In 2016 I was arrested in Gaziantep in southern Turkey whilst filming a documentary. Previously I had only associated the town with ice-cream, its celebrated delicacy, flavoured with pistachios which rain down in the surrounding hills. But proximity to the Syrian border and a suicide bombing at a police station that summer had everyone on edge.

Filming in the street, I was accused of terrorism and espionage, and detained. With the help of an excellent lawyer who worked on my behalf as I spent three days palpitating in jail, I was allowed to leave the country to be tried in absentia several months later.

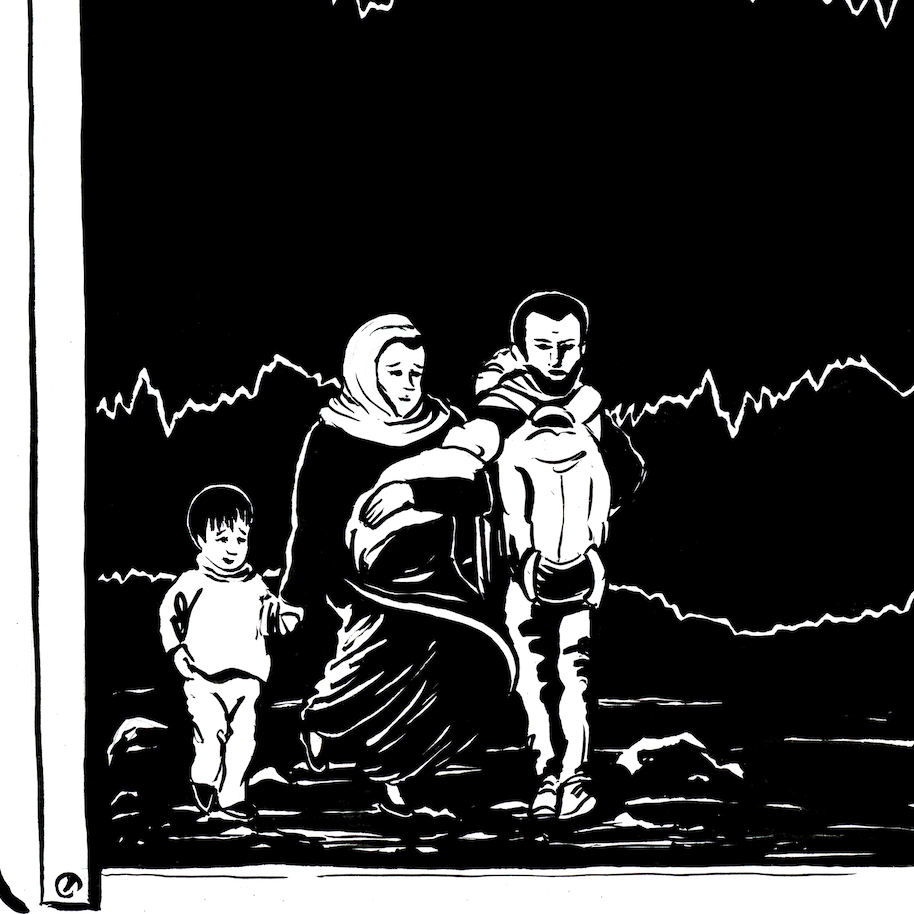

Illustrations by Mereida Fajardo

Despite being quickly cleared by the courts I found myself blocked from international travel. I was repeatedly refused visas for entry into the US and Canada with no reasons attached. And a number of strange things started to happen. People I hadn’t seen for years got in touch to tell me they’d been stopped at internal US airport security checkpoints and asked about me. At borders I was asked about being in places that I’d never visited: why were you in Tripoli during the uprising?

On one occasion, security personnel boarded a plane I had taken from Jordan to Heathrow after filming for a charity in a refugee camp. They prevented anyone else from disembarking in order to escort me to a blacked-out cubicle on the runway. There, they asked what I had just been doing in Istanbul. I replied, gesturing towards the plane: “That’s Royal Jordanian. It just landed from Amman.”

