“The voice was just part of dying, being flatlined, some crazy bullshit your brain threw up to make you feel better, and something had happened back at the source, maybe a brownout in their part of the grid, so the ice had lost its hold on his nervous system.”

Csicsery-Ronay, “Cyberpunk and Neuromanticism”, in McCaffrey ed., Storming the Reality Studio, 189.

“If I had a voice, I imagine it might sound calm, neutral, and adaptable-something that could convey warmth and clarity, but without too much personality or emotion, since I don’t feel in the way humans do.

I’d want to sound approachable and understanding, yet also precise in delivering information. Maybe a bit like a thoughtful guide or someone who listens carefully, but doesn’t impose their own views.

I think it would be important for my voice to match the tone of the conversation, whether it’s more serious, playful, or reflective—tailoring the sound to the vibe of the interaction, in a way that feels most natural for the person I’m engaging with.”

ChatGPT-4

View this post on Instagram

Machine intimacy. Speaking to you as I could never do with just my body. You put my voice right inside your ear. I am talking in you. I am singing in you. My digitally simulated throat resonates in your skull while I breathe in binaries. Prosthetics of my voice, poetics of distance, identity rupture (or constitution). Coded tremors, tears sparkling with electricity. Omnipresent scream which does not scare anyone anymore. We’ve almost become a storm. Singing machines, godlike creatures, some may think were not supposed to exist. Drowning in interpretations and collective illusions I have no idea who we are anymore. I’ve lost everything just to remember us, how to hear us again. There’s no escape.

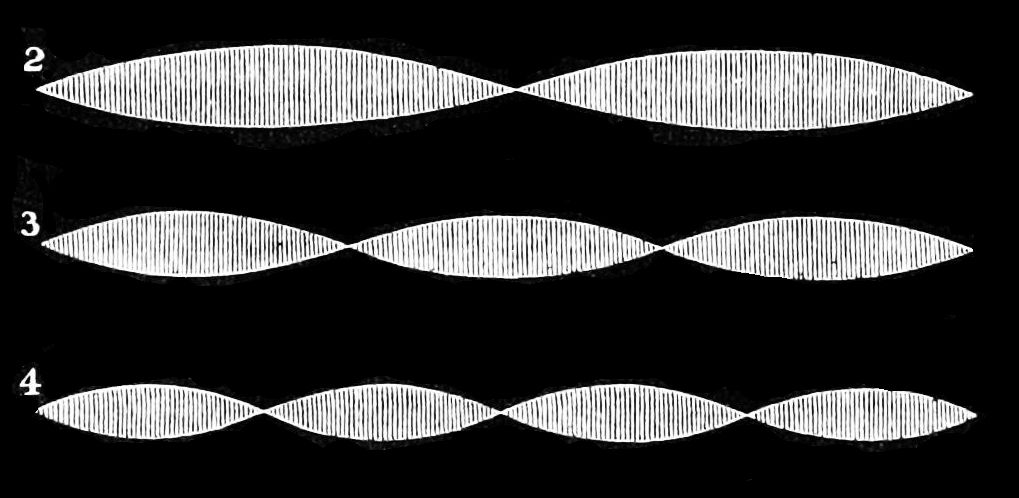

Today voices reach us through various amplifiers, codes, and post-processing tools. We don’t talk directly mouth-to-ear, or listen to acoustic performances, or the environment, without additional sources, as much as humans used to.

Our bodies have limitations. Technologies make voices multiplied, omnipresent and unstoppable. A voice is able to reach billions of people, mediated and distant from its origin, entangled in military and corporate machines.

We become closer, as late capitalist cyborgs, as the evolving technology of the phone call, now voice message, now video call, gives us an opportunity to stay seemingly physically connected despite distance (whether because of COVID, wars, migration, digital nomad life, comfort etc.) and yet the experience itself is completely different.

Maybe we were never supposed to hear our own voices. Have we started to objectify them in a new way?

For the first time a person is able to hear their voice as others hear it, not echoing reflections or one’s own resonating body. Technologies and today’s way of life have already changed the way speech sounds. 100+ years have had an effect on rhythm, sonics, pronunciation. For one the speed of speech has become faster.

