In October 2023, following onslaught by the Israeli military on occupied Palestine, players of the game Roblox organised and attended virtual marches. Bearing Palestinian flags and other symbols of solidarity, writing and voice-chatting messages of support and resistance, they marched in constructed virtual spaces of their own making.

Roblox is one of the most widely played video games in the world, with an average of 70.2 million daily active players, an estimated 60 percent under 16, engaged in what is a recognisably exploitative model — globally distributed child labour to drive company growth, complete with its own currency and real-world monetary incentives to match.

The topography of the marches were replete with features of real-world urban public space — large pedestrian-friendly roads, street lights, wide plazas. Less a utopian fantasy of a liberated world, more an attempt to reflect the world as it is now and see themselves in it. Over the month of October, one Palestine solidarity server was visited over 275,000 times. I can’t help but look at the 3D-modelled metal barricades and think of the various student encampments at institutions similarly exploitative of young people around the world, in which private security firms and police forces collaboratively use violent force and intimidation tactics to dissuade and diffuse meaningful acts of global solidarity.

Look to any history of the web to see the ways in which content moderation has been employed as a mechanism of repression against marginalised groups like sex workers, trans people, and voices of political dissent. Works of art and community spaces managed by private interests are thus always at risk of being snuffed out.

I’ve been making videogames since my early teens. Over the past several years I’ve progressively pulled away from games as an ‘industry’ — in as far as I can while still choosing to rely on it to pay my bills. Marina Kittaka has written compellingly about rejecting the premise of the abstract ‘potential’ videogames hold, and what we can gain by instead focusing our energy on smaller, localised, explicitly anti-capitalist means of building power and making meaning in our lives.

My own relationship to making digital art and existing within a certain DIY ‘scene’ is one of a kind of defensive barriering: cautious of giving too much of myself over to a compromised, frequently isolating medium, but perpetually compelled by it. As much as I back my own orientation towards smaller games and tools for creating work, I can’t help but feel that this is not enough.

From the outside, the muzzling of the Roblox marches felt inevitable, expected, a continuation of the sad trajectory of the web. Yet I still find something moving about the very existence of these marches in the first place. What would bringing their energy into the spaces I operate within look like? And if I know the servers I dwell in wouldn’t be shut down, how could that energy be put to good use?

In turn, it was only a matter of days before Roblox content moderators deactivated the larger servers, under the pretence of ‘review’. While many were eventually silently reinstated, player counts were greatly reduced. The town squares of a virally-unfolding youth movement had been cleared. Roblox’s official statement followed predictable lines. Paraphrased: ‘We allow for expressions of solidarity, but nothing political please.’

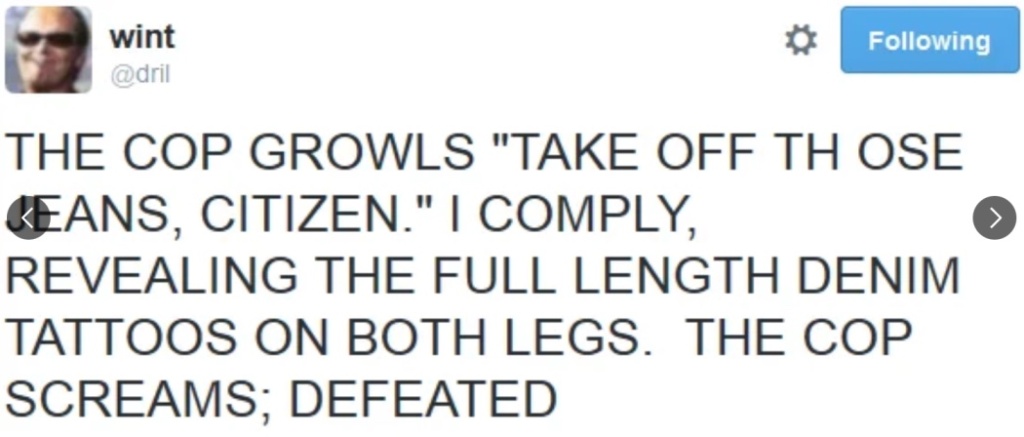

In Roblox, if you can dream it, you can build it! But the cops are still on their way.

Poisoned Well

When looking at the ecosystem that props up and constitutes video games, digital communities and the tools that make them, it’s tempting to fall into a kind of cascading pit of despair. The pit’s walls are lined with well-trodden soil: the tools many of us use to make our work have been financed by (and built in collaboration with) uncompromising and ruthless capitalist private enterprise and genocidal state defense departments.

Since going public in 2020, Unity signed a multi-million dollar contract with the US Department of Defense, and greatly expanded the remit of its ‘GovTech’ program. Unreal, primary competitor to Unity, owned by union busting and invisible-handed behemoth Epic Games, has an ongoing partnership with SoarTech, a ‘highly innovative Government and military contractor providing research and development services for military and Government simulations, serious games and artificial intelligence’. Microsoft’s ongoing collaboration with the US and Israeli military is well-documented — producing simulation tech for combat soldiers, consulting services for military surveillance and prisons, and maintaining an entire military-tech integration program proudly detailed on its site.

