I met Frederick Douglass face to face. In 2021.

His head held high, Douglass appeared dignified as always. His eyes darted deliberately, scanning his surroundings. He tried to hide his displeasure, as you might pretend to appreciate a thoughtless birthday gift. But an increasing cloud of melancholy moved across his face; his brow furrowed ever-so-slightly, his mouth twitched, and you could sense his frustration.

Then, he noticed me. And for but a second, his eyes softened and the corners of his mouth curled with pride. He looked genuinely happy to see me. Before my own eyes could properly swell with tears, Douglass bowed his head, the smile faded, and his steely eyes fixated on me, delivering not only an urgent message but a grave responsibility: “There’s still work to do”.

As a Black person but especially as a Black writer, I have always admired Frederick Douglass. Douglass lived during America’s antebellum period, during which it was illegal to teach enslaved persons to read. Douglass achieved literacy anyway, slyly goading white laborers into telling him what various words spelled out by insinuating that they themselves could not read. After escaping slavery, he became known as a renowned writer and orator, sternly advocating for abolition. If Frederick Douglass believes there’s still work to be done, I know I had better get to it.

That video clip of Douglass, created by Dr Joanna Davis-McElligat, Professor of Black Literary and Cultural Studies at University of North Texas in the US, was my introduction to ‘deepfakes’: text, audio, or video created using artificial intelligence and an algorithmic computer-training method known as deep learning. Deepfakes make a person appear to exhibit speech and movement they didn’t conduct organically. As Dr Davis-McElligatt puts it: “These animated photographs are deeply upsetting and profoundly moving at the same time.”

In the wrong hands, deepfake technology poses a grave threat. Think actual ‘fake news’, falsified history, identity theft, and even non-consensual AI pornography. Yet, despite its dangerous potential, this synthetic media does have some upsides. For myself, in particular, deepfakes gave me the opportunity to forge a connection with my late relatives and ancestors in a way which was previously impossible.

The Atlantic Triangular Trade and the resulting displacement of African peoples created a traumatic void in which Black people lost much of our language, culture, traditions and, perhaps most catastrophically, our genealogical history. Birth names were stripped away and replaced; blood relatives were forcibly separated; records lost or never filed. Even after slavery was abolished in the US in 1865, the obfuscation of Black people’s family trees never really ended. All manner of physical and systemic boundaries have been put in place to make it difficult for us to find out where, and who, we really came from. With the exception of very few, our ancestors are painted as indistinct apparitions amongst the millions who were enslaved across the globe. Deepfakes confront that theory by restoring individuality, and by proxy, humanness, to static images. The twitch of a lip or the squint on an eye can tell an entire story.

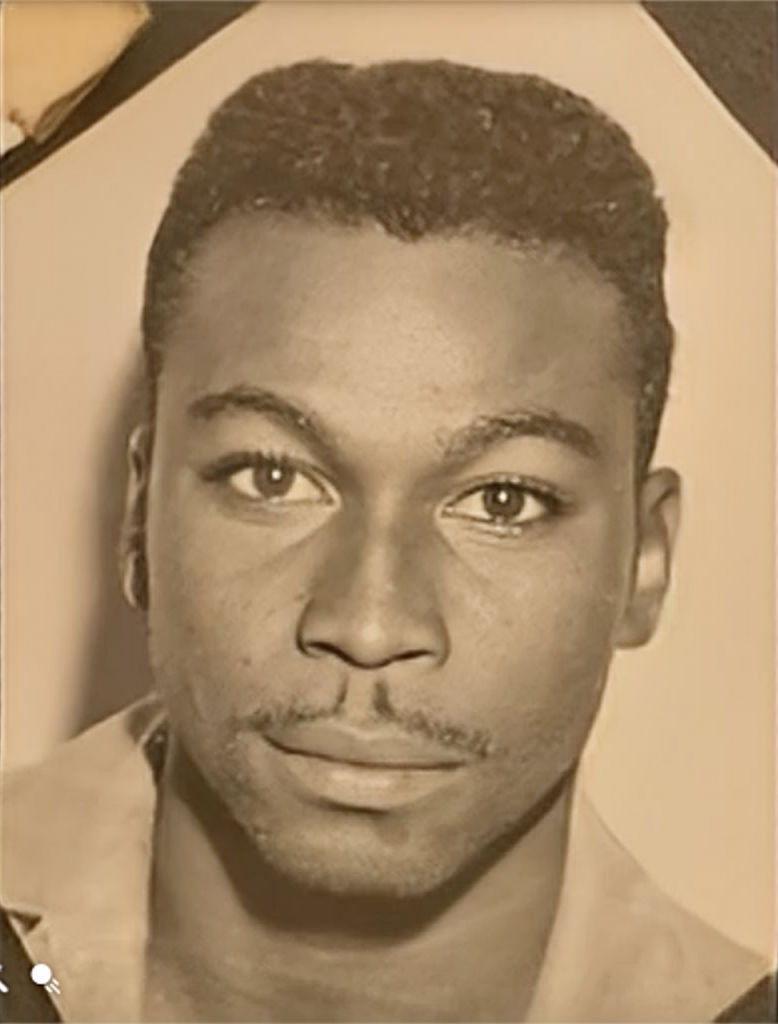

My oldest known maternal relative is my great-great-grandfather, Willie. He is a mystery; I am aware of his existence solely due to a painting of him in my grandmother’s living room. Beyond that, I know nothing about him, his interests or his life experiences. Using the MyHeritage website to create my own deepfake videos, I applied the same movement pattern that Frederick Douglass exemplified in his deepfake video. Despite the two men displaying identical mannerisms, each possesses his own distinct personality. Willie looks more curious; a bit more optimistic.