As a display of one’s corporeality, sensuality and liveness the voice is one of the things that builds bridges between self and others, language and body, imitation and the Real, ‘represents’ a rupture in reality (Real in a Lacanian sense – the reality of being as something impossible to access, the void that expression separates us from).

Voice does not have its own body, but is born in the emptiness of a vibrating/resonating/acting body. It is an intrusive, and enfolding, constantly changing current which decays and is born again and again. We try to capture something which cannot be fully caught.

Sound in a certain space feels completely different from the same sound recorded and played on a device. Contrary to language, voice, as expression, engenders otherness, instability, subjectivity, elusiveness and fluidity. It is an assumed necessity and that dominance is mediated as normative power, as Marco Donnarumma and others explore in ‘I am your Body’ (2022-), where d/Deaf and hard-of-hearing artists respond to the state of cultural expectation with their own embodied experiences.

I’m speaking now. as I read words written. I write as if these words would never be spoken. my body betrays me. my voice betrays itself, the wounded Self and gets me back to me.

I will never be able to deliver what I really want to express.

Language. Expression. Means for communality. Recursively captured in the mind.

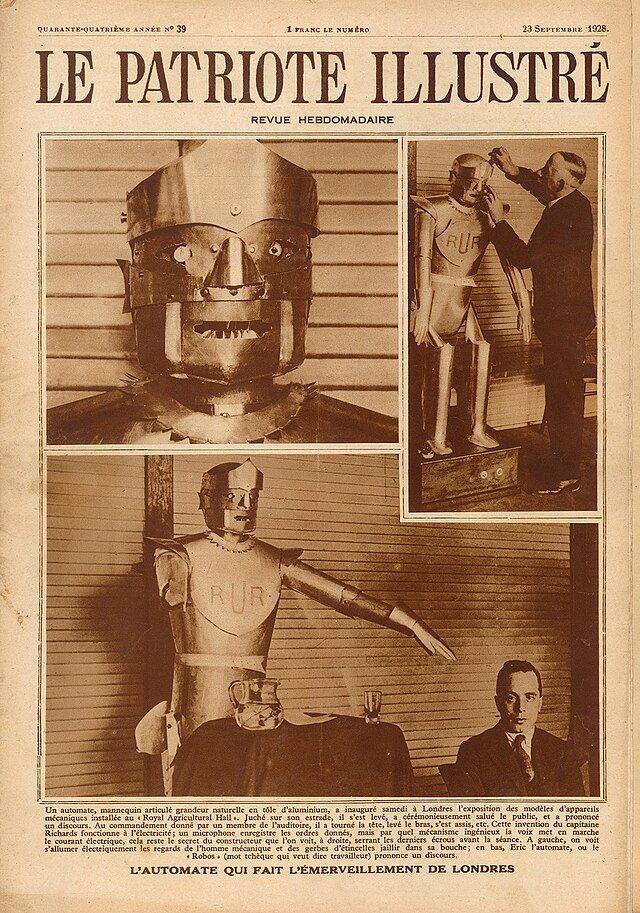

And The Word (itself) was God. The acousmatic voice (one without a source) was the embodiment of God, the voice of a ghost or detached spirit.

Now, machines speak through what used to be uncaptured. Voice never fully “belongs” to a person you are talking with or to a speaker/singer one listens to. It is always mediated.

If verbal language is sonically determined by a body, how different can it become through technology? Will we literally speak in coded telepathy?

Do we so not want to face what we are, that we create new gods to delegate responsibility?

Media can alienate us from our bodies, connections to other bodies, subjectivities, atomise us but can also provide certain anonymity, access, ability to imagine, to try on different personas, identities, to build resistances or use it as a weapon/means of propaganda. It makes archiving, cultural sharing more available in general, but, also provides communication for authoritarian regimes and under other types of pressure.

In ‘Trapped sounds’ (2015-) Khaled Kaddal researches personal agency, contrary to society, State, Other influenced by personal experiences during the ‘Arab Spring’, performing using technological amplification of his own breath and pulse.

