Recently the video game industry, and adjacent industries like game and tech journalism, have become known for their ruthless “layoff culture”. For instance, last year one such media outlet, Gizmodo laid off dozens of its writers, only to replace them with AI bots that resulted in disappointing and error-filled article writing.

With massive amounts of people being laid off at various levels, developers and directors will vaguely cite the need to remain competitive, and curb projected losses due to waning the COVID-19 lockdown boom. Alongside the generative journalism market, such developers have been putting their hopes of remaining productive despite layoffs by replacing the lost labour with the output of AI tools.

a precarious industry

In most instances, these tools and software were not meant to wholesale replace the skilled human specialists on AAA projects, or so was claimed by industry heads throughout 2023. But in 2024 this position seems to have been abandoned by big companies like Ubisoft (which is experimenting with several AI tools for writing and voice acting), CD Projekt RED (who laid off 9 percent of its staff in 2023 and is looking into AI tools to develop the next Witcher title) and Keywords.

The last of these recently reported a failed project to create an entire 2-D game, called “Project Ava”, implementing over 400 generative AI tools. Keywords, known as a UK-based global service provider which contributed to games like Baldur’s Gate III as well as Alan Wake II and Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom, reported that, as the more progressive North American companies and professionals have, AI cannot replace human talent. Though, unwilling to completely abandon the idea, Keywords did see evidence for AI tools being able to “simplify or accelerate certain processes” in game design.

This is a climate similarly affecting voice over talent in the games industry, which voiced uproar recently over a deal pushed, unbeknownst to those affected, through the American union SAG-AFTRA (Screen Actors Guild – American Federation of Television and Radio Artists). Early this year, SAG-AFTRA announced that they would be partnering with AI company Replica, which creates digital replicas of voice actors. While major news outlets like BBC, Forbes and The Mary Sue have covered the deal, there has been little media discussion of the implications of creating AI replicas of voice actors, and how this would devalue the work of those voice actors, who aren’t as recognizable as the “celebrity-turned-voice-actor” often used in popular animated movies, (or the recent games of Hideo Kojima).

The Congressional Voice

Vera Wylde, host of the geek and pop culture commentary YouTube channel Council of Geeks, offered an early and astute observation of SAG-AFTRA’s deal and the legitimate concerns voice actors had regarding it. She notes that despite there being ethical clauses to ensure voice actors are duly compensated and can opt-out of having their digital voice replica being used in perpetuity, there’s still the matter of AAA game studios preferring to use cheap replicas of Hollywood actors over lesser known voice actors. She also notes that there’s always the potential for voice actors feeling forced to sign contracts that require digital replicas, for fear of losing their livelihoods.