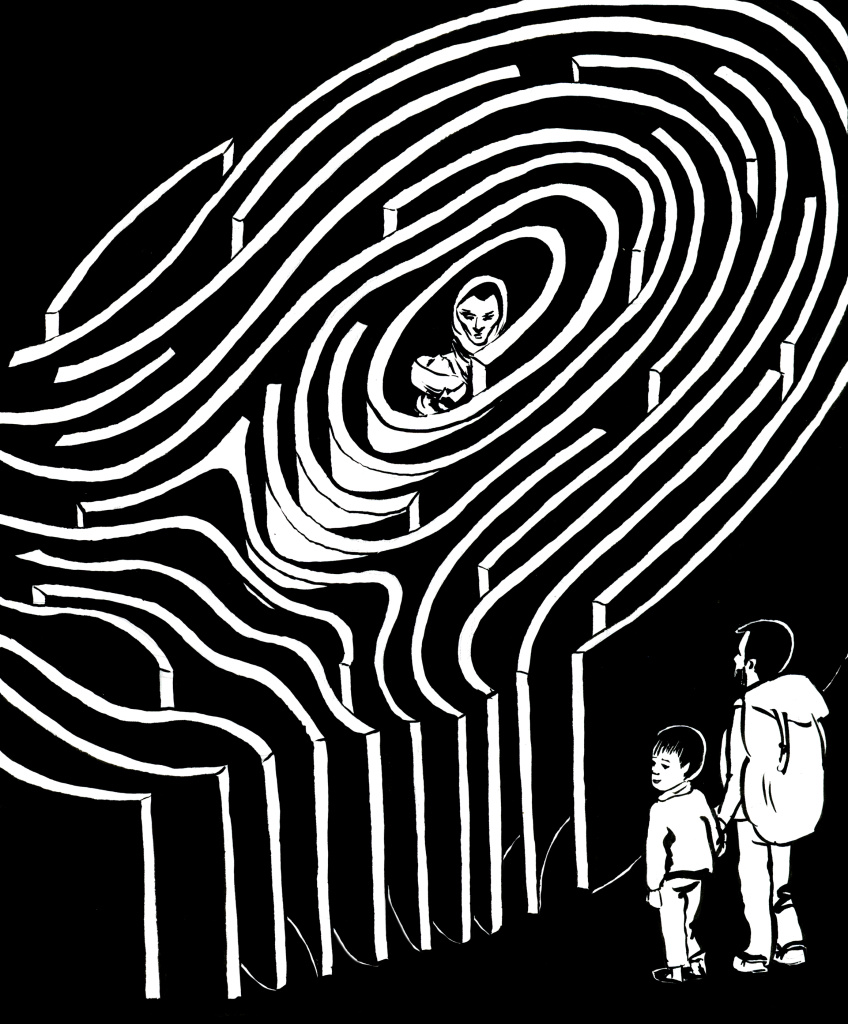

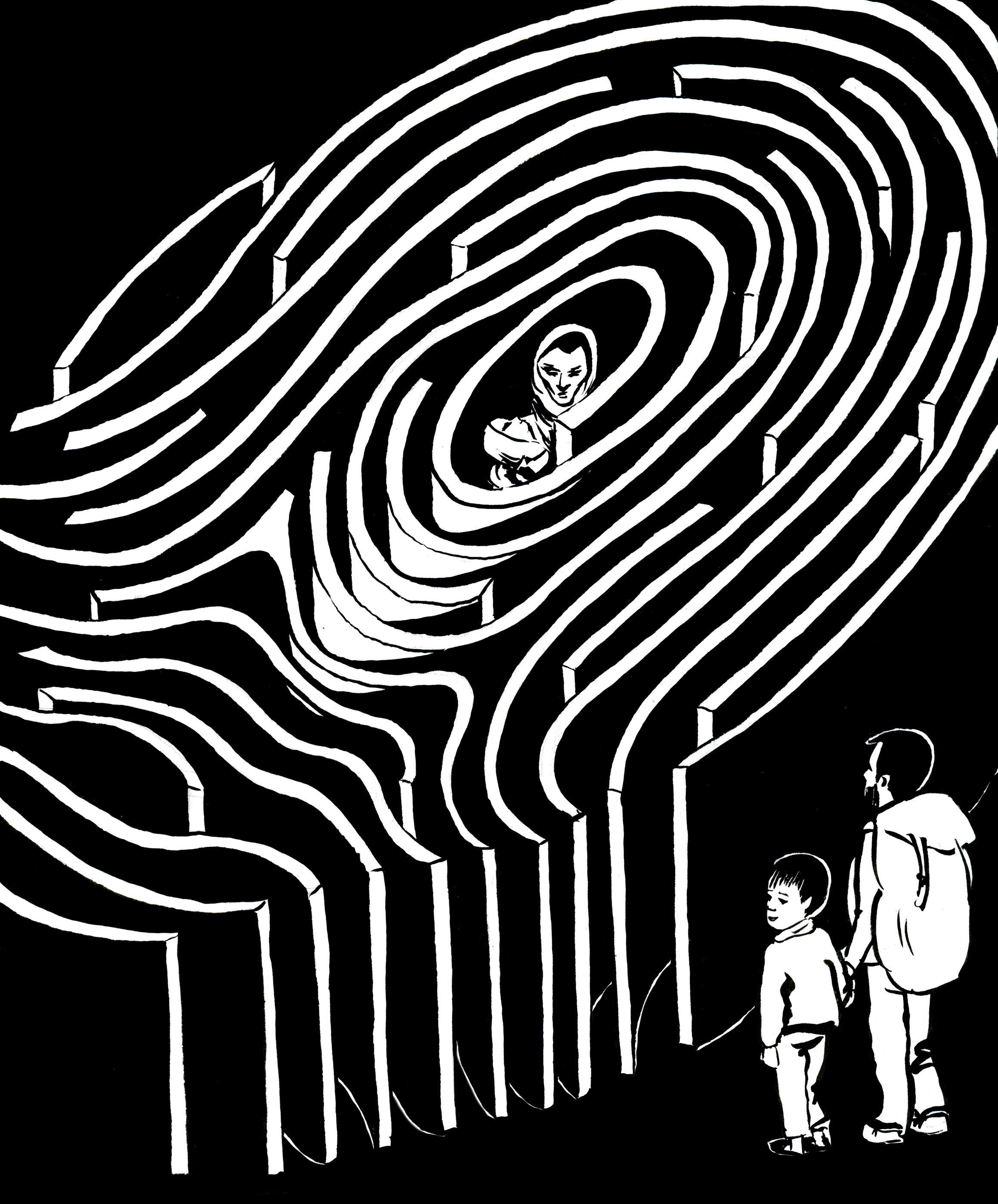

It seemed impossible to get to the bottom of what was going on. A friend who had worked in a government security service advised I likely had my name on a ‘greylist’ – a database that no one can access but from which information can spread. It was going to be impossible to remove me because, to all intents and purposes, the list doesn’t exist.

The warning that had been attached to my name had become detached from the truth, the source, the reason. No one using the database could see where that answer had come from – just that the answer was ‘no’.

