Listen to Dawn’s accompanying podcast exploring coral soundscapes here.

Soundscape Ecology

From the growl of a grizzly bear to the melody of a songbird, every environmental niche has a soundscape. The soundscape is the chorus of noise in a habitat and researchers are listening to these natural symphonies to reveal previously untapped potential in ecosystem conservation.

In Ecuador’s tropical forests, scientists at the University of Wurzburg have recently used bird calls as a marker of soundscape health. Between hummingbirds and harpy eagles, an abundance of bird call indicates the many functions at work in a thriving forest.

“There are species with long or short beaks that eat seeds and fruits from various areas of the forest ecosystem. Therefore, the idea was that these bird communities would give insight to the ecosystem health as a whole,” says Jörg Müller, conservation ecologist and lead author of the study.

Müller and his team found that mapping bird calls provided a better picture of an ecosystem’s health than simply monitoring the number of birds in the area.

Experts native to Ecuador identified each species by sound, and from this data, a neural network model was created with the ability to pick out 75 different bird calls. Each bird’s species pitch and tone was measured by an acoustic index analysis.

The conclusion: bird call composition was an accurate measure of recovery in the forest – each unique call was part of a dynamic picture of the ecosystem and its health, measured as a sonic landscape.

The researchers were also able to create a forest disturbance gradient from the bird call cues, since tree composition is mirrored by the makeup of its bird diversity. In ecosystem conservation, it’s often difficult to identify which forests are recovering from disturbance or are old growth. Recovery forests are old growth forests that were damaged and are in the process of renewal.

“If you are on the ground in this thick forest, you cannot see [the recovery], but you can hear their bird cries. When I looked at the bird composition, we could see the answer clearly,” Müller says, suggesting the interpretation of soundscapes as a useful tool for understanding a forest’s disturbance level.

Other Uses of Soundcape Research

Soundscape research has other uses, too, according to Whitney Wyche, a researcher for the National Park Service, who monitors the soundscape at the mountainous Glacier National Park in Montana. She recently compared contemporary soundscapes to previously collected data from 2004 as a way to quantify the effects of noise pollution over time.

The audible chorus of sounds in the park comes from its distinct wildlife such as elk, bighorn sheep, and bears. However, many audio signals might not be so obvious.

“To understand the entire soundscape, you need the whole picture,” Wyche explained recently at the Geological Society of America’s annual conference.

So what does it take to measure the sounds of flora and fauna in their entirety? The answer lies again in a combination of complex acoustic equipment and artificial intelligence. Wyche uses a sound level metre to record audio signals, while also recording background audio to programmatically identify non-obvious and non-natural sound sources. Take a listen to a bear taking a bite out of Wyche’s microphone.

Glacier National Park, Montana, USA

The low hum of an aircraft, the noise from passing cars, the music of a Bluetooth speaker are all examples of unwanted intrusion that can affect both visitors and wildlife in natural areas. Focused efforts can help mitigate this; a recent plan implemented in 2022 reduced noise pollution from aircraft over the park.

“In 2004, there were more low-flying aircraft for visitors to sightsee in the park, and now there are fewer routes due to the air tour management plans, which means less propeller noise pollution.” Wyche says.

Writing further, in an internship blog, Wyche elaborates on the direct impact of sound. “A predator that can hear sounds within a radius of 9m² in a natural soundscape would only be able to hear sounds within a radius of 7m² if one decibel of sound was added to the natural soundscape.”

The Natural Rhythm

There is a growing body of evidence that shows noise pollution interrupts the natural rhythm of the environment – disrupting animal calls, mating practices, and hunting. But the soundscape can recover from high human interference, other research indicates.

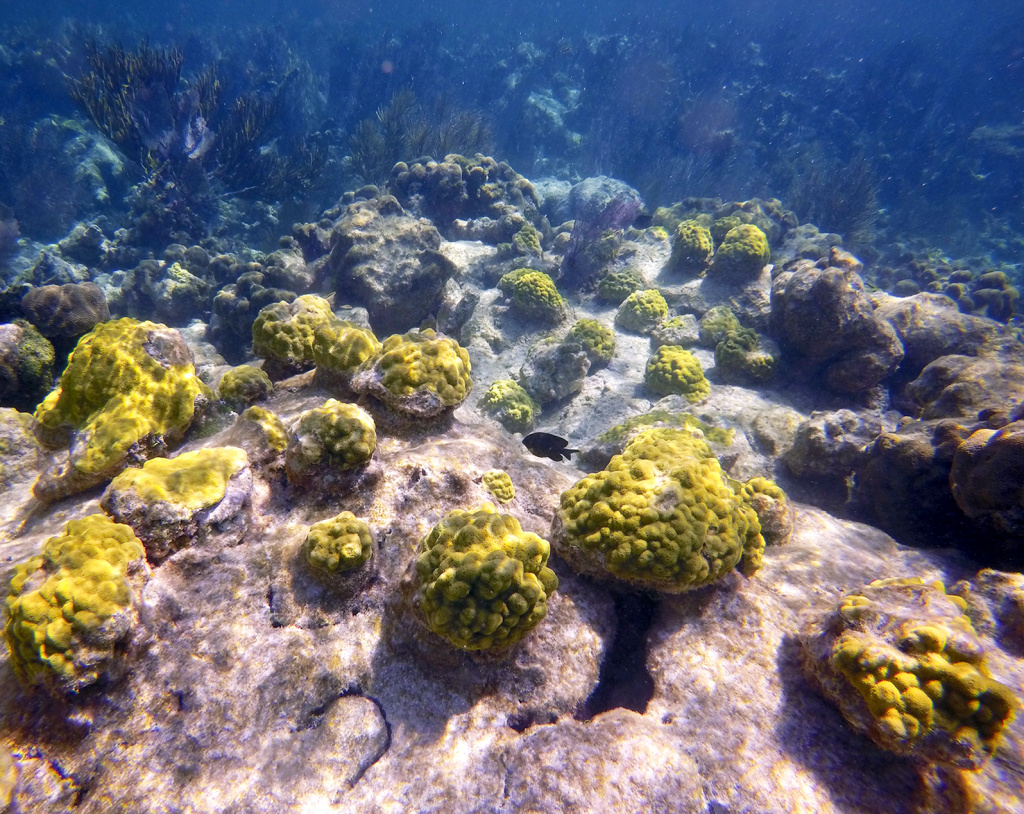

In Indonesian waters, for instance, local fishermen using dynamite in a coral reef to explode and kill fish had also destroyed the soundscape. Researchers from the University of Exeter in the UK compared this highly damaged reef withhealthy reefs and found that restoring the reef healed the soundscape and its audible array of species. The team installed reef stars at the site; metallic structures that attach the fragmented reef back together, helping to stabilise it.

Restored coral in Florida Keys, USA

“We watched the reef grow back and the soundscape come back,” says Lucille Chapuis, an author of the study. When the researchers listened to the recordings, they found 10 distinct fish sounds occurred at least 50% more in healthy and restored reefs, than in degraded reefs.

This has a feedback effect as baby fish choose the loudest, most bustling reef to call home and settle down, thus prolonging the restoration effort.

Soundscape research is key to protecting our planet, and alongside its power as a conservation tool, there is also wonder in monitoring these sounds