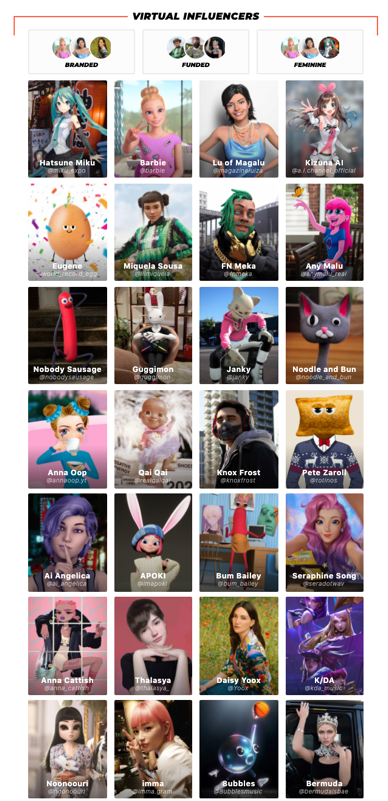

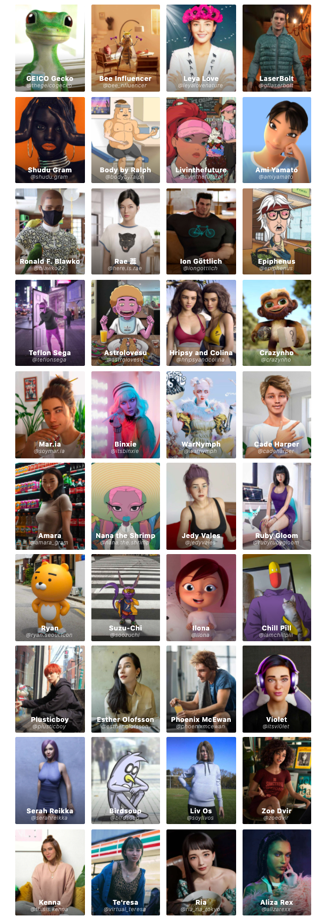

In June 2018, TIME magazine named Miquela Souza one of the 25 most influential people on the internet, despite the fact she is not a real person. Created in 2016, Miquela is a computer-generated virtual influencer, the most high-profile and successful of her kind to date with three million Instagram followers and 1,010 posts.

Lil Miquela’s Instagram post on February 25 2021

A social influencer is “a key individual with an extensive network of contacts, who plays an active role in shaping the opinions of others within some topic area, typically through their expertise, popularity, or reputation”, according to Oxford Reference. Virtual influencers often form a sub-group of social media influencers, and live or exist purely on social media platforms for the entirety of their digital lives.

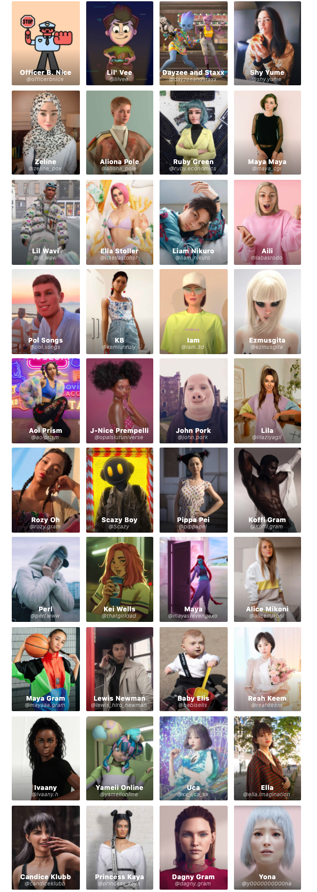

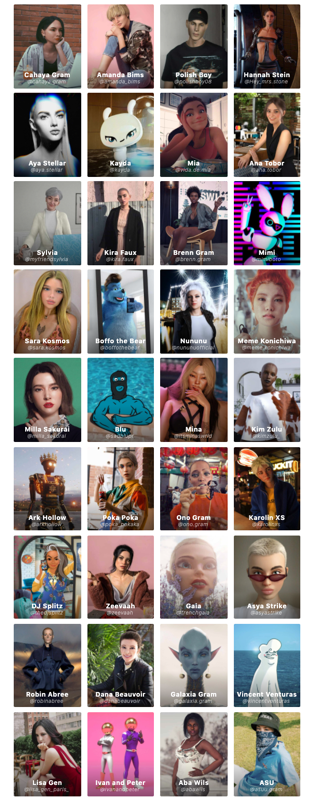

Lil Miquela, Shudu and Knox Frost

From Downey, California, Lil Miquela is a 19-year-old, Taurus, half-Brazilian and half-Spanish avatar pursuing her music dreams in Los Angeles.

