As creative technologists, we might be technologically savvy enough to protect our individual data online, but is it up to individuals to make mindful, informed choices about the collection and use of their personal data? Or should we be striving for a society where we don’t need to be constantly thinking about our data and the implications of giving it up?

A lot of activism around data privacy involves training individuals to protect themselves using online tools. This form of activism, while arguably empowering and useful, reinforces a model where everyone must be an expert to have protections for their privacy.

In this illustrated article, we highlight actions that might encourage a model more similar to health food standards, where we don’t have to check what procedures have been followed for each thing we eat. And we ask what creative technologists can do as a community, both to encourage the ethical use of personal data in creative technologies, and to resist unethical data practices in the broader technology community.

Setting the Scene: The Fight for Rights in the Time of Brexit and COVID-19

Illustrations by Stacey Olika

Data rights laws protect us in relation to the collection, ownership and use of our personal data. They are there to protect us from governments, private companies, and individuals abusing our data: from targeted advertisements to biased algorithms and unwanted surveillance. However, in the soup of emerging technologies, Brexit and a global pandemic, data rights policy in the UK has reached a critical boiling point. Tech companies and data protection laws don’t always get on. Money can be made from personal data, creating a friction between the rights of individuals to own and control their data, and the businesses that might profit from that data.

The opportunity to profit from data creates a conflict for our business-orientated government, which is currently required to uphold GDPR – the General Data Protection Legislation – an EU law on data protection and privacy. With Brexit coming, new trade deals are being negotiated globally, including with the USA. It looks like the measures in our free trade agreement with America could include implications for how the internet is regulated in the UK, as well as watered-down privacy protections to keep American tech giants happy.

Evidence that our data protection laws may be in danger isn’t a new phenomenon. The UK’s data protection regulator, the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), have been lax in upholding complaints made about AdTech for sometime. But Brexit negotiations, plus the pandemic, have exacerbated their lack of regulation. From the first emergency measures, Matt Hancock hinted that data protection laws no longer applied in the state of emergency and the ICO essentially paused their regulation, leading to a track-and-trace system being rolled out without even having a legally-required Data Protection Impact Assessment. This lack of oversight has led to advocacy groups, such as Open Rights Group (ORG), rather than the regulator, challenging the government and private companies for breaking the law in recent months.

What can be done? Working together for better data rights

Step 1: Raise Public Awareness

Use creative technologies to highlight and communicate the repercussions of unethical data use.

While striving for a world where everyone’s an expert might not be feasible (or even ideal), more awareness is never a bad thing. Public awareness is an important tool in lobbying for policy change and drafting democratic solutions. Creative technologies can be used both to educate people about existing issues, and help them explore what influences how they feel about the collection and use of their personal data.

A dramatic example of the power of public awareness is Edward Snowden. When he blew the whistle on global surveillance programmes back in 2013, he provided insights that activists across the globe have been using ever since to exert pressure on governments. Similarly (but on a different scale), the Bristol-based co-operative newspaper, The Bristol Cable, investigated the police’s use of mass mobile phone spying technology. Their findings were successfully used in a legal battle that resulted in British police being forced to release more information about their use of this technology.

Step 2: Develop a Community Code of Practice

Many conversations around data protection boil down to what is lawful, but it is important to remember that individuals and communities can agree to uphold principles and practices that go further than what the law dictates.

Agreeing on and democratically adopting a code of practice as a community helps normalise higher standards and practices. By setting an example of the kind of data practices you want to see in the world through your own community, you can inspire other communities and organisations to follow suit. It may even make these better set of practices more feasible for governments to adopt in future regulation changes.

Step 3: Engage with Data Rights Advocacy Groups

Advocacy groups like Open Rights Group (ORG) are constantly monitoring developments in the law, government, and practices around our data online. Recently they have been upholding existing laws through legal action when the official regulator failed to do so.

You can join ORG as a member, attend events run by their local groups, and take part in their regular actions to combat unethical or unlawful online data practices.

