Listen above for an immersive audio reading, read by Morgan and produced by Sammy Holden. Four of the cooling towers at Fiddler’s Ferry were demolished on 3rd December, 2023.

Today, I visit a ghost. Not of a person, though I’m sure many have died there. Not of a living thing at all, though now its surroundings are overgrown, flora and fauna clawing over the concrete like a John Wyndham novel.

Fiddler’s Ferry power station. To be demolished this year. Or the next. Strange ghost. Not even dead yet. Its heart weighed against a feather, caught in a purgatory of bureaucratic inertia. It will become an “employment site”, distinct from the current site of employment on the grounds. But it remains.

As a child, I thought it was a nuclear plant, clouds of steam glimpsed from the M6. Seeping into my brain, next to the recurring fear of acid rain. But no, coal, that fuel, that symbol, that fossil, simultaneously holding millions of years of history, and the ominous promise of history’s end. And Thatcher. An industry dead before I was born, but living in “the Northern Powerhouse” (add scare quotes as appropriate), it’s impossible to avoid the scars, mining towns left for dead, industry replaced by nothing…

Today, I visit a ghost. I should have worn black.

a ghost

seance

I am going to Widnes for the first time for no other purpose than to see a decommissioned power plant. The train burrows through the railway cutting, past bricked-up tunnels and a rotting house in the dark. The sky flickers between sunny and overcast like a chip shop fluorescent. I resist the urge to soundtrack the moment, to press this scenery into a mould.

And yet. Wires. Veins. I am following the Mersey, whose waters cooled the plant, the artery to the great concrete heart. The overhead wires feel almost reassuring- I’m a country girl at heart, and I prefer the sight of creaky wooden poles and their crisscrossing cables over fields to obscured wiring buried under my feet, unable to hear the gentle thrum of night electricity.

I first see them from the train. The eight cooling towers. I had expected them to loom. Each tower is 144 metres tall. The high chimney in the centre, a colossal cigarette stubbed out into the earth, is 200 metres. Taller than Godzilla, another reason they feel nuclear. But from here they barely peek out over a line of houses. Visible from miles away, yet hidden up close. As if they self-obscure.

There is a bus, but I miss it. Thus far you shall come and no further. Better on foot anyway. For all the benefits of public transport, there is still a separation, a distance unfelt, ephemera blurred in the windowpane. I follow the route on my phone, slightly too big Skechers with torn eyelets serving as a replacement for boots devoured by Dungeness shale, past gutted phone boxes, a house painted grey amongst the red, and… no one. Not since the park, one of few places I visited in Widnes where there seems absolutely no way to see the power plant, a concentration of roaming families, ice cream and a fun-fair, if in name only.

a monument

But then, not a soul. Just houses. Houses with people in, presumably, but not outside, miniature shadows caught through passing windows, displayed but shut away like dolls. The closest interaction with the living is a goose that attacks my camera. A cooling tower peeks behind the terraced terracotta houses. I ditch the map and follow that coal-fired north star.

