LIVERPOOL, UK. Head down past Bold Street’s overpriced pizza joints and into the labyrinth of the Ropewalks and you’ll find FACT, cinema, art gallery, and more or less an island of its own within the city.

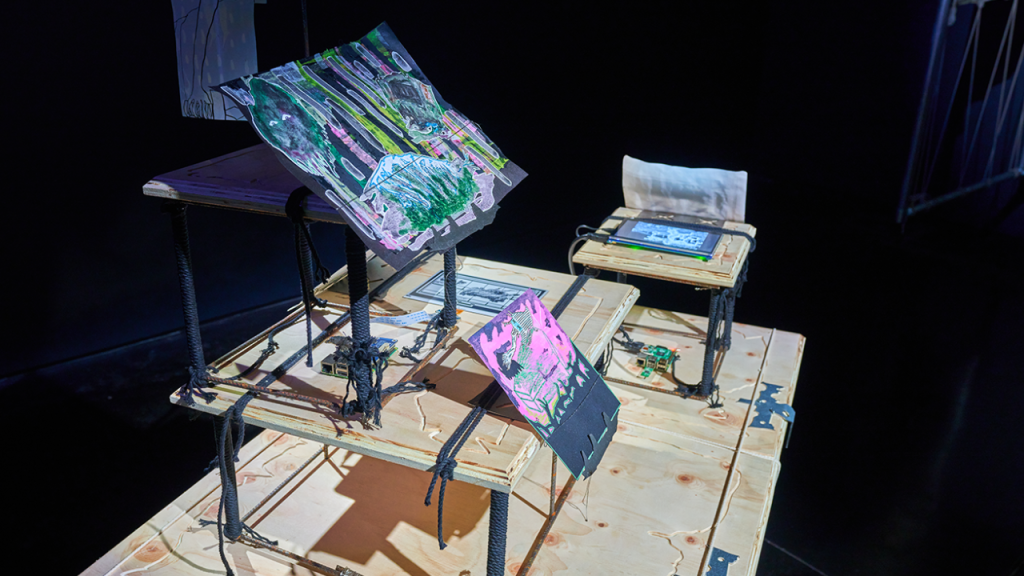

Within is Earth A.D. 2, the second form of a travelling exhibition by Uma Breakdown, showing until January 28th, 2024. An unassuming room on the first floor, but one so dense with sculpture, electronic displays and obscured details that it feels like a world unto itself, an island in the island.

Stop here and save your game. Yes/No?

Uma Breakdown, Earth A.D. 2 (2023). Installation view at FACT Liverpool. Photography by Rob Battersby

A week after my first visit to the exhibition I talked with Uma over Zoom, echoes of the room and its beguiling purpose bouncing around my landlord white walls.

Uma: “Somewhere between a mausoleum, a morgue, the archive of classified evidence you see in The X-Files, this big repository of things, and a bit like a potting shed, a place where work is done on tables, and like an improvised field workshop, maybe something like a field hospital, the temporary set up you’d have in an archaeological dig, the tables with objects invested with ideas or some kind of history.

It’s a place for dealing with things that are invested with some other power or a kind of life resonance or meaning beyond themselves, whether that is a dinosaur bone pulled out of the ground or the crankshaft you’re not sure where to use in the game. So for Earth A.D. 2, the tone shifted slightly, the save room becomes one of the images that’s at the front.”

Uma Breakdown, Earth A.D. 2 (2023). Installation view at FACT Liverpool. Photography by Rob Battersby

It is all these things, but I had save rooms on the mind, those refuges of chill vibes in survival horror games. Earth A.D. 2 contains many of their usual trappings—a bottomless box for keys, ammunition, healing items and dangerous chemical reagents, here rendered on e-ink display. Soil for herbs to grow, perhaps already harvested by another player, or to be readied for the next. A musical accompaniment, Trent Reznor’s score for Quake, albeit in a crunchy synthesised form, buzzing out of a single speaker for a Bitsy game.