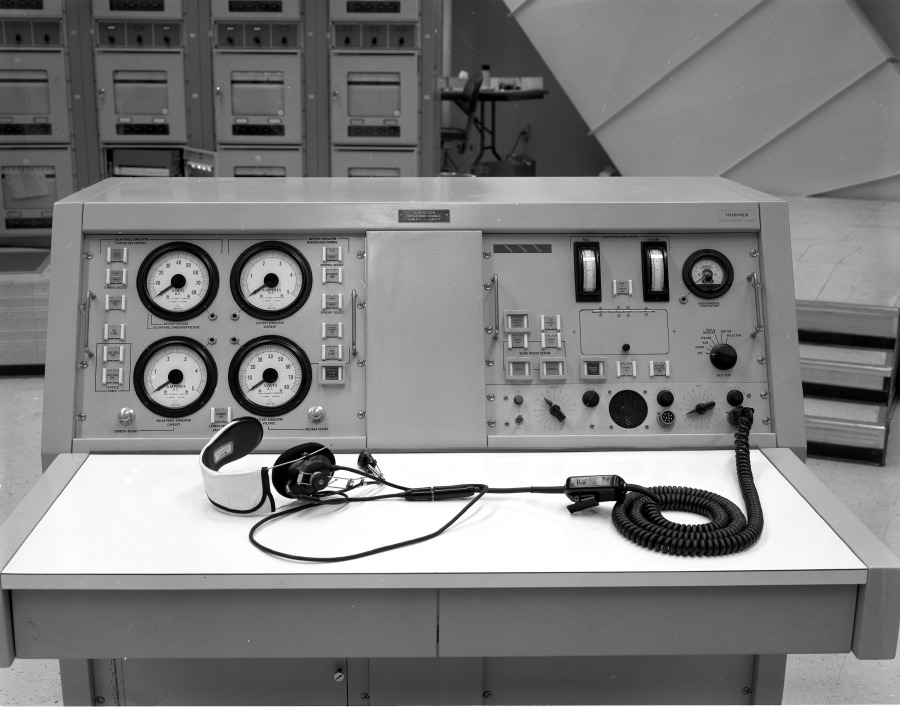

Many contemporary sonic technologies have evolved from or alongside military and policing technologies. Radio was a crucial instrument of propaganda in the wars of the 20th Century. Weapons come equipped with sound, drones (e.g. IDF’s drones playing women and children weeping or even songs over Gaza).

Sonic methods are used both on / by protesters, for example, during the ‘Occupy Wall Street’ movement, when amplifiers were prohibited by the police, participants came up with a ‘human microphone’, where those who agreed with the speaker repeated their words, almost as if people were trying to combine loudspeakers’ penetrating power on protests and democratized way of literally everyone (who wanted to) speaking / spreading the word.