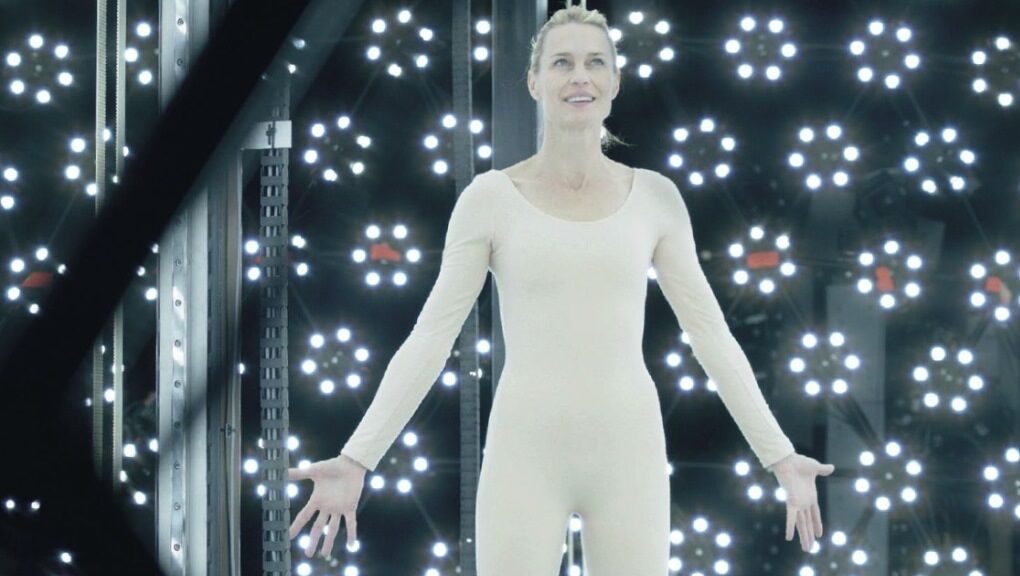

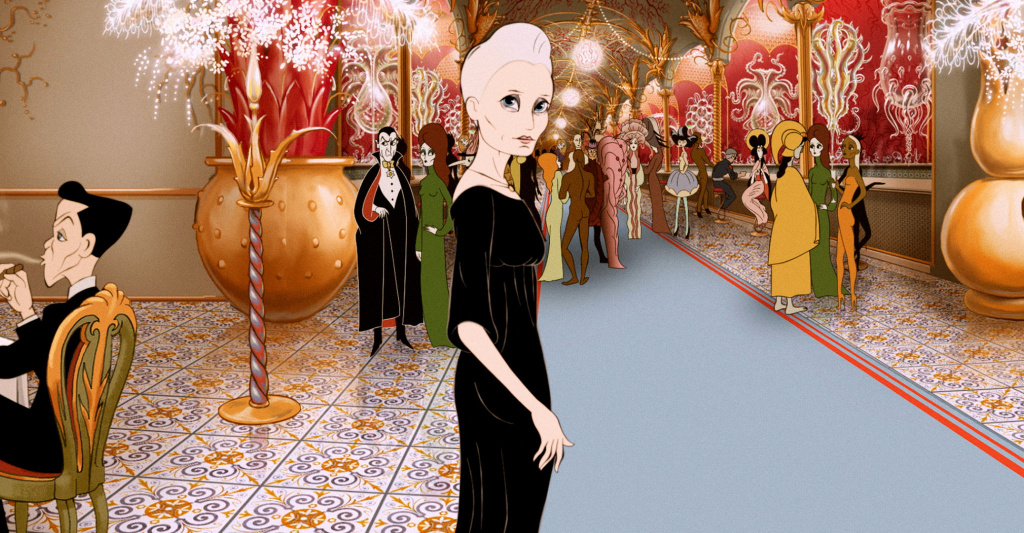

Ari Folman’s The Congress (2013) comes to mind here, which offers a useful framework for thinking about the extreme possibilities of digital replicas. The film reimagines Stanislaw Lem’s 1971 novella The Futurological Congress, illustrating a world consumed by a Bacchanalian spectacle akin to Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights. Performers like Robin Wright, playing a version of herself in the film, struggle to find meaning as they sign away the rest of their career to a digital replica of themselves who will perform in whatever film human actors would have had the choice to refuse.

The Congress (2013, Dir. Ari Folman)

Folman used green screen technology to paint over actors, in the classic 2-D animated style of early 20th century animation, to create the warped mirror world (one filled with people styling themselves as their favourite actors or fictional characters) of the titular Congress Wright attends. In the film Wright feels forced into signing the fatalistic contract because the studio she works for, Miramount, lets her know that industry heads have already decided that this is the future of film, while she, a single mom, cares for a son with a rare and progressively degenerative disease.

Black Mirror has explored the topics of Generative AI and AI replicas as well, in episodes like “Joan is Awful” and “Be Right Back”, respectively. Yet unlike The Congress, Black Mirror has been criticised for not locating its antagonists in the human establishments willing to replace people with so-called bleeding edge technology. After all, CD Projekt RED’s surprisingly ethical use of AI to recreate a late Cyberpunk 2077 actor’s performance is not the exact problem—it’s their culling of staff, likely in favour of AI tools handling Witcher 3’s development, that is.

The Congress (2013, Dir. Ari Folman)

The Replicant Voice

Returning to the SAG-AFTRA announcement, its problematic communication of the matter is an important aspect of how such trends of power follow fictions. The union claimed that the deal was “unanimously approved by the Interactive Media Agreement Negotiating Committee which is comprised of voice actors working in the video game industry”. This is also the vague language of the actual agreement outlined in Replica Studios’ F.A.Q. and other legal documents, which can be accessed from SAG-AFTRA’s website. Replica claims that voice actors were actively involved in the bargaining process and “met with key executives of Replica Studios” before being approved by the union’s Executive Committee.

Voice over veterans, like Steve Blum, took to social media to decry SAG-AFTRA’s deal and the e-mail which was sent out to members using similar language to the eventual agreement documentation. “Nobody in our community approved this that I know of,” was the most notable of Blum’s online reactions to this announcement.

SAG-AFTRA sticks by its narrative that voice actors were involved in the bargaining process, which has been a worrisome claim, considering how much of the voice acting community is outraged by this deal. AI has been one of the chief concerns for these performers, and was unaddressed by a post-strike agreement reached in 2017 with video game companies, which won them a sliding scale of bonus payments as well as better transparency for what roles on offer require, and an employer commitment to finding ways to reduce vocal stress.