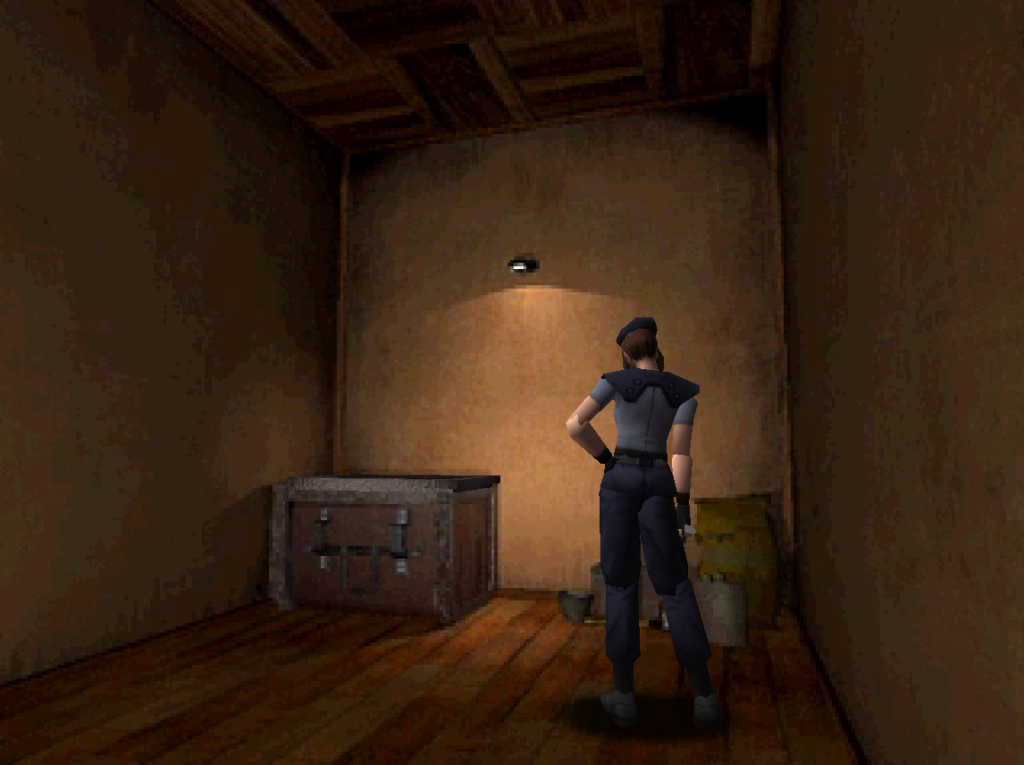

Resident Evil (1996, PlayStation, Published by Capcom)

Uma: “The thing I love about safe rooms is there’s no time limit, you can sit at the shrine in Dark Souls for as long as you want and nothing bad will happen.”

Save rooms, safe rooms. Interchangeable, for they represent both the ability to make a record of your progress, one that while sometimes requiring a finite resource, provides you with a safety net—if that zombie dog chews out your throat, you will only lose time, not your life, you can try again. This is of course is not a function afforded to us in reality, nor is the pause-

Uma: “I love the idea that time can just stop, sometimes that’s something I want more than anything. I don’t want to be a shark.”

In this recorded Zoom interview, it displays our faces when we speak. But here, for some reason, the program focuses on mine as Uma says this, in the room I refer to as a coffin. I nod, my eyes shut, give a smile somewhere between recognition and a grimace. Of course I have wished for something similar, that if I could not be in control of space, then at least time. But when Uma talks to me about the coffins littering the exhibit, they don’t mean it in sense of grim confines, or even death-

Uma: “I’m interested in coffins as a reparative device, it’s a thing for looking after people…”

I can see their point. That they affectionately referred to the “gender coffin” from Dark Souls 2 by the same term I myself used in my coming out piece suggests that we both value the coffin as something beyond morbid symbolism.