NOT I, AMERICA

after great-great-granddaddy Willie, with a nod to Langston Hughes

This familiar century. We still

between rock and a rockier place,

they just keep throwing the rock.

I was born well

after Emancipation, witnessed

not slavery but the snake of itself,

splitting its own skin so it could be

called another name.

What you say is a viral video

used to go by public lynching.

Before that, dog sport – blood

hounds clamping their canines,

snouts rubbed raw in your scent.

So to say things have changed

just means you own a thesaurus.

They don’t teach you in school

I was twenty years old before

segregation was legal in my town.

The uphill battle in their history

books is actually a moon

struck tidal wave, its pounce

only bested by its sure retreat.

I too, am not America. I am

better. I taught you better

than that, too.

Writing a poem, to me, is akin to building a relationship. I spend a lot of time with a single poem and the process involves intense thought, contemplation, and a fluctuation of emotions. In one moment I may write twelve lines and then for the next two hours I might scrutinise the placement of a single word. However, as I spend time with the poem, I come to understand it on its own terms: what it wants to say to me, how it wants me to approach. I write in several genres, and poetry is by far the most intimate. There would be no better way to get to know my ancestors than spending time with them in poetry.

The MyHeritage deepfake program gives the option to select from several movement patterns, allowing you to witness different emotions and mannerisms. But no matter which I chose, my deepfake maternal great-grandfather Sam avoided eye contact.

GENERATIONAL WEALTH

after great-granddaddy Sam

Don’t get all caught up on acreage and ass.

Instead, put aside a dime from every dollar

and store spare change in canning jars. Pocket

licked-clean watermelon seeds in ready soil,

don’t waste water when rain will do.

Children don’t comprehend sacrifice, only

embarrassment. Frozen milk, threadbare socks

wounds duct-taped over like helpless hostages,

dresses and dress pants fashioned from grain sacks,

lunch pails rattling with cans of Spam and oyster

crackers. They will resent you only until

they learn to despise inflation just as much.

They assume you wear the same wind-flapped

underwear for three decades, stick clothespins

through exhausted elastic as a symbol of pride

and not of poverty.

Purse your lips. Remind them they won’t die

from day-old bread. What will wreck them:

unscrewing the lids of each Ball jar to find

thousands in nickels, quarters, and your reddest

wishes, unasked, to make way for all their wants.

Regardless of how you use deepfake technology, your ethical boundaries become uncomfortably opaque. Where you choose to draw the line between truth – which is already a hotly-contested concept – and creative license may never be clearer.

More than occasionally, I was concerned that this relationship, manifested in the span of fifteen seconds, was superficial; perhaps even inauthentic. This then opened several cans of worms: are the expressions in these moving images true to character? Yet, as humans experience a vast range of emotions, isn’t it dehumanising to suggest these images aren’t realistic? Should I have done more research? Then again, how much would I really find? Am I denying privilege if I don’t ask my living family members about their memories with these relatives? Or would I diminish the power of the picture, which itself should be a thousand words?

But, having no other opportunity to connect with my ancestors, I was willing to risk potential scrutiny of my artistic process, my morals. Using simulated body language as an anchor, I leaned into imagination. My feelings took priority. I sought to articulate what felt true even if it wasn’t factual, for I had no way of knowing. If inventing lives and personalities for my ancestors is a moral failing on my part, it pales in comparison to the global immorality that left me without a distinct lineage to trace.

Of all my deepfake relatives, I knew the most about my grandmother’s ex-husband, Walter (which, to be clear, still isn’t much). However, this also meant that his reputation was the most contested. My mother has one opinion of her father; nearly twenty years younger, her half-sister has an entirely different perspective. Ironically, when I had only vicarious memories of Walter, his reputation was static in my mind (I sided with my mother, of course). But deepfake Walter is far more complex. Now, we have our own relationship.

Watching Walter as he tries to find the perfect angle at which to admire himself, I realise that my younger self had been denied the benefit of being lied to. For almost my entire life, I knew Walter as a man who had harmed several of the women in his life. But now I can see, as my grandfather, there are certain aspects of himself he would have concealed from me, and other qualities he may have exaggerated. I would not know him as his daughters knew him, and certainly not as his wife. Our relationship would have been more graceful, for I would have been spared his mistakes. It would have been years before I could have seen him in his fullness, as I do now.

“GET MY GOOD SIDE”

after granddaddy Walter

A child’s first image of God

is her father’s face. Not every God

is good, nor great.

Every little blessing

was an accident. You can’t see

God’s face and live.

His backside to you,

His mighty right hand

chucked the deuce.

Would you axe your own

son for a man who wouldn’t

make up his mind?

Every one of your prayers,

ignored, is some fool’s

eager tribulation.

Why would you pray

to a God of sick humor

and sabotaged plans?

Many apocalypses and Xmases

and later, still no return.

God is surely dead by now.

What strikes you

as blasphemy, let me

remind you is my true faith.

In absence of evidence,

I choose to believe the clouds

split open like lips

in the sky, I see the smile of God

or grandfather, gray-rimmed

eyes soft with regret.

I see God. I see a father’s face.

He was a child once.

God is a God of mistakes.

I admit, I often forego fact in favor of the truth. For all I know, Willie would have chastised me for comparing contemporary oppressions to centuries-ago atrocities; Sam may not have been such a spendthrift. But I sought to write poems that explained the origins of my own proclivities. I needed to know that I came from something, a genealogical line that contributed to the person I am today. I needed to see, with my own eyes, that I have a legacy beyond that of mass-produced trauma. Deepfakes provided that affirmation. I found solace in those subtle expressions on my ancestors’ faces, whether any of it was real or not.