While strides have been made in recent years, there remains a significant gap in the representation of black characters in video games. Often even with representation, black characters are stereotypical and/or lacking depth.

Eddy Gordo from the popular fighting game franchise Tekken is one such example. Apart from Eddy’s cool, Afro-Brazilian aesthetic, little is done within the frame of the video game series to explore the character and the political dimensions of his fighting style, capoeira.

This reflects the wider issue of representation in games and poses a serious challenge to video game developers to make characters whose political motivations are part of their representational assemblage. This would constitute more meaningful, more political play, harnessed through critical game design.

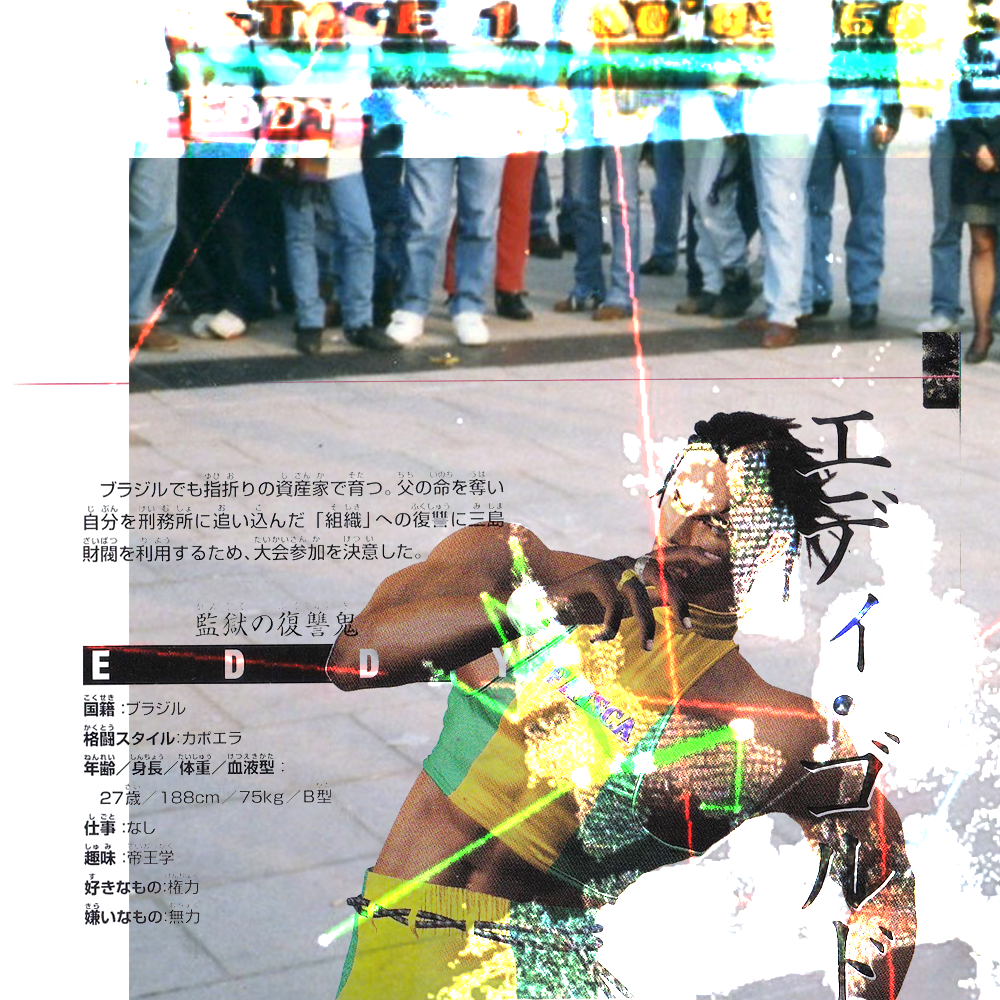

Eddy Gordo introduction screen, Tekken 3, Konami, 1997

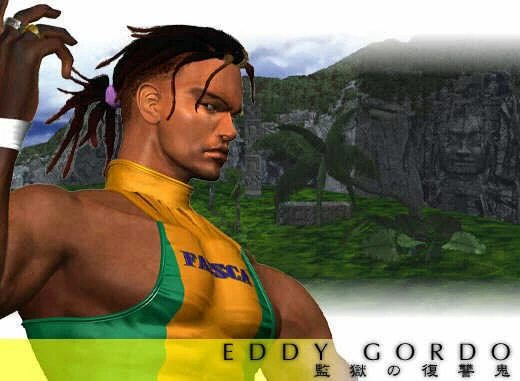

Eddy Gordo is one of Tekken’s most iconic characters. Introduced in Tekken 3 (1997), his flashy moves and acrobatic, capoeira combat style have made him a fan favorite. However, his character is often reduced to these physical traits, without much depth or attention given to the cultural and historical significance of capoeira.