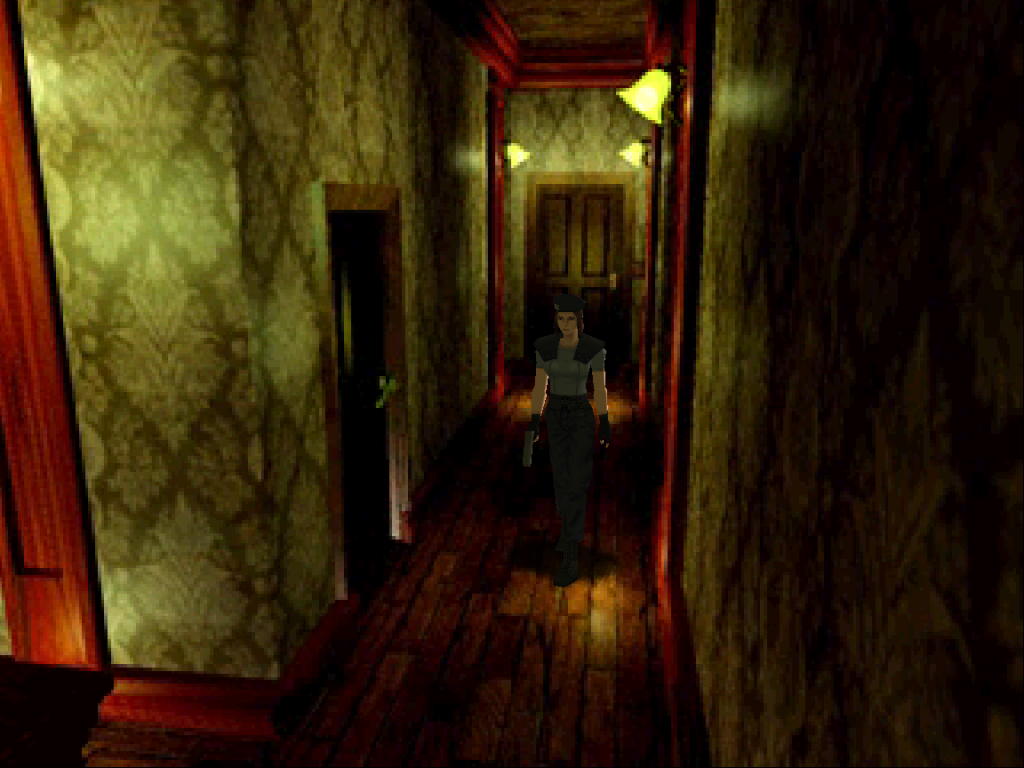

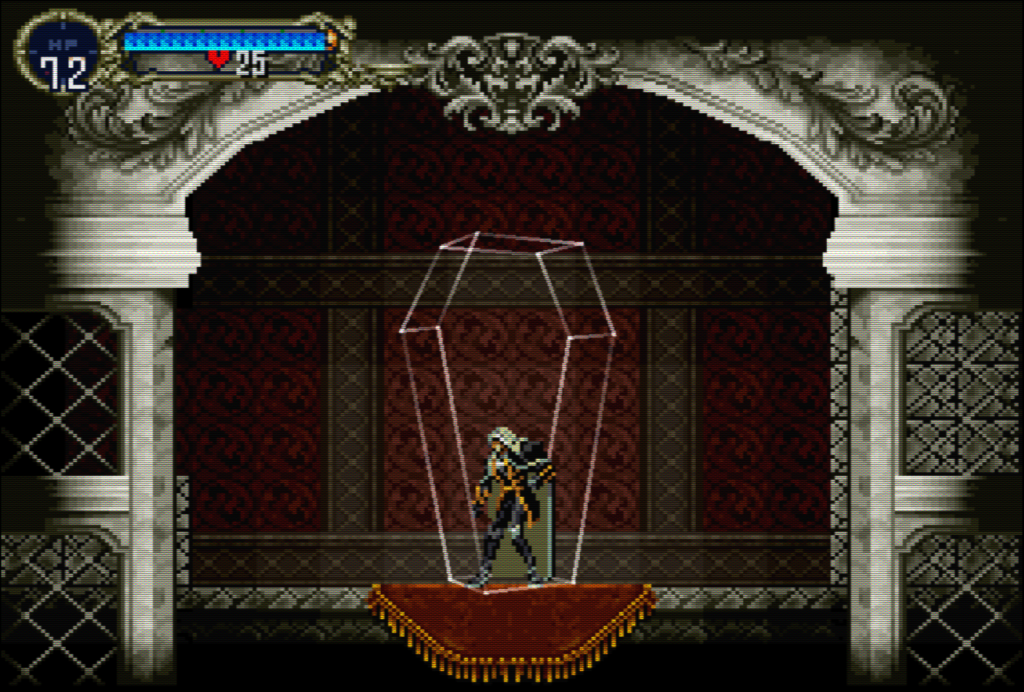

Castlevania: Symphony of the Night (1997, PlayStation/Saturn, Published by Konami)

Among the related games we discuss is Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, which boils the coffin’s place in vampire mythos to the purely mechanical—it’s how you save the game, once again conflating SAVE with SAFE. But the other reason we discuss it is for the other theme of the exhibition-

Uma: “The bell tower is maybe the central image of the show, the idea that there would be a place up at the top of this space, where you could wait, but at some point when you ring the bell, things would change. Ringing the bell draws attention to you, you can’t do it discreetly. You ring the bell and you can’t unring it”

That potentiality, the moment before the change.

