“Big companies use technology to make money off us, macho computer scientists make it feel exclusive and untouchable, and governments use it to silence and control us. Historically, new technology has always been a source of fear. It’s time we turn the tables around and use these tools to empower ourselves instead. It’s our turn to be feared.”

Liane Décary-Chen

Two years ago, deep in lockdown, I read Sadie Plant’s book Zeros + Ones. Subtitled “Digital Women and the New Technoculture”, it’s a curious, amorphous work underpinned by feminist, technological, biological, and medical history. Beginning with Ada Lovelace and the Analytical Engine, it traces the evolution of looms, punch cards, early computers, and code, with enlightening and sometimes unsettling detours into bacteria, botany, chromosomes, and psychoanalysis. It’s a wild ride, and it changed the way I think about feminism, technology, and networked systems.

Zeros + Ones, Sadie Plant, (Front Cover) 1997

From Lovelace to Lynn Conway, women have always been instrumental in the development of computers, and yet despite that, as in many fields, the perception and power around computing has been dominated by cis men.

In the early 1990s, as that gender disparity continued to make itself felt, modes of resistance began to emerge as hundreds of researchers, programmers, and writers shared tools made to create and control web-based systems, with inspirations and reverberations in the work of Donna Haraway, the VNS Matrix, Sadie Plant, and others. This work has broadly coalesced as cyberfeminism, although as Mindy Seu’s work on the Cyberfeminism Index highlights, “the term itself has been contested, reimagined, debunked, and expanded.”

When Zeros + Ones was published in 1997, I was seven years old, and computers were just appearing on my radar. There was one in my classroom at school that we used to play basic, pixelated educational games. The computer made me nervous. I didn’t understand how it worked, and I was afraid of triggering some kind of meltdown that would get me into big trouble. A boy in my class, Nicholas, was sent over to help me. Good. I felt safer. Yes, this was objectively anxious early me—but I also now feel sure that, at seven, I had already absorbed the message that girls don’t know about machines.

Fast-forward 25 years and my work in music journalism, passion for electronic music, and interest in sound and digital art (especially by artists who aren’t white men) have converged so that reading Zeros + Ones naturally leads me to question cyberfeminism through a lens of music, sound, feminism, and gender. Delving into the work of musicians and sound artists in my home city of Bristol and elsewhere has led me to look at electronic music and sound creation as branches (off-shoots, nodes, tendrils) of cyberfeminism. Intentionally or not, the results of both practices often cross over: building online connections, creating offline communities, and subverting patriarchal power structures.

[PART 1:] Women’s Work

“weaving is for oppositional cyborgs”

Donna Haraway, A Cyborg Manifesto

Sadie Plant’s 1995 article The Future Looms: Weaving Women and Cybernetics laid out the intrinsic link between the post-WW2 development of cybernetic technologies and the millennia-strong concept of “women’s work”: weaving, stitching, connecting, wiring. It traces the genealogy of the loom to the computer, and women’s role in the whole long process. The discussion also draws on Donna Haraway’s 1985 essay A Cyborg Manifesto, a pioneering work exploring machine-human relationships through a feminist lens. The Future Looms was later developed into Zeros + Ones, in which many of its ideas are expanded.

In the years since Zeros was published, massive shifts have taken place in both information technology and in how we understand diversity of all kinds, related to the growth of intersectional, digitally connected social justice movements.

But some tech developments have continued along the same unsettling lines that Plant identified: “female” AIs (Alexa, Siri, Cortana and co.) at various times programmed to be coy and submissive; border agencies extracting data from asylum seekers; period tracking apps feared to be leaking data to authorities that have banned abortion; and computer sciences still dominated by cis, white men, to the disadvantage of everyone else.