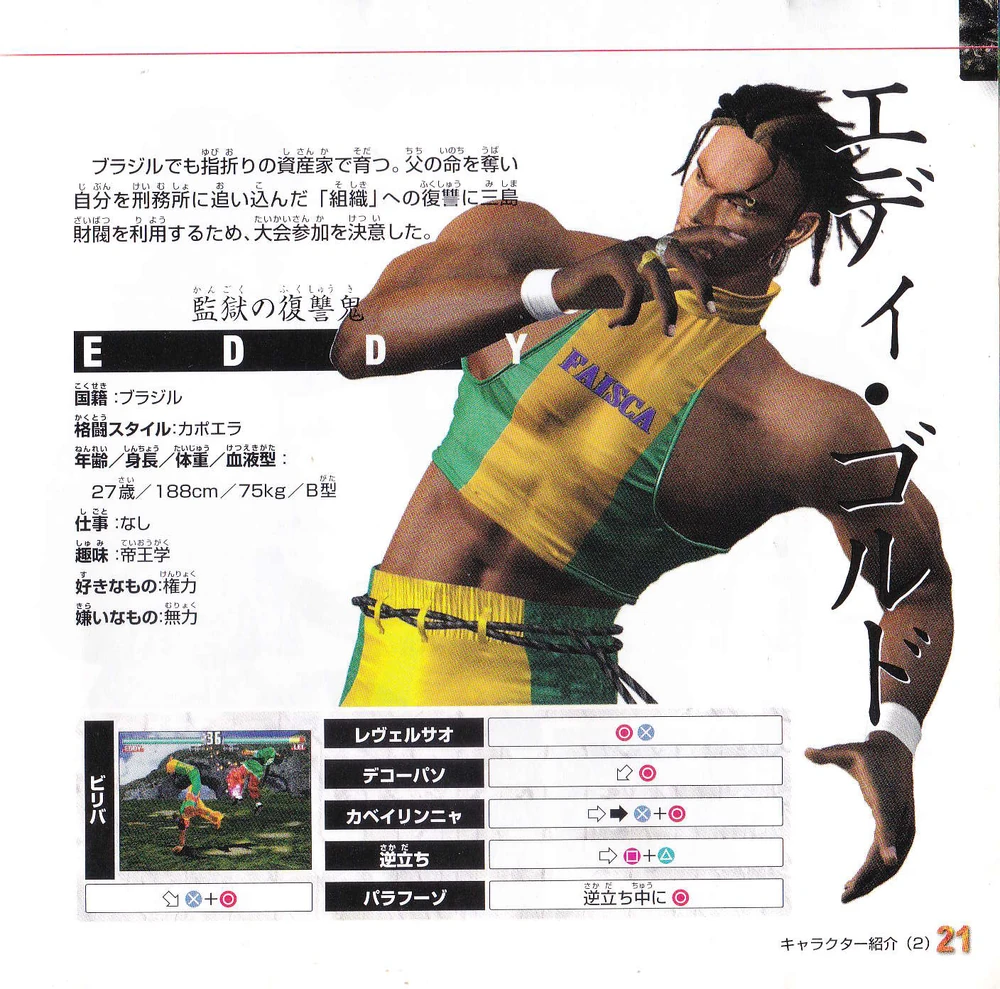

His storyline—a revenge arc against corrupt forces that have wronged him and his family—could be the plot of almost any fighting game character, and does little to engage with the broader sociopolitical context of Brazil, especially the African diaspora and the legacy of colonialism. Additionally, Eddy’s character in the Tekken roster is often criticized as a “button masher”, a term used to describe a character seen as uninteresting and too easy to play because they can be powerfully utilised by seemingly random button presses.

Eddy Gordo exemplifies how video games, like other media, perpetuate colonial-era tropes by reducing complex cultures into marketable, surface-level symbols. What if you could rework or re-master Eddy Gordo into something that truly honors the anti-slavery and anti-colonial roots of capoeira?

Eddy Gordo page in the Tekken 3 Original Manual, Konami, 1997

Eddy was created by Japanese game designer Masahiro Kimoto from the Tekken design team. Look at the ‘international’ roster of Tekken 3, and you can see aspects of a tapestry of sense-making about national and racial relations coming out of Japan’s fighting game market in the second half of the 20th century. This is a mode of design featured in other successful franchises like Street Fighter, and can be seen throughout global ‘competitive sports’ entertainment media as an enduring memetic of the era.