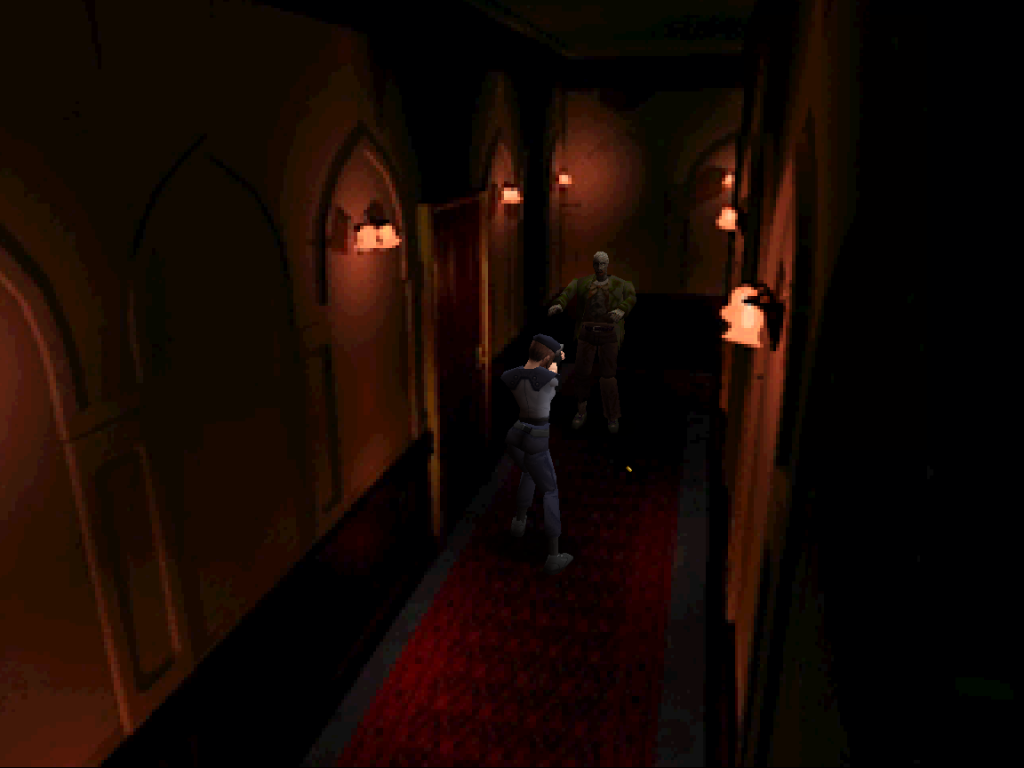

Castlevania: Symphony of the Night (1997, PlayStation/Saturn, Published by Konami)

To truly beat Symphony of the Night, one must invert the castle, rendering every room awkward to navigate, populating this once mastered space with harder bosses. A permanent change, but a necessary one to progress. In some ways I am glad to have caught the exhibition at this turning point, the moment before the bell rings, for I am also in a state of flux- the awkward walking chrysalis of early transition, with the maddening hope that soon I won’t be in this coffin.

Uma: “I played a lot of Resident Evil 2 (2019), in the police station I was really interested in the overlaps between the current use of the space and its previous life as a library and museum. That game is full of storage.”

Uma Breakdown, Earth A.D. 2 (2023). Installation view at FACT Liverpool. Photography by Rob Battersby

Liverpool is full of such spaces, a city fractured by bombardment and unfinished regeneration, my apartment an old warehouse, the Ropewalks a factory district. Their histories are not overwritten by their presents, existing instead in superposition.

The repeated presence of the Symbol of Chaos in Uma’s exhibit doesn’t feel out of place, itself an ever-repurposed image, from Michael Moorcock’s Elric, to Chaos Magic, to Warhammer 40k, and with various punk and anarchist organisations in between, a promise of some unknown future without a clean break from the past.

Uma: “Chaos is a place with a huge amount of potential, it’s where exciting things come from… my general philosophy of art is that I don’t want things to be fixed, I want them to be generative… I’m obsessed with cybernetics, having a system that will do something unpredictable further down the line… including shaking itself to pieces”

Uma Breakdown, Earth A.D. 2 (2023). FACT Liverpool. Photography: Rob Battersby

This goes some way to explain the prevalence of Warhammer’s ever transhuman imagery in the exhibit. Uma says that it came from an obsession with the Dreadnought, a robotic life support (“something like an iron lung”) for great warriors of the Adeptus Astartes, but in their vision it is not merely a grim method of forcing the dead (or dying) to keep fighting- it’s a form of care. Perhaps this second stage of the exhibit is our enclosure within the Dreadnought, a kind of cryogenic sleep before we can receive true care. I’m excited to see what’s next, for the exhibit-

Uma: “taking HRT, effectively running a different program through existing hardware, I am running a different voltage through this system and it’s making something else happen, and this makes me feel very secure in myself.”

-and to save some room for myself, too.

Earth A.D. 2 was on display at FACT Liverpool until the 28th of January, 2024, and was accompanied by digital game works that can be played here