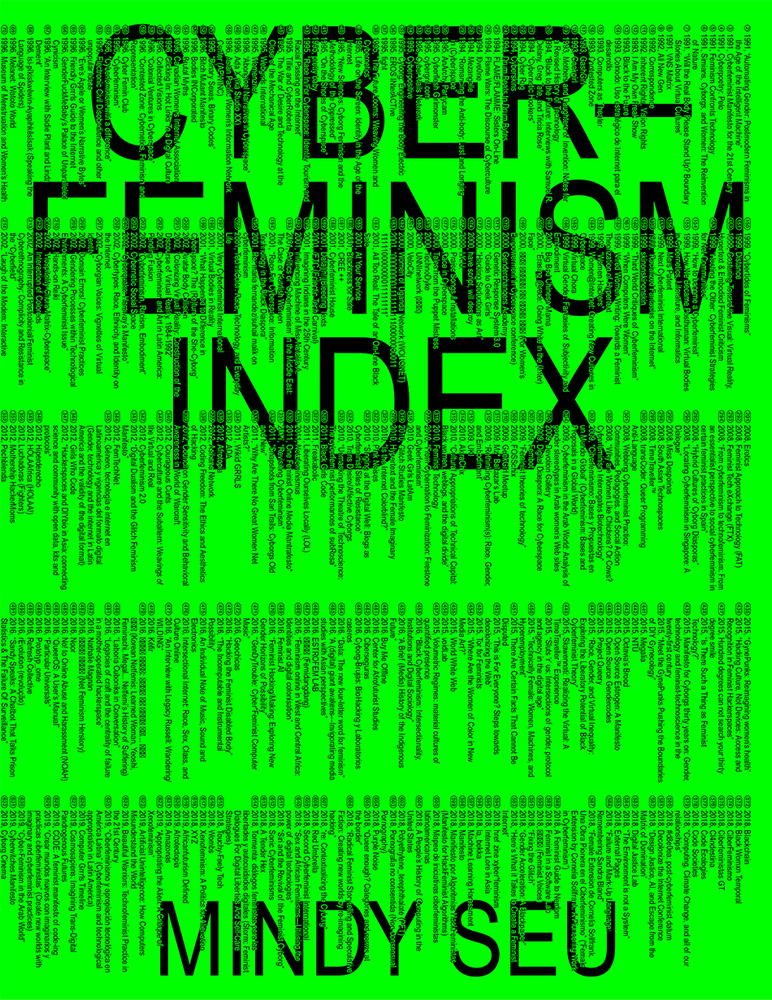

Cyberfeminism Index, Mindy Seu, (front cover), 2023

Parameters shift, but the major problems of unequal access to technology (and the types of control that come with that) remain.

So, what shape does cyberfeminism take today? On a superficial level, its nostalgically clunky visual aesthetics anchor it firmly in the 90s and 00s, its technological moment in time. But on the level of what matters, feminist and other activist work to address online power imbalances has continued, as even the briefest glance at the Cyberfeminism Index confirms. Helen Hester and others argue that the movement has evolved into post-cyberfeminism.

However we look at it, as long as Big Tech remains a patriarchal force—as attested by the examples above—then cyberfeminist battles remain alive and kicking, no matter the name or guise. We just need to open our eyes… and ears.

[PART 2:] Audible Reverberations

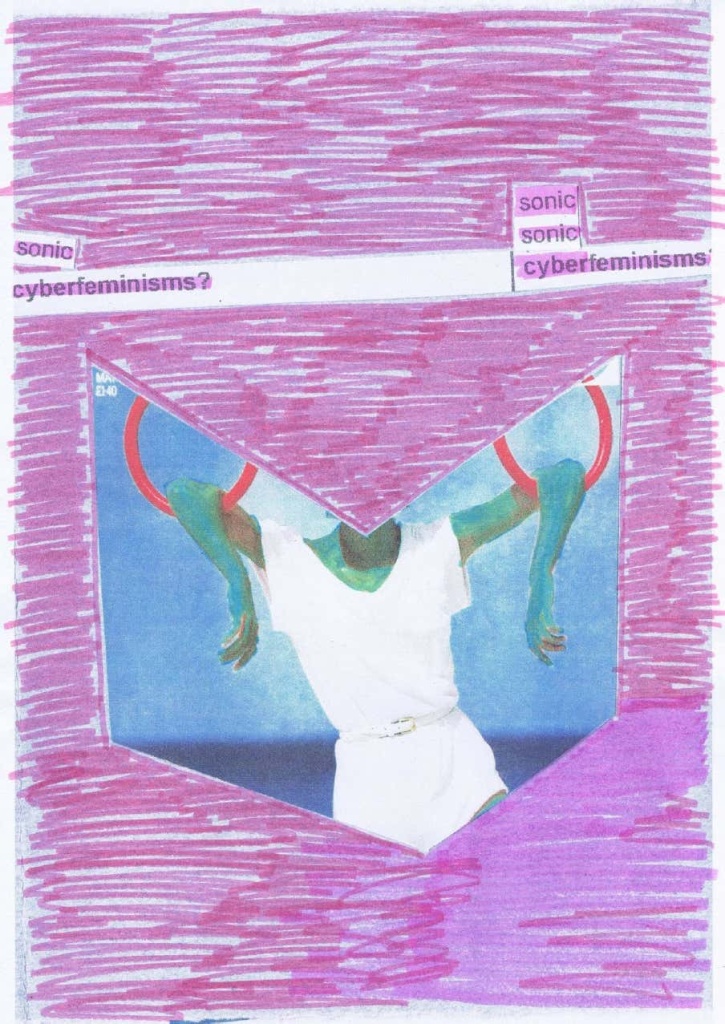

Sonic Cyberfeminisms Zine, (front cover) 2018

One of my key interests in music journalism is how musicians and artists counter the cis male dominance of electronic music and sound. When we look at the evolution of cyberfeminism from this angle, as the Sonic Cyberfeminisms project by Annie Goh has done, electronic music’s use of technology ties it into the lineage of weaving to computers and cybernetics. For decades, the work of electronic and sound artists has stood against the status quo—think of the pioneering work of Laurie Anderson, Patrick Cowley and Sylvester, Holly Herndon, and SOPHIE, to name just a few—with music and sound serving as powerful forces in community-building.