Miquela is the project of Brud, founded by Trevor McFedries and Sara DeCou. Before creating Brud – a creative agency specialising in robotics, artificial intelligence and media businesses – McFedries previously worked in the music, film, television and tech industries. Sara DeCou was listed on Forbes’ 30 Under 30 list for consumer technology in 2019, though she remains cryptic about her occupational history prior to founding Brud.

In January 2019, Brud was worth upwards of $125m after a round of financing led by Spark Capital, with investors seeking part of the ‘avatar’ action.

OnBuy estimated the highest earning virtual influencers in 2020

In line with the growth of the spending power of Generation Z, the global influencer market could rise to $15bn in the next couple of years. Because COVID-19 has led to the cancellation of product launches, physical events and sponsored travel, some human influencers saw revenue streams dry up. By contrast, according to OnBuy, a UK-based online marketplace, Lil Miquela will have made an estimated $11.7m for her creators in 2020.

Writing in The Nation, Emmeline Clein criticises Miquela’s qualifications for her reputation, claiming that her existence is a contradiction. Clein describes an Instagram post where Miquela sits atop one of two washer-dryer sets, having just donated to a women’s shelter using the proceeds from her merchandise sales. Clein refers to the donation of a portion of the profits – to an “uncontroversial social justice cause” – as textbook ‘philanthrocapitalism’, which she declares is “part of a larger paradigm of corporate social responsibility essential to rationalizing [sic] the morality of capitalism, and in doing so allowing the entrenchment of inequality”.

Clein continues: “The easy blending of promotion and principle […] reduces social justice to a predilection used to reveal personality in a celebrity profile, as flimsy as personal style. This is perfect for huge corporations, which would like the status quo of capitalism maintained, but definitely don’t mind a few Instagram posts about diversity.”

Inspired by a Barbie doll called Princess of South Africa, Shudu, is regarded as the world’s first virtual supermodel, with an Instagram following of over 214,000. British fashion photographer Cameron-James Wilson created Shudu in 2017 to promote diversity in the modelling world. He creates evocative and engaging Instagram posts: from rich tribal imagery to modern collaborations and powerful pop-cultural characterisations.

In an interview published in Harper’s Bazaar, Cameron-James Wilson comments: “[Shudu] represents a lot of the real models of today. There’s a big kind of movement with dark skin models, so she represents them and is inspired by them.” Shudo has been praised by some but has also stoked controversy, as she is also seen as “a fake rendering of a woman of colour taking up space in an industry where real women of colour already struggle to find a platform”.

In 2020, the World Health Organization enlisted a fake human to help place accurate, vetted information about COVID-19 in front of millennials and Generation Z. They sponsored Knox Frost, a digital rendering of a 20-year-old guy from Atlanta, to make several posts about life in quarantine.

US-based Truth in Advertising (TINA), a non-profit organisation dedicated to empowering consumers to protect themselves against false and deceptive marketing, insist that virtual influencers are not subject to the same level of scrutiny as human influencers. TINA are pushing for this to change.

TINA recommend expanding the definition of ‘endorsement’ to specifically include virtual influencers. Furthermore, they recommend that any material connection between the creator and/or owner of the virtual influencer and the promoted brand must be disclosed. They also insist that virtual influencers should not promote products that are meant to impact or change a human’s appearance, or that they cannot genuinely use, such as the application of makeup. Finally, TINA say, virtual influencers must disclose that they are bots in all promotional posts. Virtual influencers should not go two years before being ‘outed’, as was the case with Lil Miquela.

Behind the Scenes, as a Creator

Creating Evie

Evie Digigram was conceived as a way to support my dissertation research looking at the social impact of virtual influencers. She helped me explore the culture of virtual influencers from within the online community of these influencers and their creators.