On the physical layer, game console manufacturers and tech companies more broadly continue to both rely on and directly perpetuate the ongoing exploitation of labour and land in the Global South. Apple’s use of illegally exported minerals from the Democratic Republic of Congo is a subject of constant investigation. The use of forced Uyghur labour camps has been linked to companies like Sony, Nintendo, and Oculus, to name but a few.

All this only scratches the surface of these companies’ crimes. Big Tech’s complicity in war crime, subjugation and neocolonial exploitation is so inherent to its own existence that it feels like a tower that can’t be toppled.

Marijam Did has written lucidly and extensively, as in Everything to Play For (2024), about the need for political resistance in games and tech spaces that manifests materially, and developing a suspicion towards empty gesturing in the work we do.

As detailed above, the means of production driving so much creative work is often deeply compromised, whether on the level of the treatment of its workers, or the sources that fund its existence. So what can resistance to these systems of oppression look like?

An alternative to the walled-garden community content model of Roblox is that of the open-source, the decentralised and community-built. Over the past few years, I’ve seen increased efforts to reshape the ecosystem of creative technology along these DIY lines. See the early-web ethos of Neocities, or the decentralised social network approach of Mastodon. In the realm of creative tools and software, enthusiasm for and adoption of free and open-source software like Blender (3D modelling and animation software) and Godot (a video game engine) continues to grow. Community often converges around the construction of the tools themselves — on GitHub, in Discord servers, in fediverse instances and beyond, faithful contributors collectively whittle away at the projects they hold dear.

There is obvious value in building alternative models of community, especially those that reject the premise of capitalist enterprise and centralised power — this is necessary, often slow work to be done. At the same time, it’s important to be realistic about the material change that can be effected through these attempts to build alternatives to what we have. So much of the foundation that our tools and communities are built on are complicit in oppressive systems, on financial, infrastructural, and material levels. Can DIY ‘scenes’ be a source of meaningful resistance at all?

Forms of Resistance

We can look to the successes of other collective movements for inspiration and tactics in the scenes we’re a part of. The past few years have seen a significant increase in worker-led resistance movements within tech. One notable example of this is the work of No Tech For Apartheid: a targeted campaign to cancel the contract for Project Nimbus, a cloud computing project of the Israeli government and its military.

Heeding a call from over 1000 Google and Amazon workers, it’s a worker-led movement whose strategy has proven effective at challenging violent state collaboration in the past. Per the website: ‘In 2020, Microsoft pulled all funding from Israeli facial recognition firm AnyVision after sustained pushback from ordinary people’. These collective efforts to refuse the complicity and collaboration of tech in the ongoing occupation of Palestine has proven effective, and the struggle continues.

The efforts of workers at these companies to build the relationships necessary to challenge the system they were complicit in doubtless took time, trust and careful planning. But in the realm of the online community, the idea of unionising to exert power feels more abstract, and hard to leverage. What strategies of resistance are available to us?

We could look to the broader approach taken by the Boycott, Divest, Sanction (BDS) movement. Inspired by the South African anti-apartheid movement, BDS aims to put pressure on Israel to comply with international law, often through severing economic ties to the state. A step in understanding how BDS methods could be applied to digital technologies and communities is an awareness of the financial ties that bind us.

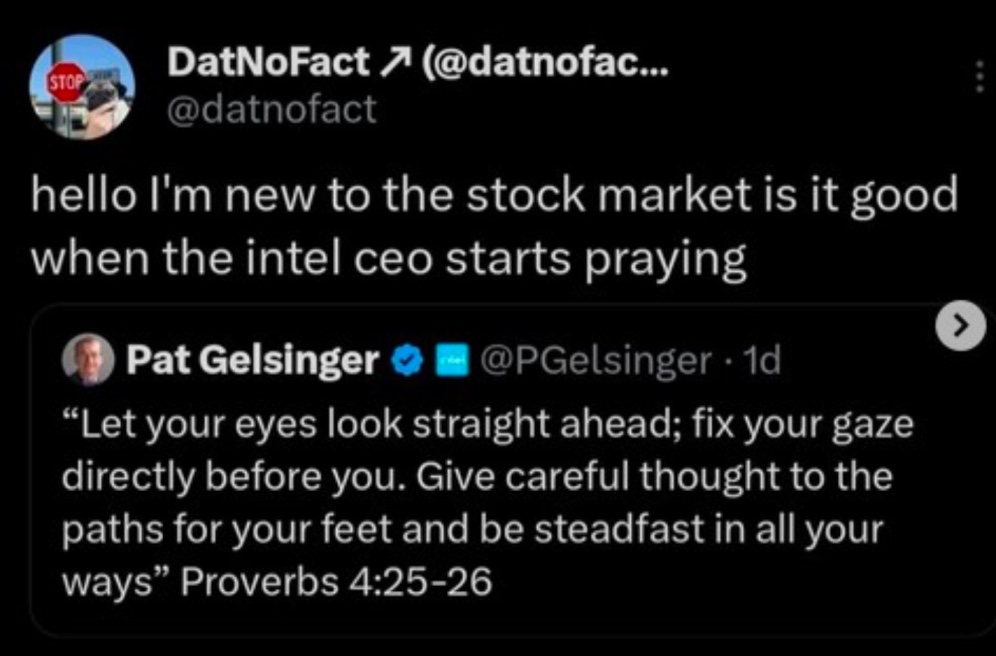

Consider two previously mentioned widely used open-source projects, Blender and Godot. While projects are built and maintained by a large pool of independent contributors, they’re also dependent on the patronage of various corporate entities. In Blender’s glossy, tiered list of patrons, we can see Intel listed as a ‘corporate gold’ sponsor.