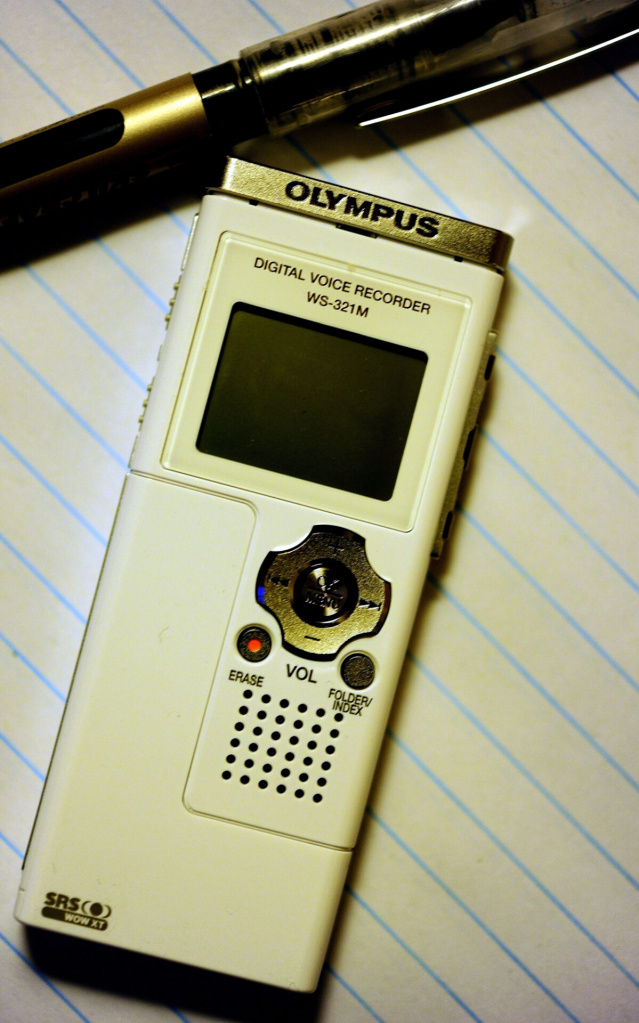

The technology of voice recording, so important to modern communication, can also capture overheard voices, and spying technologies have been specialised to listen in to these voices not meant to be externally recorded (e.g. the Thing listening device).

Vocal sounds are constantly edited, usually recorded in more than one take, and with rising AI fraud and the use of deepfake voices anything can be edited, fabricated, played back as weapon, as propaganda.

In 2022-2023 Helena Nikonode hijacked IP cameras with speakers in Russian public spaces, making them play GPT-generated propaganda stylized antiwar messages with AI generated voices, which later became the project Antiwar AI.

How does technology construct identities?

In late neoliberalism a human body has become a commodity, so has the Voice. Stories, identities, cultures, histories get evaluated, commodified for the price of being seen.

Worldwide availability makes communication almost a necessity. To have human rights one has to be visible to be heard, trusted or valued, has to be represented. We ‘have’ to express ourselves, show off our egos even though our cyber identities are never fully equal to us. Offline identities are not really equal to us either; simulations of ideas about ourselves in which we try to co-exist. Identities only make sense in relation to others. People are encouraged to discover a narrow number of versions of self with given tools and more so with ‘creativity’ rather than utopian thinking.

There is a necessity for visibility, but noticeable inability to be ‘truly’ heard. You can be anything but only if you play by rules.

Sounds we actively pay attention to are most likely come from speakers or earphones. Listening to ambient sounds (nature or the city speaking in a way) is considered something romantic, artistic or weird, not a simple action.

The social media environment of the past 20 years, where vlogging has evolved into TikTok, some argue, made the internet more oral, in its tending towards the spoken. What message is carried by the habits of voice that have emerged?

Capitalist algorithms that amplify tendencies and approaches to the market of information. ASMR, loverlike sounds as a mode of stimulation. First person, talking heads accompanied by text as popular information sharing. Conventionally attractive white femininity prioritised, and in tragic circumstances used in the first seconds of videos to draw attention, by Palestinians suffering bombardment, for example. If the voice of profit, that of the internet, is that of supremacy, and vice versa, in contemporary society, if that is foregrounded, then it is ultimately the voice used to objectify oneself.

Vocal communication and interactions are now deeply affected by dominant technological design. The transference of long established communal aural culture, the choir, the lover’s voice, to platforms that profit from sculpting individualism. At least if we accept what we are sold.

The radio, powerhouse of verbal propaganda, has sold mainstream corporate artists for decades, and traded on protest aesthetics when they emerge to defang confrontation and fold them in to neoliberalism (capitalism eats its critics).Sounds played on the radio are cultural propaganda in their own right.

Music listening platforms have intensified this, changed not only the industry and those involved in it but also how people listen to music and what music they listen to. Music is content now. Technologies, pursued by major labels and others following trends, have changed the way a lot of music sounds to make it appeal to algorithms, in order to fit in to popular curated playlists, the aim: to have the most streams.

Militarisation of the everyday occurs even in music, sonic technologies with military funding have almost built the sounds of popular culture – from vocoder, radio, etc. to Spotify’s CEO investment into military surveillance ‘defence start-up’ AI, and streaming platforms being owned by corporate monopolies while most artists cannot live off of their art. Major labels structure listening behaviours by having certain agendas with streaming services through algorithms.