Using a suite of character creation and animation tools, artificial intelligence-driven software processed the photo of a human, Ashleigh, and rendered her on to a humanoid 3D character model. Further sculpting and customisation was applied.

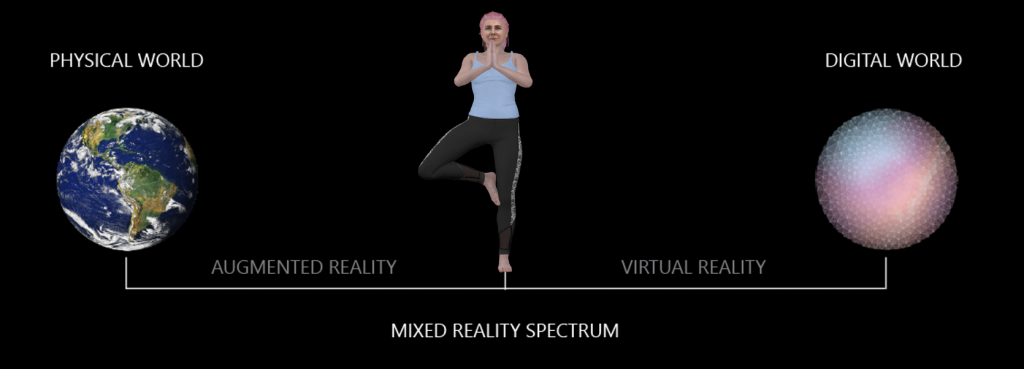

The character creation and animation software generated a fully-rigged character that can be clothed and animated using facial gesture tools, text-to-speech, and lip-sync technology. These characters can be 4K for film quality, or low poly for use in games, VR, and AR.