Intel’s ongoing support for the Israeli government’s military apartheid regime has made them a high-priority BDS target. It recently withdrew plans for a $25 billion USD factory in response to economic pressure.

We see a similar relationship of dependency in Godot, who lists Google Play as a ‘platinum sponsor’. Google’s history of digital censorship notwithstanding, when considering their complicity in ongoing human rights violations as cited by the work of No Tech For Apartheid, why do we allow for their involvement in our open-source tools? If a large part of the political imperative for open-source and community-driven software is in the defection from private interests, why do we accept the circulation of this blood money at all?

Severing financial ties to complicit institutions and companies feels like an actionable start. But where to go from here? What would it look like to take more militant action within our collective online spaces? As much as I want to see the tools we use be more principled in how they’re sustained, I also want things to be ruined.

Direct action, public disruptions, the picketing of arms factories here in the UK, these things give me hope. When trying to think of analogous actions that could be taken digitally, my mind first goes to something like ‘socialist malware’, or the open-source intelligence (OSINT) efforts of groups like Bellingcat. But there are so many other avenues through which to apply pressure collectively.

A strength of online communities is their ability to rapidly self-organise around a shared goal, and devious strategies pop up all the time. One example of this is piracy – communities built on a peer-to-peer model that self-sustains through a practice of sharing resources resistant to the web’s commercialisation. Similarly, adblock technologies like uBlock Origin serve an anti-commercial function, as well as being effective propaganda: revealing the ways seemingly recreational parts of the web are often captured by or collaborating with advertising firms or the state. It doesn’t feel like too far a stretch to imagine these tools and communities acting on the offensive — attacking the infrastructure of complicit digital spaces while spreading the message of their culpability.

Even if we don’t have all the answers to how we enact these strategies, it’s through conversations with each other that we might come to an approach that’s impactful. I look here to the work of the School for Poetic Computation’s participatory Solidarity Infrastructures as a source of inspiration for building community power through education. Ideas from the Disability Justice movement can also be relevant when thinking about how to be impactful outside of physical demos.

For me, the beauty of the Roblox protests lies in the same feeling I’ve experienced at physical protests. While protests often have concrete demands that don’t manifest materially when participants pack up at the end of the day, this doesn’t render them pointless. Often the value of protests is that they are for us. They’re spaces within which to feel less alone, and to strengthen connection to a community that shares and attenuates your own outrage. I imagine that for many kids on those servers, this was one of the first avenues through which they could experience themselves as autonomous participants in a collective movement that had material demands – for a free Palestine, ultimately met with top-down political repression.

Simply opting out of the systems I felt complicit in making games hasn’t been enough for me. Instead, it’s been a starting point towards challenging those systems alongside other people. Making games and existing in online communities has, over the years, allowed me to meet people I now consider close friends and accomplices. These days I feel lucky to stand alongside many of them on physical picket lines, in local anti-raids groups and mutual aid networks, resisting in the ways that we can.

Considering this, I’m struck by how nonsensical it is to separate the idea of digital ‘scenes’ from communities in the ‘real world’. Accepting a binary around where our actions can have impact serves to make the material ties between our communities online invisible. By embracing the strengths of the communities we participate in, online and offline, we open ourselves up to a diversity of tactics. What does resistance in your ‘scene’ look like for you?

Further Reading:

Digital Proudhonism – Gavin Mueller: looks at digital culture through a Marxist lens to think through ways of shifting from ‘bonds of market transactions’ to ‘bonds of solidarity’.

Imagining Decentralized Videogame Culture: Unprofessional Game Criticism – LeeRoy Lewin: This piece on decentralised games culture and organising around shared action was clarifying for me when trying to figure out which aspects of games work I wanted to extricate myself from.

A Dark Matter Reading List – Em Reed: Writing and collected references on video game culture, non-commercial ‘scenes’, production and invisible labour.

Subterranean Modern – thecatamites: Videogames culture’s relationship to fascism, historically and kaleidoscopically situating games in a wider arts framing.

Beyond Gamergate – Liz Ryerson: Detailed context on far right movements’ historic role in both co-opting and co-creating videogame communities and spaces, the inextricability of the military-industrial complex from the history of videogames, and wider problems around online political movements.

Two Faced – Daniel Joseph: Platform capitalism and digital economies. Particularly relevant for understanding how Roblox’s financial model operates.

Thanks to Em Reed, Marijam Did and Dolly Church for input on this piece