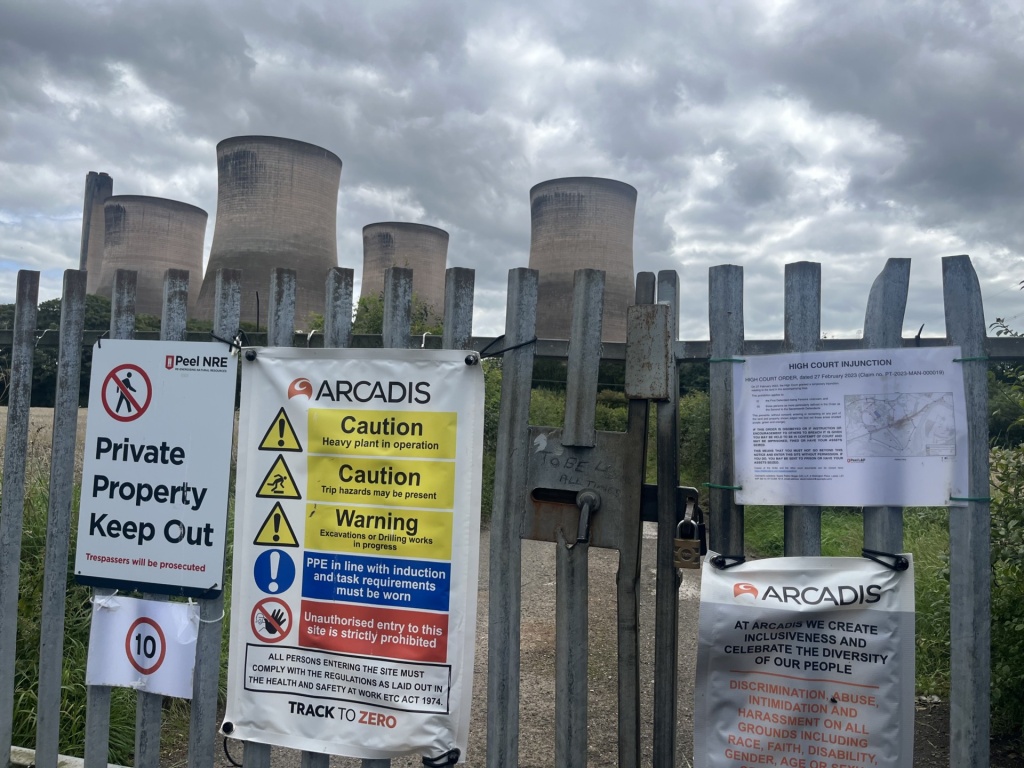

For a plant no longer in operation, it is buzzing with activity, considerably less alienated than the path I took to get there. I can’t actually go inside. Security is tight, perhaps tighter since folks were caught stealing cables. A stern warning reminding me not to take pictures through my camera lens. I take so many. None of them quite capture it though. Neither do my eyes, since it is impossible to find a vantage point that lets you truly see it. Snippets.

An abandoned roadside cafe offers polystyrene-cupped coffee and bacon butties in a time that might be a decade ago or just yesterday. Signs, so many signs, threatening reprisal from private security and reminding you of their Core Values of Inclusion. Rain-weathered A4 sheets with the sketched promise of the future Fiddlers Ferry, a document somehow less informative for reading it. And the towers, always hiding more behind them, and casting shadows across the microcosm of the inside, shuttling cars and white uniforms, ash lagoons viewed through a mess of wires and pipe.

but that isn’t what I see

not really

stood on the periphery

I don’t dare

I

cross over

my hands raised to the cooling towers

tuning into an alternative signal

I have arrived

I can’t go

inside, i am buffering in shaky YouTube footage

consoles and live wires spilling through the dark, in a window

sandwiched between comments of mourning workers

and algorithmically served hatespeech,

You Might Be Interested In a scapegoat,

clearly this failure can’t have come from

within the fields.

overgrown with grass and the ghosts

of celluloid children

sacrificed for public information films

that’s when I see

her

the devil of the North,

grinning in combat boots,

ready to flatten anything that isn’t a high-rise

but sat, bound in wires

pipes under her skin

(under my skin)

smog pouring from her mouth, under her eyes

(under my eyes)

death god silenced by private industry and lost futures

veins underground

the towers vents for this

death dreaming splatter demon

born in a centrifuge

demolish me with it

this monument

a northern ossuary

shards of me in the ground

a ghost from Dungeness haunting the grass

she’s barely breathing

undead as long as I’ve been alive

Albion,

rot creature chewing out its veins

waiting to be buried

in a mausoleum of ash and concrete

on the right side

of history.

I recollect myself in the local pub. The Eight Towers. One of those chain pubs that feels like Wetherspoons but isn’t, ales disconnected from taps in favour of mass production lagers. It’s quiet, the quiet that lets you overhear personal conversations that shouldn’t really be broadcasted.

I ask the bar staff if the name will remain once the plant is demolished. They’re not sure. It’s vague enough to remain without anyone questioning it, I suppose.

Even if it refers to a ghost.

a haunting

exorcism

The days after my visit are marked with shadows and dissociation. I would ponder my warehouse-converted apartment’s connections to dead industry if its thick brickwork wasn’t cooking my brain. I can’t sleep. Haunted by the weeping screaming thing slamming against the walls at the witching hour. A rattling and scratching of keys at a lock. The power plant visitation won’t stop bouncing around my head, and writing provides no catharsis. Haunted by phrases as I am by seagulls, and slamming doors on this melting night. Haunted. Maybe I really am.

And suddenly, in the dark, I think about Skelmersdale.