Tekken 3, Konami, 1997

Capoeira is a martial art that developed among enslaved Africans in Brazil as a form of resistance against colonial rule and oppression. It is not merely a fighting style but a cultural practice intertwined with music, ritual, and community. Eddy’s original portrayal in Tekken detaches Capoeira from its historical roots, transforming it into a flashy, marketable spectacle while overlooking the fact that it was born out of the struggle for survival and freedom in the face of systemic brutality.

This detachment reflects the broader colonial tendency to appropriate and commodify racialised cultures for entertainment without engaging with their deeper significance. Media theorist Lisa Nakamura aptly calls this type of digital minstrelsy, “race play”. Any attempt to rework Eddy’s character to a more culturally relevant form would need to contend with the divisions within Capoeira.

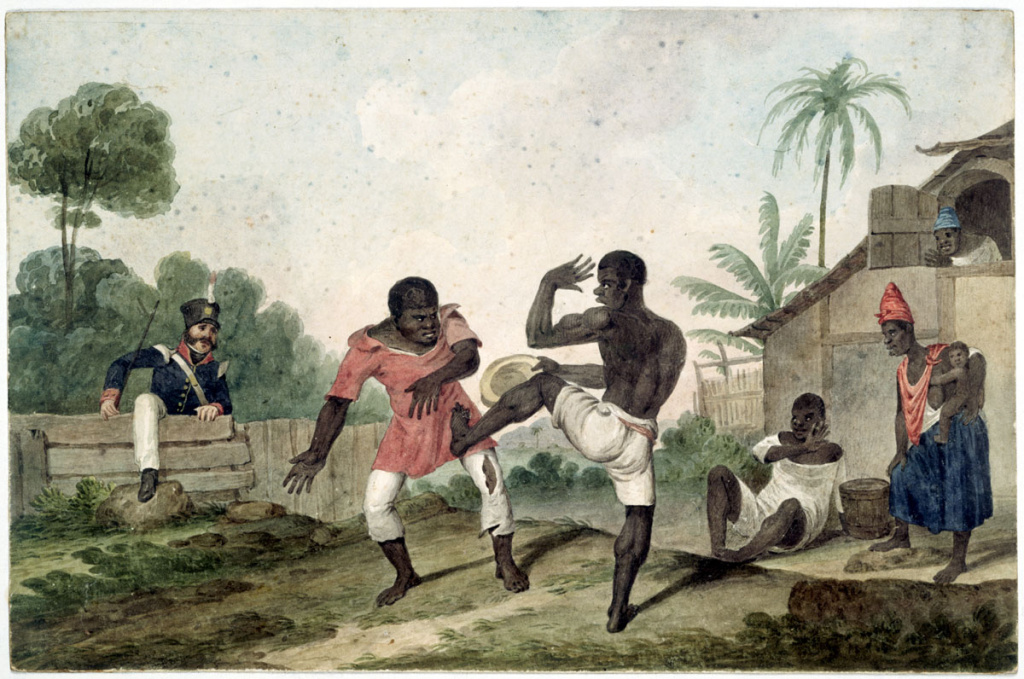

Negroes fighting, Augustus Earle, c. 1824 (Painting depicting an illegal capoeira-like game in Rio de Janeiro)

Capoeira is usually divided into two groups, the one more formalized, commercial sport called Capoeira Regional, and the one more cultural variant called Capoeira de Angola. Capoeira de Angola is a traditional form of capoeira that originated in the 16th century, during the time of slavery in Brazil and was developed by African slaves from Angola as a form of self-defense disguised as dance.

Capoeira de Angola is characterized by its slower, more fluid movements compared to other styles of capoeira. It emphasizes strategy, deception, and creativity, rather than brute strength. It also has deep spiritual roots tying it to African religious cosmogonies practiced in Angola before colonialism, and widely held in its Afro-Brazilian diaspora of today. Incorporating such cultural and historical richness could add much political valency to the manifestations of capoeira in video games like Tekken.

In Mary Flanagan’s seminal work, “Critical Play” she points to the fact that in harnessing rule-based fun, games can cause players to reflect on social, cultural, and political issues. For a character like Eddy Gordo, a Black Brazilian man, it is meaningful that he practices capoeira, and it would be even more meaningful that he practiced Capoeira de Angola, with clear links to its anti-slavery roots.

Santix Schwarz practicing capoeira de Angola

Between the economy of video games and the history of capoeira, this collaboration is one between two worlds, on both sides of racial and national identities, understood and made by the apocalyptic violence of slavery and war. Re-Mastered proposes not only a technical recalibration of these fighting styles into proposed characters, but rather an ontological, and epistemological recalibration, or RE-MASTERING.

The smooth layers of technology usually hide a messier and exploitative logic. In video games, the smooth motions of characters are captured through motion-tracking technology, underlying not only the human labor behind them but also the bias of who serves as inspiration for the digital avatars we see in video games. The motion capture for Eddy’s character was played by Mestre Marcelo Pereira, an experienced capoeira master who has been an outspoken champion of the sport.