Somewhat ironically, SAG-AFTRA president Fran Drescher characterized the effects of devaluation on workers due to digitization as something “happening across all fields of labour” in her speech given last year. This speech was given when the union voted nearly unanimously to go on strike and drew a binary line between workers who were “in jeopardy of being replaced by machines and big business” who prioritised profit over the security of their families. Yet with this deal between the union and Replica, this messaging points towards hypocritical stratification between film and tv actors protections and those of voice actors. Duncan Crabtree-Ireland, the union’s chief negotiator, signed the deal with Replica two months after joining the picket line in 2023, according to the BBC. He believes the deal was fair and is in fact protecting voice actors’ rights.

The Congress (2013, Dir. Ari Folman)

The Historical Voice

Anna Brisbin, a video game voice actress who hosts YouTube channel Brizzy Voices, uses her platform to educate the curious, and those looking to break into the competitive industry. In 2022 she researched and produced a three-part series about the North American history of voice over. Brisbin argues that the first voice over artists were an estimated 18 uncredited women who provided their voices for Thomas Edison’s failed talking doll product in 1890. Although they are known as the first hired recording voice artists and the first women to be recorded as well, they remain unnamed. Instead the official credit for first voice over performance is usually attributed to the father of voice-transmitted radio, Reginald Fessenden.

Throughout voice over history, artists often struggled for recognition, compensation, or both. In some cases, as with Betty Boop’s actresses in the 30s, there were messy court cases involving Helen Kane, who claimed that her voice and particularly her singing style were being stolen. While this was not necessarily untrue, as Boop’s first actress Margie Hines was known for her Helen Kane impersonations, the court case revealed that Kane had no claim to her style of performance being unique, because, she was likely inspired by the style of child cabaret performer Esther Lee Jones.

In addition to the above, iconic performers such as Adriana Caselotti and Mel Blanc, “The Man of 1,000 voices”, who provided voices to characters like Disney’s Snow White, and Looney Tunes’ Bugs Bunny were also undervalued and often uncredited. Caselotti was even barred from the premiere of the movie she starred in, and had to sneak in with fellow performer Harry Stockwell, who played Prince Charming. Walt Disney himself also kept her from pursuing any further credited voice work as he didn’t want to “spoil the illusion of Snow White.”

Tying this to the current digital replica deal, there seems to be a long history of voice over performers not only being devalued, but viewed as a personal brand to be extracted from and exploited.

This is a particularly North American phenomenon, and vastly different to the culture around animation industries in Japan for instance, where voice actors, or Seiyuu, are regarded in a similar manner to Hollywood film and TV celebrities.

Today we have access to resources like IMDB and ‘Behind the Voice Actors’ to keep credits at least somewhat more straightforward than in the early days of cartoon voice over, and credits have become more or less standardized. But, compensation is still hotly debated by stakeholders in the game industry regarding voice acting. During the 2016-2017 video game voice actor strike mentioned above Scott Witlin, the lawyer representing video game companies claimed that despite being “top craftsmen in their field” they made up “less than one tenth of 1 percent” of video game production work and paying them according to a different system than the other 99.9 percent of people in production would result in a problematic situation for the industry.

The Human Voice

Important to note is that while there is cause for concern regarding how the SAG-AFTRA and Replica deal will be implemented, there is already talk of generative AI tools peaking. People are often very aware of the lacking emotional verisimilitude of AI voices, despite how advanced the technology has become.

Samantha Béart, the actress who played Karlach, the Tiefling barbarian with a fiery golden heart from Baldur’s Gate III, recently commented on AI replacing human talent in games, during a talk with narrative designer Alexa Ray Corriea. She said that despite the games industry being decimated by speculation of overemployment during COVID-19 lockdowns and sweeping adoption of AI tools that “people really love human made games” and that if there was an argument in favour of that it would certainly be Baldur’s Gate III.

Actors at Larian Studios making Baldur’s Gate III

The title, which has won multiple awards, and earned Béart and colleagues Amelia Tyler and Neil Newbon nominations for Best Performance BAFTAs, notably employed over 240 voice actors.

At times like these, it is difficult not to think of works like The Congress, which reflect Byung-chul Han’s argument, in his essay Non-Things, that excessive digitization “de-reifies and disembodies the world.”

We should be attentive then when a union, that’s supposed to be speaking for voice over performers, instead makes a deal that effectively speaks over its own distressed members, and has the potential to render them redundant