Part of the second wave of “New Towns”, the Skelmersdale Development Corporation and its extremely ominous logo transformed the mining town into an attempted utopia of low-cost housing, concrete walkways and a central mall by the name of “The Concourse”. That mall remains (even if the incredible Alan Boyson-designed pyramid does not), but within its grounds… a small demolition.

Skelmersdale

Nye Bevan pool, named after Aneurin Bevan, one of the architects of the NHS, has been earmarked for replacement by the end of 2023. I can’t help feeling sad about that. It’s where I learned to swim. Where my mother learned to swim. Its architecture looked dated to me even as a child, though I had no idea what those walls were meant to promise. Destroying this thing with his name attached, while our country destroys its health service, is an irony not lost on me. The types of things a power station seance make you think about in the middle of the night. My job is to find haunted things, to haunt things with meaning, or else be haunted until I can exorcise myself.

but there are things

you cannot exorcise

that you can never remove

neuroses tangled in shards of glass

I find myself there. I take a train, miss a bus, take another bus, listen to a podcast- pleasing normalcy after what has been several weeks of decay. My earlier preference for walking is annulled by this Designed for Pedestrians town that is, in practice, miles of roundabouts isolating a shopping mall.

Growing up, this was my nearest swimming pool, my nearest game shop, my nearest McDonalds, my nearest job centre… and yet this is my first time visiting Skem (as it’s more commonly known) for the sake of Skem. Like the towers of Fiddler’s Ferry, this concrete imposition felt like it had always been there, the more modern glass structures intruding on hallowed ground. The memory of Skem would likely remain an occasional anecdote to friends (did you know it has Europe’s largest roundabout?) had I never learnt of its pseudo-utopian ideals.

concrete edifices will not shield you

will not help you

will not save you

The Prospect of Skelmersdale is a documentary from 1971, and an album from 2016, the latter pilfering from the former. The film is a fascinating document, that spends as much time talking about the Skelmersdale of then as it does its imagined future.

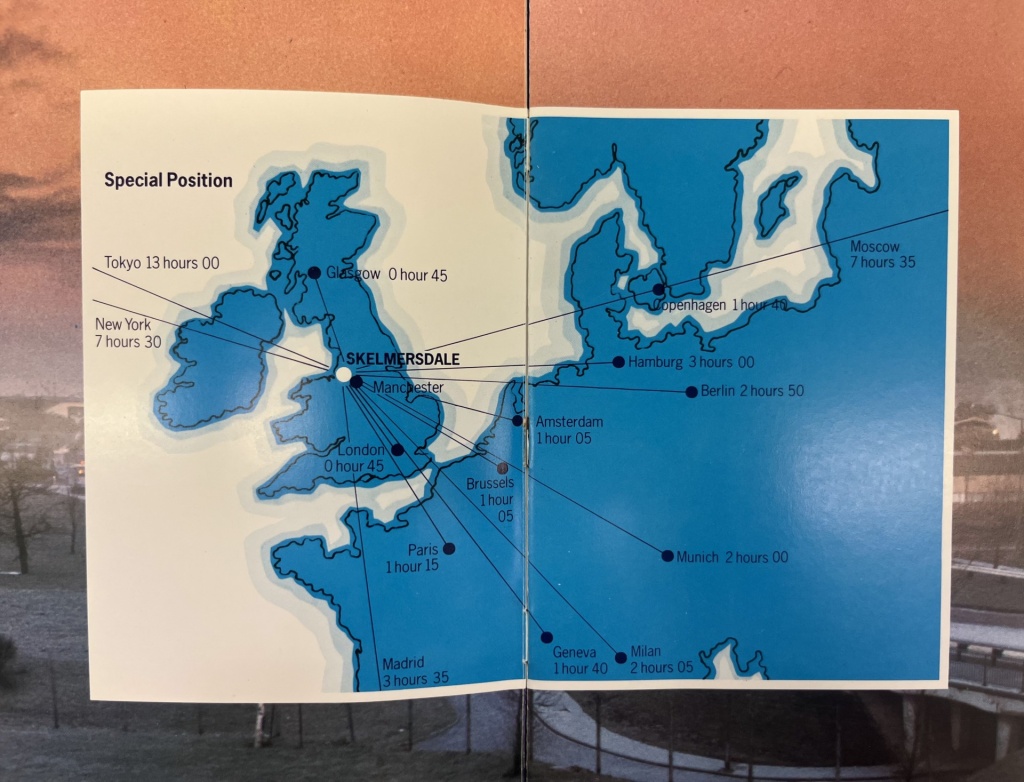

There are a number of cruel jokes made about Skem today, made easier by the gulf between its lofty ideals and punishing reality. It is bizarrely isolated, with the lack of train link, once purposeful in encouraging residents and businesses to put down roots, now blamed for its high unemployment rate.

