting, wet, woody closet companions I care for this month.

This afternoon, in conversation with a friend, we spoke about slime. I relayed concerns about extraction and spoke about observation – a practice that does no harm. Though is that true? Are there any artistic research practices that do no harm? Observation, certainly is not neutral – who views who?

I’ve been struck in researching that slime molds are always used for something in scientific and artistic research. They become metaphors to be taken up and used, their performances are determined to mean something. In this month we are rather wondering, how can we become students of slime molds?

Becoming students of slime molds – means so far to move slower, lower, smaller and less grand. Slime molds move slowly and only visibly flourish when the time is right – a lesson. They can lay dormant for years, awaiting the right conditions.

In Heavy Processing Jas Rault & T.L. Cowan speak about the white settler relationship to research where one “gets it, curates it and shares it” without connecting to historical or situated context. They continue that heavy processed methods call for specificity and considerations that invite community processes into the work that is being done.

Researching slime online everything is sped up and enlarged, shifting time and scales of visibility. To be students of slime molds would be perhaps to come back to some idea of ‘real time’, to allow for fuzzy image quality and to look carefully, rather than through enlarging.

In Leanne Betasamoke Simpson’s, “Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation”, Simpson re-tells her version of a traditional Michi Saagiig Nishnabeeg story of how maple syrup was discovered. In the story a child gathering firewood in the forest, stops to watch a squirrel. Seeing how the squirrel suckled on the tree, she too placed a tobacco leaf in front of the tree expressing gratitude and then copied the squirrel suckling from its branch, tasting the sweet sap. Simpson remarks “It’s one of my favorites because nothing violent happens in it.”

After bringing my roommates into the closet, I lit a candle for them, to thank whatever decomposing they want to share with me. Appreciating them for their context, I hope there will be slime on them, and that slime will wish to show itself to us – and – if it doesn’t, that is still great, other things are also there to learn. Unlearning seeing as knowing is a practice of this work.

Thinking about research practices that are non-extractive from Heavy Processing, they move from TMI (too much information) to NEI (never enough information). To become students of slime molds, is to be inhabiting the space of NEI. Slowing down enough to open up the space for becoming students of slime molds, is to support an unexpected process across beings that might have a lot to teach us – if only we enter into relations with them that do not continue to make them into metaphors.

Logging into a world of slime

What about learning about slimes by embodying their way of being? To be students of slime molds we want to try to understand their way of being, and perform a ritual of calling them forth, learn with algorithms.

Algorithms are simple descriptions of processes designed to achieve specific tasks. They are used in mathematical calculations and they are the basis of modern computing. An algorithm is a bit like a recipe: it has the desired output of a specific dish, it has the input of specific ingredients, and it describes how to output a dish, from the input ingredients, in a sequence of specific steps. A question is: how can algorithmic procedures invoke slime mold intelligence?

Slime molds (in Lithuanian: “Gleivainiai”) are ancient – the oldest known fossil of slime mold encased in amber is dated at 100 million years. They dwell in forests and feast on rotting plant material and their name comes from the fact that they look like a slimy blob of mold when they are in their plasmodium stage. At said stage, these ancient ancestors, in their plasmodium stage, are single-celled organisms: physarum polycephalum in Latin, which literally means multi-headed physarum, referring to its multiple nuclei in a single cell – while physarum means a small bellow (“dumplės” in Lithuanian), probably referring to the way the slime mold moves by expanding and contracting.

At the first glance, they might look like a fungus or mold, however at different stages in their life they act both like a fungus and like an animal. Therefore they have been called mycozoa – mushroom-creatures (in Lithuanian: “grybagyviai”). They are at the boundary of classification, confidently defying it: they are not a plant, not an animal, they switch between liquid and solid forms, changing their shape to move around.

Slime molds are intelligent but not in human ways. They sense their environment through what is called chemotaxis and mechanotaxis and make decisions about which direction to grow. Slime molds have been shown to be able to find the shortest path through the maze or the most optimal distribution of nutrients across different food sources. Because of that, they have been used for the algorithmic modeling of optimization tasks, inspiring digital slime mold algorithms, and for modeling efficient and resilient transport systems in cities.

It’s a limit of the imagination to think of slime molds as only making vibrations and moves in the world that are disconnected from other beings.

The Log of Slime on a Log

At the beginning of our SLIME.CALL walk today I felt a bit hopeless, thinking to myself ‘If we found slime mold would we even know to do?’.