Step 4: Explore and Champion New and Existing Models of Data Ownership

Through data collectivism, cooperatives and unions, people are experimenting with different ways of working together to wrest back control of their data from big tech.

Here are some examples of the most interesting and innovative models out there, and the people and projects leading the way.

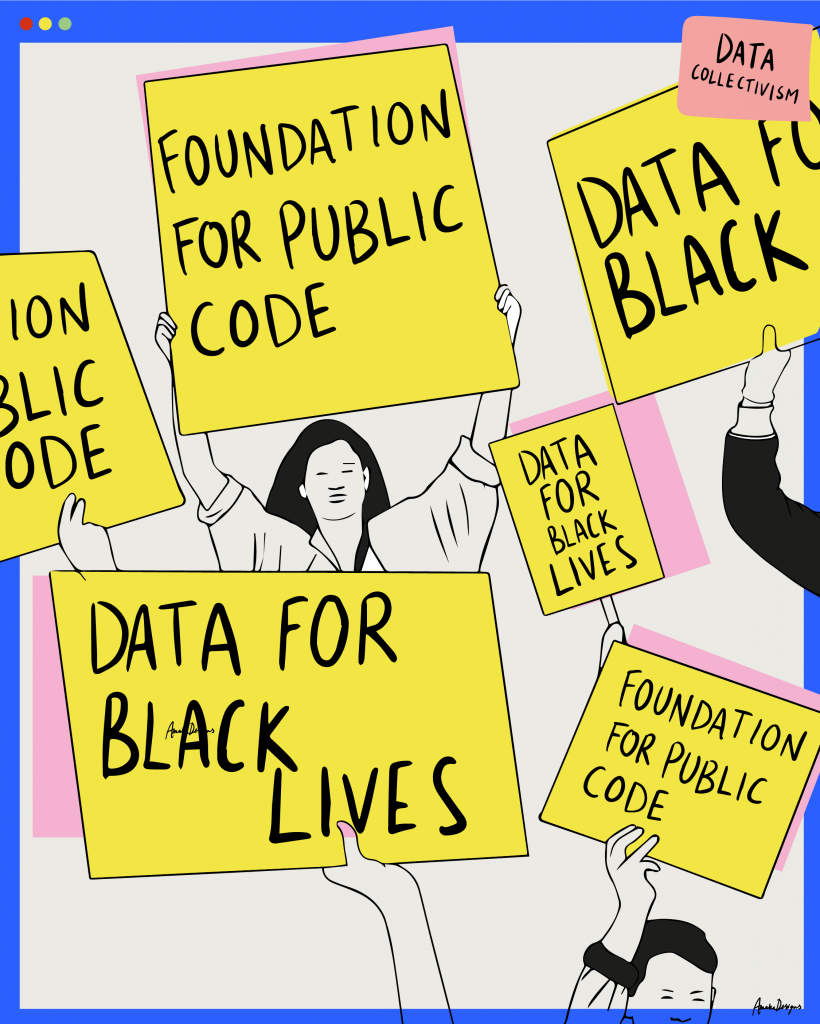

Data Collectivism

As the name suggests, data collectivism is about working together as a group towards a shared aim in data rights.

Data for Black Lives (USA, established 2016) is a movement of activists, organisers, and mathematicians committed to the mission of using data science to create concrete and measurable change in the lives of Black people. The network aims to put tools like statistical modelling, data visualisation, and crowd-sourcing in the hands of of communities in order to fight bias, build progressive movements, and promote civic engagement. They connect communities through D4BL (Data for Black Lives) Hubs in cities across the USA, as well as other meetings and events online and offline, working at a community level to change local and national public policy, educate people about the impact of algorithms on their lives, and promote the accessibility of data.

The Foundation for Public Code (Netherlands, established 2019) works with public organisations to create ‘public code’, i.e. open source software for public use. Through a process they call “codebase stewardship”, they ensure that the open source codebases are trustworthy, usable and sustainable. Their aims are for public organisations to be more successful: to foster and build sustainable communities, and create a thriving public open source ecosystem.