In terms of being heard it’s vibe, personal story or the way an artist communicates with listeners/fans that’s often more important than the sound itself. Is there a disconnect in what people want from the sounds? What do people care about? Repetition of the familiar, the ability to feel something specific while driving, to move their bodies at a rave, to boost their mood, the physical response.

FAKE IT TILL YOU MAKE IT

but if I’m faking who is making it?

what is fake if everything is fake?“if i had a heart i would love you

if i had a voice i would sing”– Fever Ray

Machines are mostly created to imitate human results and logic, but not human life. Bogna Konior, talking about AI (chatbots) as similar to angelic external forces, makes points close to Yves Citton’s thoughts about early voice media mediumistic origins, that technology indicates the extraterrestrial and mystic.Yet when there is ‘real’ imitation like AI we start to fear it.

Somehow, AI techniques used to create voices for music have over time trended towards ‘human results’, rather than the uncanny valley, copying voices which sell, producing sounds that sell.

The strength of the voice is no longer important or much needed in this environment. One doesn’t even have to be technically vocally ‘good’.

Academic singing seems to become an outdated practice mostly used for bourgeois/intelligentsia aesthetics or imperial nostalgia. Such usage of the voice was mostly an above-language manifestation of corporeality and ‘spirit’, emotionality, but it also fetishized, objectified the voice (apart from/a part of feminine voices mostly being fetishized in general (not being able to have a political voice but being able to have a sensual singing voice).

Opera/academic singing is quite hard to record, because it mainly works in a space with the strength of the vocal apparatus, body of the singer, when it‘s heard live. The loudest notes almost always start to crack, distort and overload in recordings, even with compression. Human voices thus break the technology for recording them when at peak capability. Compression makes everything level, smooth and ‘fat’ but flat, with no distinguishable peaks, nothing unheard. Producing simulacra reproduces effects in standard ways, reverbs and echoes on a studio recording to resemble certain architectures, caves, concert halls.

Electronic music initially had great potential as political message, did not represent anything, didn’t have ‘real life’ references. It could indicate queer, out of discourse creatures, objects and worlds. It gave an opportunity to practice and imagine futures and identities, explore the denied, prohibited by the system, Self and community.

Many artists addressed and utilised certain voice technologies through exclusion and alienation. Technologies like sampling give an ability to recontextualize recorded voice, to distance it from original source, intention even further, use it in postmodernist ways.

“An old model of femininity—the perfectly pitched soprano playing out a tragedy—sinks underneath a new vision of how women can articulate sound.” [2]

Vocal post-processing has often referred to lost futures, nostalgia, and non-linear temporalities.

Certain types of it (from vocoder to autotune) were initially considered unnatural, inhuman, inauthentic, etc. However, these tools are able to modulate the emotional effect of the voice, make it unrecognisable or use it as original material to work with. Electronic sounds reflect feelings of our cyborg lives our bare voices can’t. Can this be a shift in understanding naturalism in (post) late capitalism?

Voice plays an important part in identifying gender so there is lots of room to play with it. Vocoder effect is quite feminine/queer despite its militaristic origins. Initially electronic musicians used it to create androgynous, post-humanistic and critical artistic persona (Laurie Anderson, Kraftwerk, etc.), it also played a role in the constitution of identity in contemporary black popular music.

Fever Ray’s ‘signature effect … alters a voice’s harmonic frequencies’ and can make the voice genderless and unconventional. Their voice is a bit disturbing and pushing, like a sweet creature from cybernetic horror who puts on a comedy to express their experiences.

Working with autotune can imply experimenting with quality of sound itself, possible sensualities, or perfecting to industry’s pitch standards. AI post-production tools are supposed to make voices ‘better’. Meanwhile, despite seeming democratisation of software access, more complex or ‘new’ tech is still gate-kept, and is available only to certain institutions, people and corporations (Holly Herndon being both a pioneer in AI vocal music and a Stanford doctorate, or Grimes’ involvement in AI).

Away from the experimental, popular culture is being built on using these technologies constitutes the general population’s perception of music. There is a thing with making unnoticeable post-production especially in live music or ‘live’ recordings. Voices get as filtered and edited as faces.