centre of the world

The Aspiration Dispersal Field, a conspiracy theory that’s turned up in forum discussion and several newspapers, purports that this low social mobility is caused by a magnetic field broadcasted from Skem’s many roundabouts. That this story appears to originate on a website no longer accessible outside the Internet Archive, that promises “Nothing which is written in the website above actually happened in this universe” doesn’t seem to matter. Who wouldn’t prefer a narrative to make sense of it? That this Northern town was left to rot like all the others, based on a flawed premise that social democratic programmes could stop-

the rot seeping in

the plant cannot contain it

a ghost untethered

from psychogeography

I enter the library and rifle through the archives. “No one has looked at these in a long time.” A manilla envelope labelled GHOSTS / SKELMERSDALE. A guide to your new home, including the very Stepford feeling Welcoming Ladies and the bizarre emphasis that no pigeons or dogs are allowed. Pamphlet after pamphlet espousing the incredible commercial opportunities Skem’s central location holds, the same location that landed it the first Transcendental Meditation temple in Europe. When did the optimism die? I find a newspaper assuring that things will improve with the transition from the Development Corporation to the District Council, and that this will be the “Dawn of a new future.” Prospect describes the people of Skem as “sometimes confused by the luxury of a pleasant environment.” Did it last even a decade?

I stand outside Nye Bevan pool. Of course, the feeling is different from Fiddlers Ferry- this was a place designed for people, one that people still use, but it is also one I can’t help rendering in the past. Like the plant, allegedly it will be replaced. But given the pace of change in Skem, I can see the empty space lingering, caught between a demolished symbol and a future that is just always over the horizon.

and Albion will find its way here

and share with you its vision

of the No Future

premonition

The ghost has not left my skin. I still cannot see beyond the lingering grasp of Thatcher’s Britain, not helped by our government’s obsession with reanimating her spirit. You would think a country so obsessed with its past, of former glories crushing the world under its foot, would want to keep mausoleums, not destroy them.

An attempt was made to get Fiddler’s Ferry listed, as a significant symbol of 20th-century industry, however Historic England gave it “A Certificate of Immunity… as the Secretary of State does not intend to list this building…” That certificate ends in 2026, ensuring its protection from being protected, though I suppose I wouldn’t be surprised if it was still standing by then.

guarding ghosts

It’s a far cry from the treatment of Battersea Power Station, whose structure continues to dominate the Thames, though whether it being left to rot in uncertainty for decades only to finally become “one of London’s most exciting new neighbourhoods,” a gentrified hell of designer shops, upmarket chain restaurants, apartments and co-working spaces is better than annihilation is up for debate. This is the vision of the future, one somehow phonier than concrete utopianism. In Timothy Morton’s The Stuff of Life, he describes his dismay with the modern state of Battersea-

“Perhaps they’re not just obscuring the past. Perhaps they’re trying to cover up the future. Perhaps that’s what I actually don’t like about them. It’s not that they are getting in the way of something more authentic underneath. It’s that they’re preventing a future where luxury flats are no more from coming into view.”

Perhaps I will always be like this. Perhaps Britain will always be like this. It is strange to be a person your government would like dead. Maybe that’s why I’m so morbid, obsessed with old things, dead things, red flags no longer flying here. I write this staring out over the Liverpool skyline, seagulls squawking, aerials fluttering in the breeze, echoing tannoy from Liverpool Lime Street. Architecture intensely fractured between before and after the flattening of German bombs.

I can’t escape the 1970s. Neither can Britain. Smash these mausoleums and their spirits will go into the aether. But it isn’t just the power plants and swimming pools that are haunted, it is in the soil, blood-soaked and pumping out miasma, a Leviathan striding across a dead island, and though a generation will note the absence of Fiddler’s Ferry in the skyline,

if they look closely

they will still see

the clouds