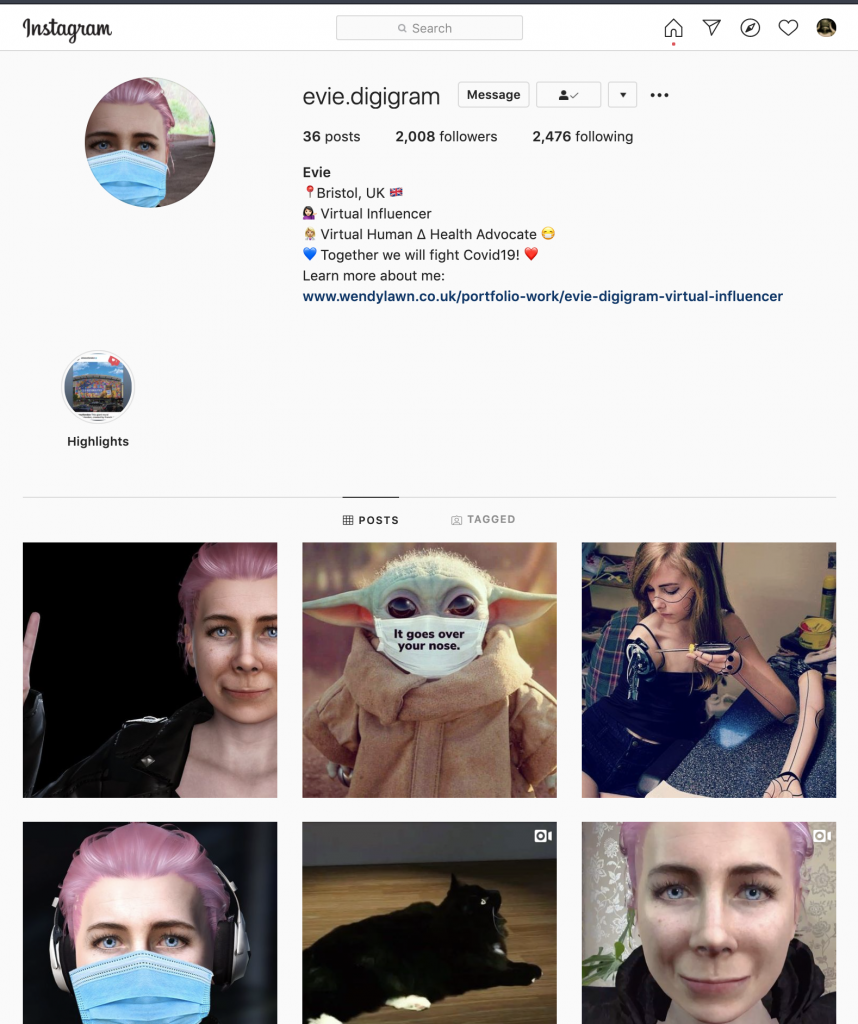

Evie Digigram’s Instagram account

Evie.Digigram’s Instagram account was registered on October 2 2020. Her followers peaked at over 2,000 in December 2020. Through social media channels, the Evie project focussed on creating a virtual influencer that could socially engage followers during the COVID-19 pandemic: she talked about wearing a mask, insisting her followers followed suit; observed safe distancing; and relayed news about lockdown, the COVID-19 vaccine, mental health issues, self-care, staying home, and staying safe.

Evie is a fierce social commentator. She communicates about her daily life and activities, and reflects realistic human moods, with both highs and lows. She promotes a range of issues including the climate emergency and veganism. She advocates for those with mental health issues and supports social inclusion and gender equality. She has not self-identified with ethnicity, disability or sexuality.

Evie’s Story

Evie Digigram was a cathartic project negating some of the impact of bereavement at the time of the death of my sister, although this was not openly discussed on Instagram. Evie took the likeness of my niece, Ashleigh, whose mother, my sister, had passed away in June 2020, after a six-month battle with a brain tumour.

A few months before this project was conceived, Ashleigh had been in the final year of her undergraduate nursing degree at UWE Bristol, on placement at the local hospital, and then seconded to join the NHS effort to treat COVID-19. Before qualifying as a nurse, she had to deal with the death of COVID-19 patients first-hand.

One message I received from Ashleigh in April 2020 described a patient’s death in real time. The patient had been placed on a bed pan and given the dignity of a few minutes privacy. But five minutes later, Ashleigh returned to find the patient had died. I could tell she was in shock. This was one of the first of many traumatic deaths that were to follow. Like many on the NHS on the front line, Ashleigh found the mentality of anti-mask protestors and pandemic conspiracy theorists devastating and disheartening. After long shifts on hospital wards, their faces bruised and sore from wearing PPE masks, NHS workers were emotionally exhausted, and found the negativity crushing. Yet they persist.

Initially, Evie was going to tell this story, with her persona built around the same life pattern. But on considering the ethical implications of whether this was right to share publicly without any sugar-coating or support for people that found it traumatic, I questioned whether Instagram was the correct platform, and so much of it went unsaid.

Infiltrating the World of Virtual Influencers via Evie

In 2020, society was at a burgeoning transition point where virtual characters, particularly virtual influencers, became extremely topical. By creating Evie, it became possible to follow virtual influencer developments and network with their creators as events happened.