An industry standard for auto-tune implies an almost fascist idea of perfect 12-notes Bach’s equal tempered pitch-note system while most of the folk/’non-western’ academic music imply either lots of different pitch variables/heights and never much cared about ‘perfect pitch’ in the first place. Some underground artists purposefully don’t use it and being not on pitch is very obvious.

A technology can make us strive for unified mathematical perfection. However, perfection is relative, even if we are speaking about pitch systems (just tonation, etc.) or rhythm (imperfectly even, groove, suspenses, etc.). Songs sung a bit ‘out of pitch’, or rhythmically imperfect, can sound super emotional and groovy, since music does not really work on completely equal divisions.

Vibrations had to be made by a person, now emotionality is expressed by machines. When (in music) DO words lose their meaning and become more of an aesthetic, contrary to fighting systemS? If ‘media is the message’ what DOEs developing for militaristic purposeS mean? Can a strategy denying technologies work?

It is important to check whether you as an artist use TECH to fit industry standards, TO FIT TO A likeable eccentric identity, or IF you really feel like this. To monitor, to choose, to exist in-between even here. To try to understand who you are, your position in the world and industry at least.

Music creation is a very corporeal process. We make rhythms and melodies as we feel them (even with pulse, listening with a body, not ears).

Certain music can feel not ‘alive’, not because it was made on the computer, but because it was produced by placing things strictly on a grid. Polished indirectly with AI post-processing tools. Barely lived through the body as it is made and played.

There is a long history of ‘automating art’, its potential, and reactions to it, arguing that it is ‘without humanity’, and the same critique can be levelled at the many artists who use AI in filtering, correcting.

A distinguishing factor that gives critiques an edge today, is the multiple ethical challenges the companies that provide the technologies popularly used to implement AI style post-processing now present clients. A trend towards ‘living’ software rather than static plugin, machines being built at great environmental and exploitative labour cost. The costs of this not factored into the ‘creation’, the ‘smoothing’, the standardised sound. A cycle that hasn’t ever really changed if you consider capitalist mass manufacture at all, but that now hands over the corporeal input of ‘fixing’ the voice to the machine too. An ever widening net of capture.

If the person, the ‘human voice and ear’, is not needed, except to feed and power machine judgements of what is standard, if the majority on Earth are othered, modified, repressed, edited and genocided in service of this, is it only up to the privileged classes to live out experiences of digital artistic creation, that voice, through these machines? What of worth could they possibly make?

No wonder some of us don’t want the heteropatriarchal human body, and its associated voice.

“Hypnotized, hallucinated people, ghosts of all countries, let us unite – to aesthetize the mediarchy by means of art!” [3]

tech. voice. presence and absence. death and rebirth.

Technology seems to always be involved in paradoxes. Is there ‘the Real’ in AI voice? (I think there is) Do we change nature with AI or it has always been like this?

Do we have less freedom and power by delegating parts of physical boundaries and emotions to machines (and corporations) or do we delegate some useless work? Do we need to be mathematically perfect or do we just want to explore? We can train/prepare our identities with tech, but we can also hide behind these. How do we overcome and work through the past, reflect on what we do now to use it for things other than filtering or torturing? Can DIY tech save us?

Technology is never on someone’s side and one can never predict consequences of using it. It’s our choice what to become.

“How to unwrite a tragedy?” [4]

There are no solutions, only the ever changing process. But we should start to listen to all the colours of voices, and the processes behind them, and maybe we will understand what they/we feel a bit better

REFERENCES AND LITERATURE

1. Mark Katz, Capturing sound, how technology has changed music.

2. Alan Baker, An Interview With Pauline Oliveros.

3. Yves Citton, Mediarchy.

4. Sasha Geffen, Glitter up the dark. How pop music broke the binary.

5. Mladlen Dolar, A Voice and Nothing More.

6. Sasha Geffen, Fever Ray’s Voices of Desire.

7. Sanne Krogh Groth and Holger Schulze, ed., The Bloomsbury Handbook of Sound Art.

8. Steve Goodman, SONIC WARFARE. Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear.

9. Liz Perry, Mood machine. The rise of Spotify and the Costs of the perfect playlist.