Despite Mestre Pereira’s devotion, he is a white Brazilian who sees capoeira as a competitive sport to be formalized, not a means of fostering political struggle and liberation. Pereira is also primarily known for practicing capoeira regional, the more commercialized version of the art. What if the motion captured was performed on black practitioners of capoeira de Angola?

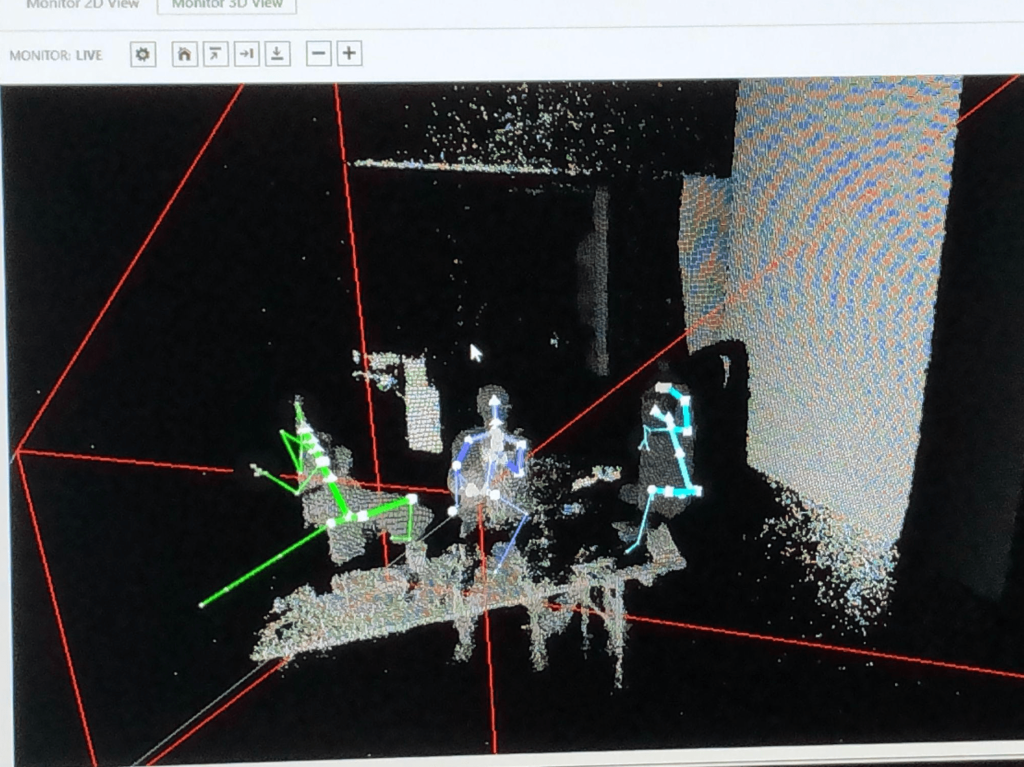

Practitioners whose markedly different religious and cultural practice was also part of the fighting movements. This is an idea inspired by communication with the work of Berlin-based Afro-Brazilian group Santix Schwarz (Black Syntax), as pictured. The recent democratization of motion capture technologies like Microsoft Kinect and 3D game engines like Unity 3D and Unreal engine would make this speculation easily realizable.

Digital tracking of Santix Schwarz practicing capoeira de Angola

However, there are also challenges, capoeira de Angola, like the fugitives from slavery that practiced it, is meant to be hidden. What are the ethical responsibilities of designers to preserve and maintain this quality of capoeira de Angola, if it can be captured by technologies, does it expose it to the same risks of capitalist exploitation we see in contemporary capoeira, and video games?

It is more interesting to ask questions than to give answers. Despite complexities in developing decolonial narratives and play mechanics in games, there is undoubtedly a real opportunity to read rich spiritual, cultural, and liberating political elements back into the frame of the video game. The title Re-Master is a play on remix culture which is characteristic of DIY culture of recreating existing things in new exciting forms, and Master, a nod to the colonial and racial legacies inherent in modern-day technologies. Re-Master responds to Audre Lorde’s famous challenge, proposing we remix the master’s tools, repurposing DIY motion capture technology and open-source software to read a political semantic back into black characters in video games.

This direction would not only make fighting games more meaningful and enjoyable, but lift them out of an apparatus of anaesthesia where we are numbed to social and political action, educating us and radicalizing us to create a more equitable and just world. Therefore, we believe that although this form of insurgent game design is not without challenges, it is important and urgent for all, especially those of us who are in search of a gravity that defies anti-blackness