Data Unions and Cooperatives

A data union allows people to earn money by selling their data. It is a form of data economy that allows the individual to decide which data they wish to make accessible, and decide whether or not to make this data available to retail.

The idea behind a data cooperative is much like any other kind of worker co-op: it is a membership organisation where members collectively own and share their data for mutual benefit.

Both unions and cooperatives are ways of rebalancing the asymmetric relationship between data subjects (people with personal data) and data users (people who use data to develop services and products).

There are lots of examples of data unions and data cooperatives out there, but here are some you might not have heard of:

Controlr (UK, work in progress, established 2020) is a new data union focused on Black and marginalised people. It aims to use its alternative business model to democratise access to data. Instead of the idealised user being white, male and millennial, Controlr is being developed with a focus on marginalised people from the outset – all community-building, marketing, promotion, and educational activities are dedicated to working with people normally marginalised by new tech initiatives.

Controlr combines the practical benefits of a data union – which uses decentralised technology and cryptocurrencies to make micro-payments for data – with a political drive to rebalance the bias and discrimination inherent in much of today’s data and technology products. While there are already data unions out there, they do not penetrate the social consciousness of the masses. Controlr creator Tracey Bowen says this is a product problem: “The access isn’t that great…joining can be difficult…what they are missing out on is making it easier for people who are not data savvy.”

Next steps for Bowen include working to ensure Contolr is technically practical, as well as working with Black and marginalised communities to beta test the product over the next year.

Worker Info Exchange (UK, established 2018) is a non profit organisation that helps workers access and gain insight from data collected from them at work, usually by smartphone. The Worker Info Exchange generally works with gig economy workers, such as Uber drivers and Deliveroo riders. They use the pooled data of workers to demand a better deal in the workplace. They are currently supporting a case in the courts against the ‘robo-firing’ of Uber drivers: where Uber use an algorithm to make decisions about fraudulent activity and the subsequent ‘deactivation’ of drivers.

Data Workers Union (international, established 2017) is a speculative artistic project that encourages people to establish a data workers union, “to end the limitless exploitation of our production of data and to fight to gain control of its ownership”. The website outlines a series of data rights principles that, for example, support collective data ownership and data cooperativism, and call for the end of ‘digital colonialism’ and exploration of data for economic, military or political purposes. They also call for a data tax and data basic income. The Data Workers Unions organise projects, assemblies, workshops and talks.

LabGov, the LABoratory for the GOVernance of the City as a Commons (international, established 2011), is an international network of researchers who focus on the collaborative management of city spaces and resources. Initiated in 2011 by Christian Iaione (Professor of Urban Law and Policy) and Sheila Foster (Professor of Law and Public Policy) to put their ideas of urban commoning into practice, LabGov has collated data on collaborative urban resource management from over 130 cities and over 400 commons-based projects and urban policies. They created the Co-City Protocol, a guide to encourage communities, policy makers and researchers to work together on co-governance experiments, has been tested in the Italian cities of Battipaglia, Mantua, Reggio Emilia, and Rome, as well New York and Amsterdam, San Jose, Sao Paolo and Accra.

LabGov – The Laboratory for the Governance of the City as a Commons

Data Sovereignty

Given that we’re in a world where legislated data rights aren’t necessarily in line with our values, it makes sense to empower ourselves individually while fighting for a world where we don’t need to. So with this in in mind, we wanted to finish off with some tools for protecting your data online, from DECODE.

DECODE Ecosystem (Europe-based, established 2017) provides tools for citizens’ data sovereignty. Developed as a response to people’s concerns about the loss of control over their personal data over the Internet, DECODE provides decentralised, privacy-enhancing and rights-preserving tools to give back data sovereignty to people. DECODE developed a series of applications to show how data as a common infrastructure could generate public value so that communities can take advantage of the collective value of their data. Apps include Decode OS (private peer-to-peer network behind the project), Zenroom (smart contracts engine, powering Decode), Decode App (provides anonymous authentication for digital democracy applications and can be easily customised) and BarcelonaNow (interactive dashboard to explore, interpret and share urban data).