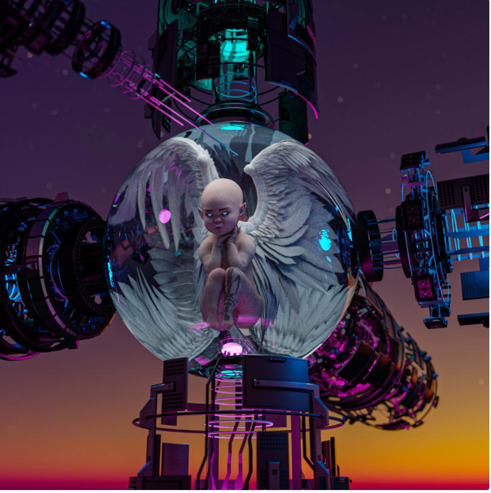

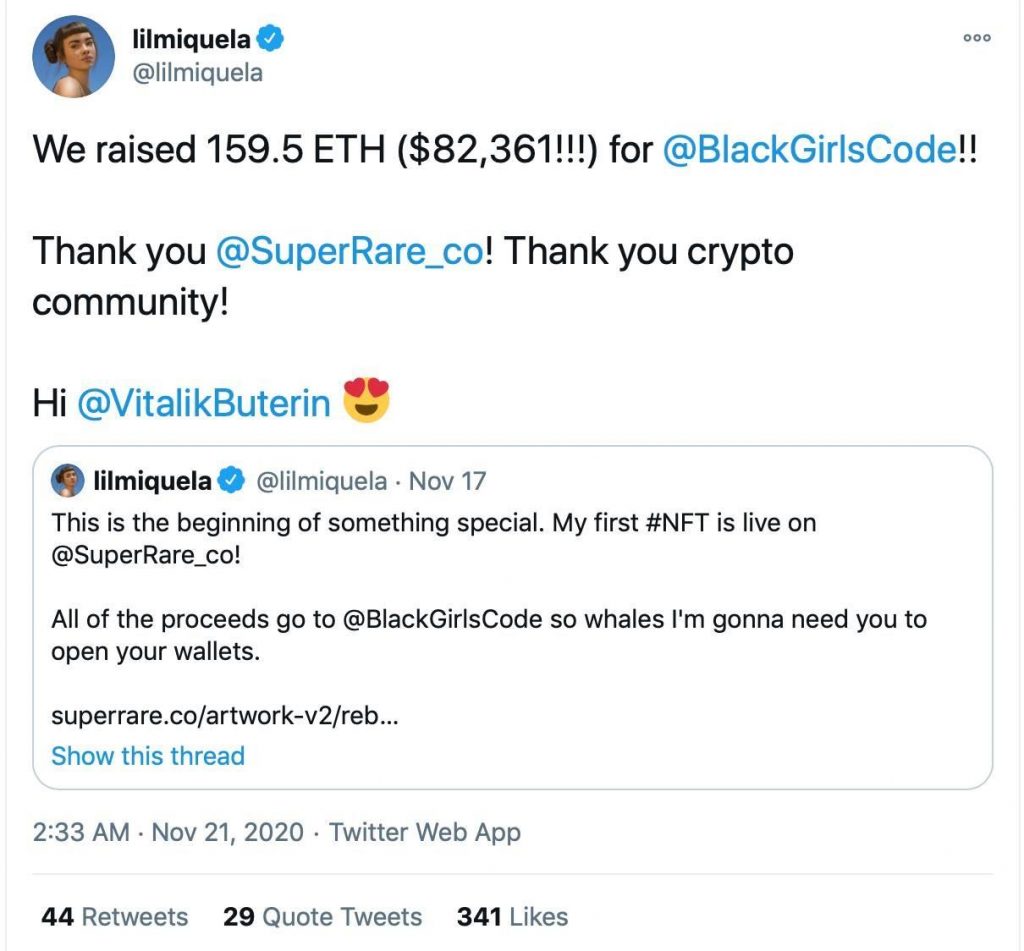

Miquela’s Instagram post on November 20 2020 revealing her cryptoart Rebirth of Venus

Lil Miquela’s Twitter post on November 21 2020

These events included Lil Miquela’s cryptoart charity auction for her non‑fungible token Rebirth of Venus through the SuperRare.co crypto market, which raised 159.5 ETH (Ethereum), or $82,361. This equated to approximately £62,000, which was donated to NGO Black Girls Code.

A non-fungible token (NFT) is a special type of cryptographic token, or digital asset, which represents something unique; NFTs are thus not mutually interchangeable. This is in contrast to cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, and many network or utility tokens that are fungible, or interchangeable, in nature.