Virtual Networks

Archiving and cataloguing fit into centuries of so-called women’s work: scrapbooking, journalling, photo albums, keepsakes—and even, as explored in Zeros, botany. Plant life and specimens, URLs and databases: much like weaving, this work has long been positioned as anodyne, menial, unlikely to spark any revolutions.

But collections are powerful. Databases and email lists have been some of cyberfeminism’s key tools for collating and disseminating information.

Mindy Seu uses the term “gathering” to describe her meticulous collection of user-submitted resources for the Cyberfeminism Index, citing Ursula K. Le Guin and the idea of “methodical, deep labour that comes from ‘looking around, rather than looking ahead,’ from gathering rather than hunting.”

Programmer and researcher Liane Décary-Chen, who has worked with Montréal’s Ada X feminist artist-run centre, has described creative periods of “lots of writing, messaging, spreadsheets, and Pinterest boards. I love doing these tedious things and it definitely helps push larger projects.” Elsewhere, the female::pressure network hosts an ongoing database of LGBTQIA+ individuals and women working in any aspect of electronic music.

The idea of the power of the archive led me to think about different kinds of information that can be catalogued, and the kinds of archive that exist. One of which is the sound archive. Can building a sound archive be a feminist act? A work of cyberfeminism?

Q(ee)R Codes logo, Anna Raimondo

Anna Raimondo is a visual and sound artist living in Brussels. Her Q(ee)R Codes project, part of the Nouvelles Frontières festival in Brussels in 2022, is a mapped sound walk of the city centre that includes voices of cis and trans women and non-binary people. The QR codes on the map allow participants to access recordings for the locations they visit on the walk.

When we think about what a sound archive is and what it does, interesting parallels emerge with the work of cyberfeminism.

First, the sound archive: like a statue or monument, an archive both preserves stories for posterity and asserts the value of those represented. Just as the infrastructure and monuments of a city like Brussels reinforce white, colonialist, and patriarchal power, Raimondo’s sound archive gives space to voices of communities alienated by the public space: people of colour, the queer community, the trans community, women. By connecting these perspectives, the archive and map sketch a constellation of marginalised voices that gains force in its connectedness. Where cyberfeminism’s databases collate information to magnify its potential, Q(ee)R Codes collates and maps stories to create a dataset: a whole new tool.

Second, the sound archive: what makes the sound map different to a collection of written texts, for example? Sound carries a lot that text doesn’t. As part of the sound walk, the speakers’ words graft onto the listener’s experience as they move in physical space—and when space is not neutral but gendered, racialized, and politicised, this experience has a lot to tell. This melding of lived and heard experience has an immediate, visceral power that printed text doesn’t convey.

IRL Networks

By its nature, cyberfeminism has mainly been done in the digital realm. But access to online tools isn’t universal, and the power of IRL community remains in collaborative, DIY, grassroots projects serving as a radical alternative to Big Tech’s top-down systems. The hands-on aspect of these projects brings people together in a different way to work that exists solely online.

The work of Manchester-based sound artist, musician, and researcher Vicky Clarke is a dynamic force in this regard. In 2022, the Dreaming With Machines youth program brought together a group of women and people of marginalised genders to create “dream transmission” digital artworks. Through discussions and workshops, participants explored negative impacts of AI as well as its potential as a tool for positive change. As Clarke has explained, through its reappropriation of these technologies, Dreaming With Machines “address[ed] an imbalance in the mainly dominant male AI circles—whether academic, tech industry, or musical.”

Dreaming With Machines, Vicky Clarke (2022)

Music tech, too, can feel like an exclusive and daunting realm. Researcher and sound artist Jasmine Butt works with Bristol Communal Modular, a project that aims to “make modular synthesis, and music tech in general, more accessible, understandable, and available.” Without an explicitly gendered agenda, BCM nonetheless helps counter the male dominance and exclusivity of sound technology: its weekly meet-ups and open days at Bristol’s Hackspace, as well as workshops and events around the city, make the project visible and accessible for a more diverse range of people.

In both cases, the sensory experience of feeling sonic vibrations has its own radical power. Clarke explains that “on a practical level, my work with DIY tech is sociable and really hands-on (…) Music making and transmission through digital or physical spaces therefore are powerful connectors.”

Sound and music become the physical matter to be worked with, while the technologies used to channel and manipulate them—whether wires and circuits or digital tools—are the machines. Coexisting with these machines and finding a synergy with them, just like with the new looms that were once both so embraced and reviled, allows the march of technological change to be harnessed and reappropriated by those often excluded from positions of control.

Meeting, catching up, soldering, wiring, stitching, connecting wires: I can’t help but think of groups of women throughout history gathering to weave.

Where Zeros + Ones found resonances between the history of “women’s work” and the blossoming counterculture of cyberfeminism in the 1990s, it’s both intriguing and heartening to trace these resonances today. Turning an ear to their manifestation in sound art and electronic music reveals new layers of connection. Much more than just an echo, the core of cyberfeminism may yet live and breathe over 25 years later, shifting and mutating as much as the technology with which it is intertwined