So much of our month has been feeling about not seeing, not finding, not knowing if we would connect to slime molds and also not feeling the need (on my part) to determine how and if we would come to find them in the end. I mean, it could have been that we would have kept calling again and again and again, walking on a compost pile and seeing nothing.

But then, after traipsing through the forest and getting bitten by mosquitos and attempting to let the ants do their thing. There it was, my companion called me ‘Ren! Ren! It’s here!!’ and indeed, there they were. Little cute pink dots on a log. The log was not too covered with lichen or moss, but not entirely new either, just beginning its moment of decomposition. There they are composting and decomposing their little selves, these brilliant more-than-human ancient ancestors.

I love how they can transform state, how they can pop up and hide away, how they can appear to us as little pink dots. It feels like once we started seeing slime mold, maybe it had been there everywhere all along: our process of walking through the woods, had been only the reality of getting attuned to the forest, sinking deeper into seeing and feeling the woods that we could then find them, even though they’ve been there under our noses doing their work and minding their business, us not able to see them yet because we hadn’t tuned into their frequency. A lower slower calmer less rushed reality. Oh it’s so exciting to find them, and now, that we have…. what do we do?

For now we left some oats for them, hoping to feed them, and we said a little articulation of appreciation for them upon leaving, thanking them for gracing us with their presence. We did the same for the ants too – as we passed what I think is the biggest ant hill I have ever seen when we walked back to another calling card.

Tuning into the forest, there is so very much to see, sense and be with.

Stacking logs for the Planthroprocene

In Jane Prophet & Helen V. Pritchard’s edited volume, Plants by Numbers — they speak about the Planthroprocene — rather than the Anthropocene. This helped me to make a conceptual jump – being students of slime molds is actually what we all are, plant life makes the world possible for us, not the other way around. Connecting to our ancient plant elders, our non-taxonimic multispecies ancestors.

In their chapter on Computing Diatoms, Pritchard writes about the politics that emerge in more-than-human interactions. They speak about the hierarchies of communication and intelligibility that are placed onto more-than-human interactions where communicability is based up on taking up the language of those in power, citing Franz Fanon (1967), and continuing with the impossibilities of unmaking colonial or imperial worldviews through using a dominant language, citing Ashcroft (2001). I found resonances with taking up Pritchard’s praxis of a ‘world feeling computing’ which engages the world, as they write “in a different way, a recognition of more-than-human creativity beyond modes of inclusion or communicability”. Questioning my desire for my slimy companions to perform anything, even for me to be able to see them, is one of the biggest re-framings of the SLIME.CALL, which this log brings me to.

Getting into sensing the world by just attempting to understand how slime molds sense it prompts me to change my practices to get closer, there is so much to learn as students of this beautiful organism.

Log on, hide in a log, logging into to other movements

The reality is one of pushing forward and retrieving/receding back – the way that slime molds move. This also feels like a description of movement we have been working with during this residency. Whether we want to or not, there is a push forward, an action or an attempt in one direction and then something that pulls us back – whether that be the literal weather, or emotionality, or life beyond the residency, and then another push – a kind of seeking and searching out that pushes us to try a new thing, cover a different surface with our interest and gaze, to take more photographs and seek more with the magnifying glass.

Yesterday afternoon we went to visit our sculptural attractant SLIME.CALL cards. To wonder what had munched them, hoping to find slime mold. These sculptural attractants full of oats and honey, things slime molds like to eat have been guiding us through the forest, giving us a path to consider where to look. We placed these sculptural attractants at sites that looked alive, moist, woody and covered from view. Not random, and also not free from bugs, insects, life, mycelial and ant networks all throughout the forest. A very different set of calculations than I have made when moving through any landscape before.

On a forest walk, I usually move with purpose, looking up at the trees, and out ahead of me – up and out. In our SLIME.CALL walking, I am walking crouching down, closer to the ground. We found the calls are mostly decaying, holes here and there where they have been eaten: a lot of decomposition and not a lot of finding. Noting to myself while following our slime path I remarked, “Western science leads us to believe that seeing is believing – what happens when you can’t see it because you can’t find it?”

Computing infrastructure is all around us, just as slime molds are too, just because we can’t see it or find it, doesn’t mean they are not there.

The slime molds are gone again. Back into the logs from whence they came. It felt a bit sad today to go into the forest, wanting to greet our teachers, and finding that they decided to retreat again.

With gratitude to my slimy algorithmic research companion, Goda Klumbytė, everyone at Rupert Residency July 2024 & most of all to our slimy ancestors that wetly greeted us – thank you