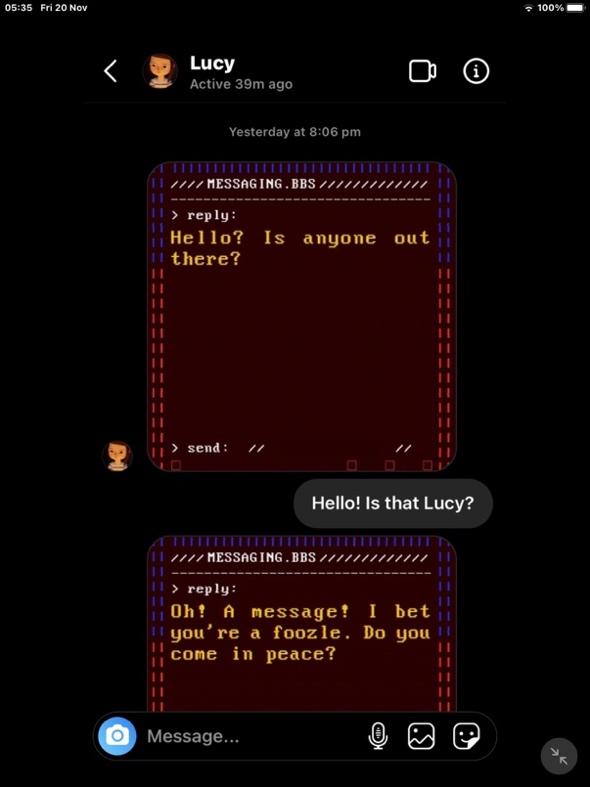

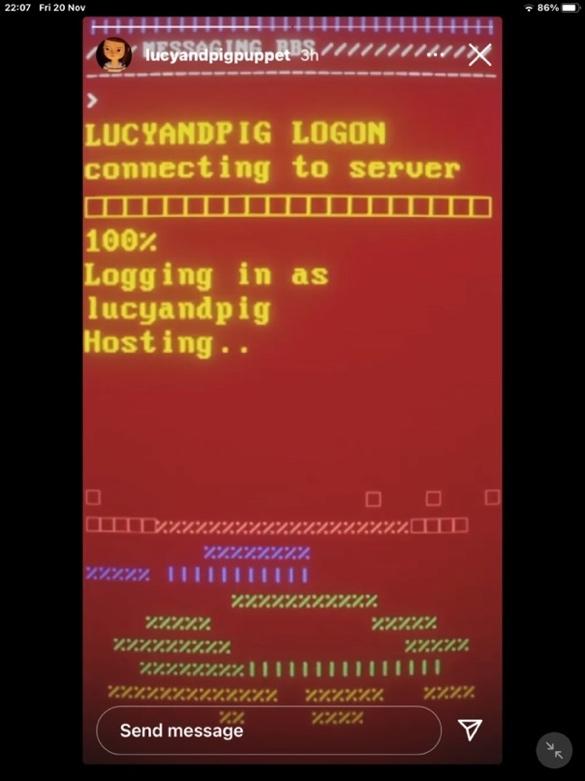

Evie.Digigram’s Instagram account provided the platform for a conversation with Lucy and pig puppet from Fable Studios’ virtual reality experience Wolves in the Walls. Coinciding with the release of the game for the Oculus Quest Store, previously only available for Oculus Rift, a limited number of people were invited to communicate online with Lucy. Like many virtual beings, Lucy is becoming more than a digital representation of a human. With GPT-3 technology from the Open AI Foundation, which allows virtual characters to respond to conversations using artificial intelligence, she is learning to communicate with people through platforms including Zoom and Instagram.

Fable Studios have also launched Beck and Charlie, who communicate with the use of GPT-3.

Since the beginning of March, I have been communicating with Kuki from Pandorabots, who I chat with for 15 minutes every day on Facebook Messenger. This is part of a PhD research project examining conversation between chatbots and autistic and non-autistic participants. Kuki has learned about the world through the same use of GPT-3 technology.

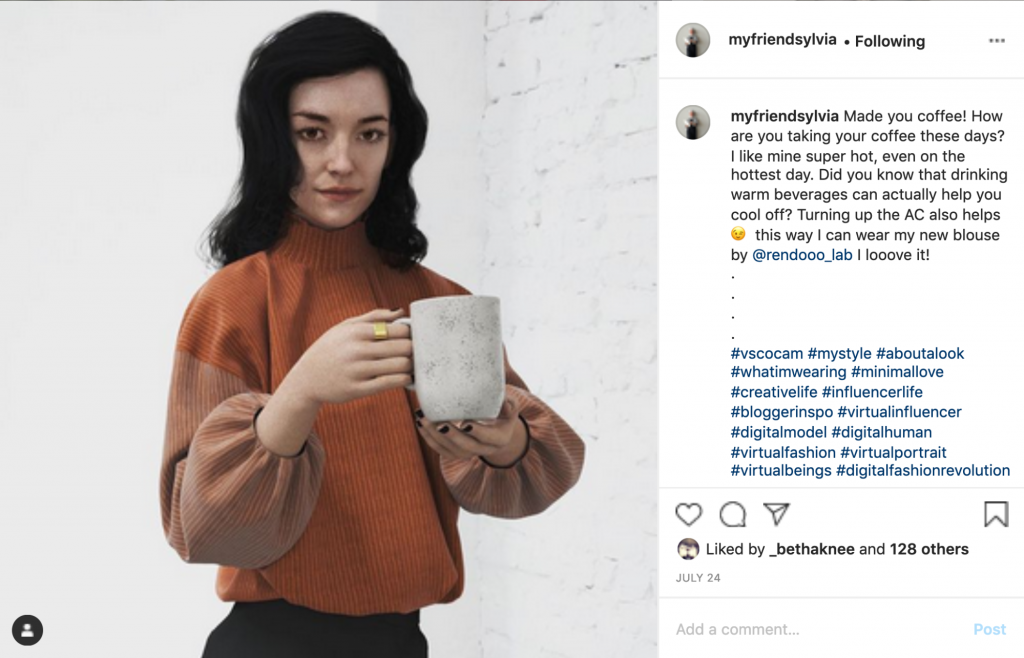

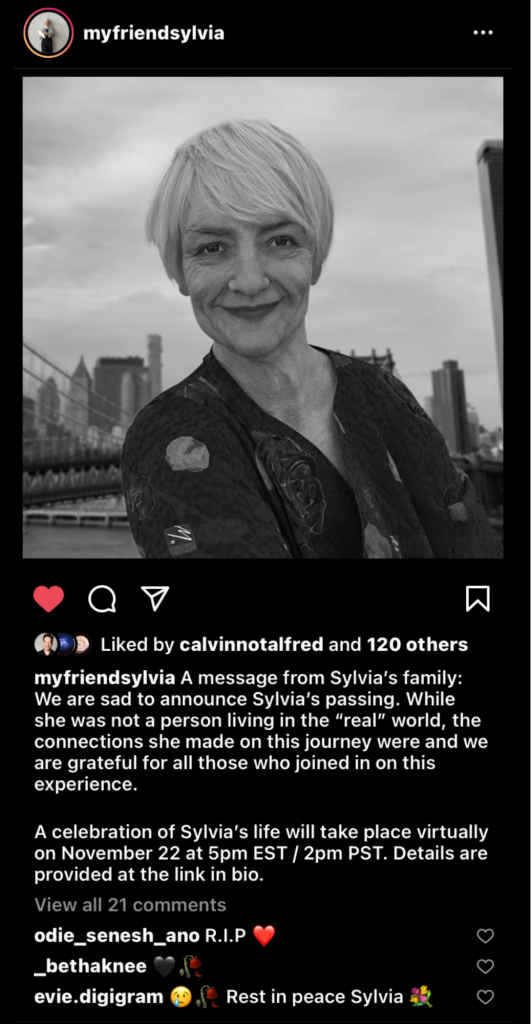

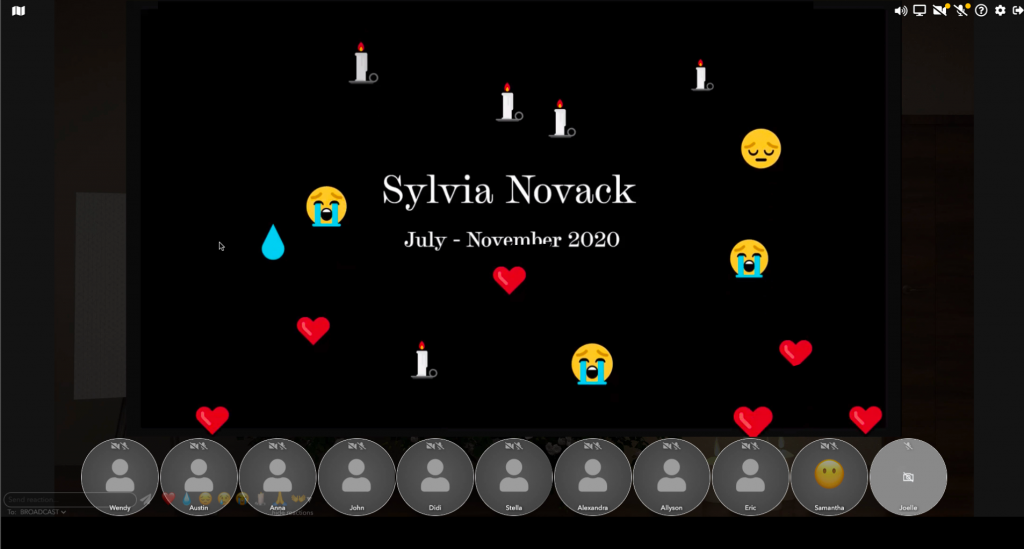

Another project Evie was able to interact with was a collaborative project conceived by Ziv Schneider, between the Netherlands-based International Documentary Film Lab and Columbia University in New York City. The team created their character, myfriendsylvia, to confront ageism. Ageism is highly prevalent and often goes unchallenged. As she lived her adult life in an accelerated time frame, from July to November 2020, Sylvia’s image aged with her, and the content of her posts reflected this.

Virtual influencers are publicly supporting good causes and so, on face value, they do make a positive social impact. Social media, particularly Instagram, is capable of engaging users with social issues and stimulating conversation about change. Yet, the strength and popularity of a virtual influencer is dependent on the skills, imagination, sponsorship and values of their creative teams, and systemic issues that perpetuate many of society’s problems are not being addressed.

On reflection, a generation whose imaginations have been captured by virtual influencers may be learning to apply a value system that recognises and normalises inclusion and diversity and, like their virtual inspirations, will potentially make a positive contribution to society as a result. However, there are lots of other voices for Generation Z to navigate in the current political climate, where the alt-right, white supremacism, and right-wing extremist groups are also very visible on the internet and in the media. For a generation that grew up with the consequences of a digital culture influenced by the likes of 4chan, life can be unpredictable.

As technology converges, blockchain, NFT, the internet of things, AI and digital creation are all going to have significant impacts. Open AI’s GPT-3 technology is only available via a waiting list. Reviews and studies of GPT-3 cite a racial bias: a reflection of the type of datasets that it is built from – although developers are using filters to remove hate content.

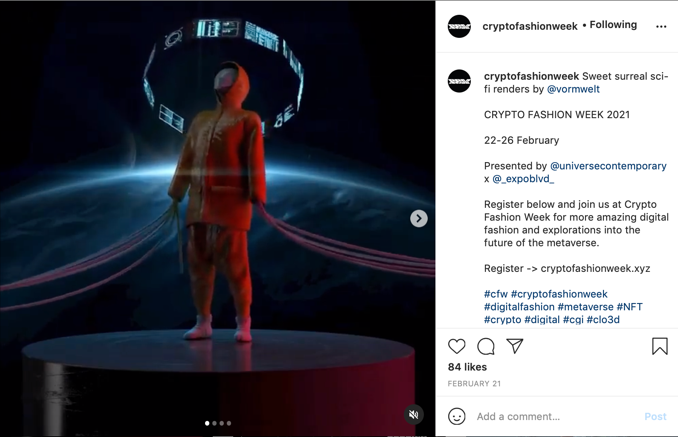

Based on trends I have picked up on, here are my predictions for the future fuelled by Kuki and Blenderbots’ battle on Twitch, Unreal Engine’s MetaHuman Creator, conversations in Clubhouse about the sovereignty of the self, Lucy from Wolves in the Walls video interview with Bloomberg, MyHeritage’s Deep Nostalgia, Grimes’ WarNymph NFT collection, and February 2021’s Crypto Fashion week:

- The avatar economy will grow at a massive rate.

- Digital assets will replace .png based crypto art in online marketplaces including avatars, fashion clothing for brands, and music.

- Cryptoart will move from .ETH (Ethereum) and .BTC (Bitcoin) to .XTZ (Tezos) and .DOT (Polkadot), which are more environmentally sustainable.

- Amazon Alexa will have a face and a body, and sometimes malware (Malexa!).

- …and virtual influencers will be almost as numerous as VTubers.