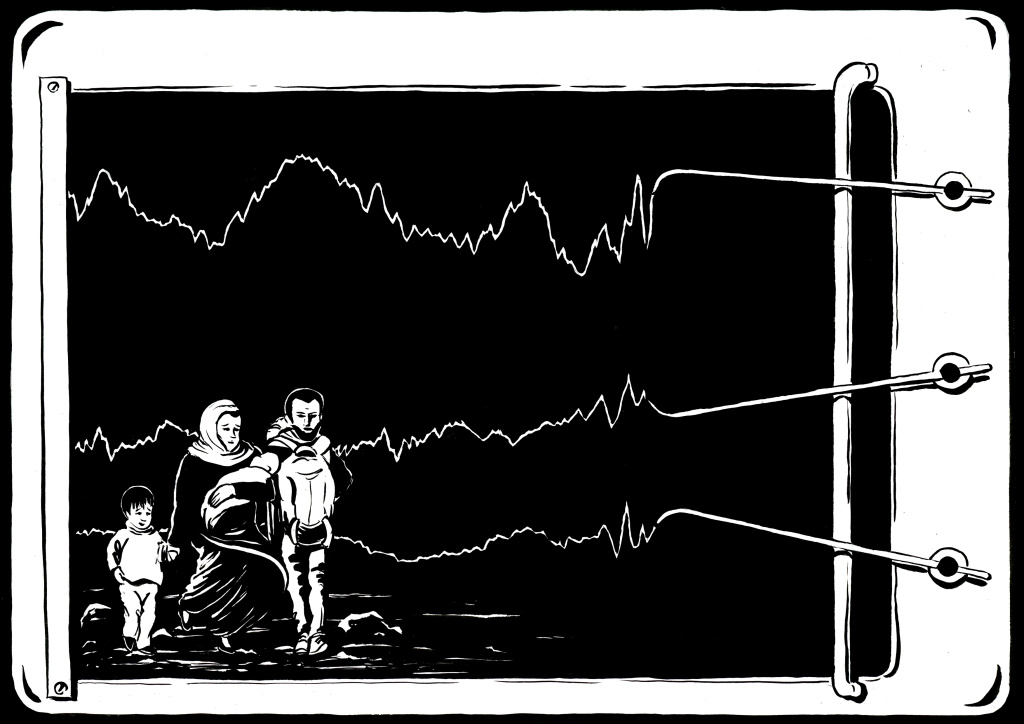

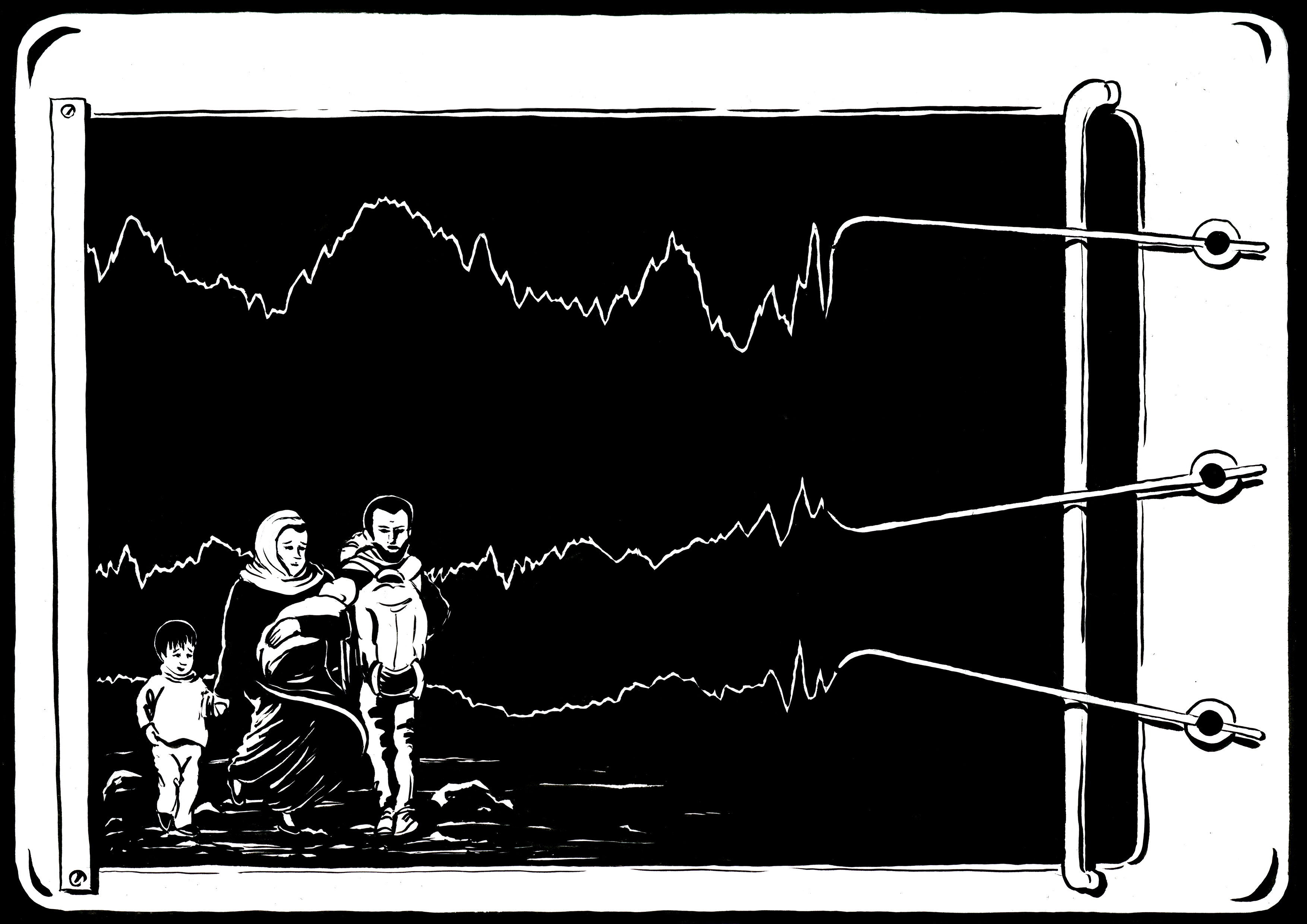

The greylist is just one example of what happens when we let technology into our border systems. The ‘smarter’ or more automated these technologies become, the more we unwittingly create a system with invisible, irreversible consequences; especially for vulnerable groups like asylum seekers for whom crossing borders is an inalienable right.

The rise of border technology

It’s 1948 and the UN is a young and hopeful body, recently established in the wake of the most brutal war in living memory. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights enshrines the legal freedoms of people to move away from places of persecution; three years later, Britain leads the drafting of the more detailed UN Convention of Refugees, to lay out the rights of refugees and responsibilities of host states. Once an individual touches British soil to seek asylum, they must be given due process.

Among the British public at the time, while there was growing awareness of the consequences of being trapped in conflict zones and democracy activists were being celebrated, anti-immigtration sentiment was also increasing. As the empire shrank, many non-white subjects were making their way to their imperial rulers’ home, where, legally, they were citizens. Soon Enoch Powell would speak of ‘rivers of blood’ and immigration would be established as the divisive topic it remains: a country that has invaded most of the globe bewailing being ‘invaded’ by its own people.

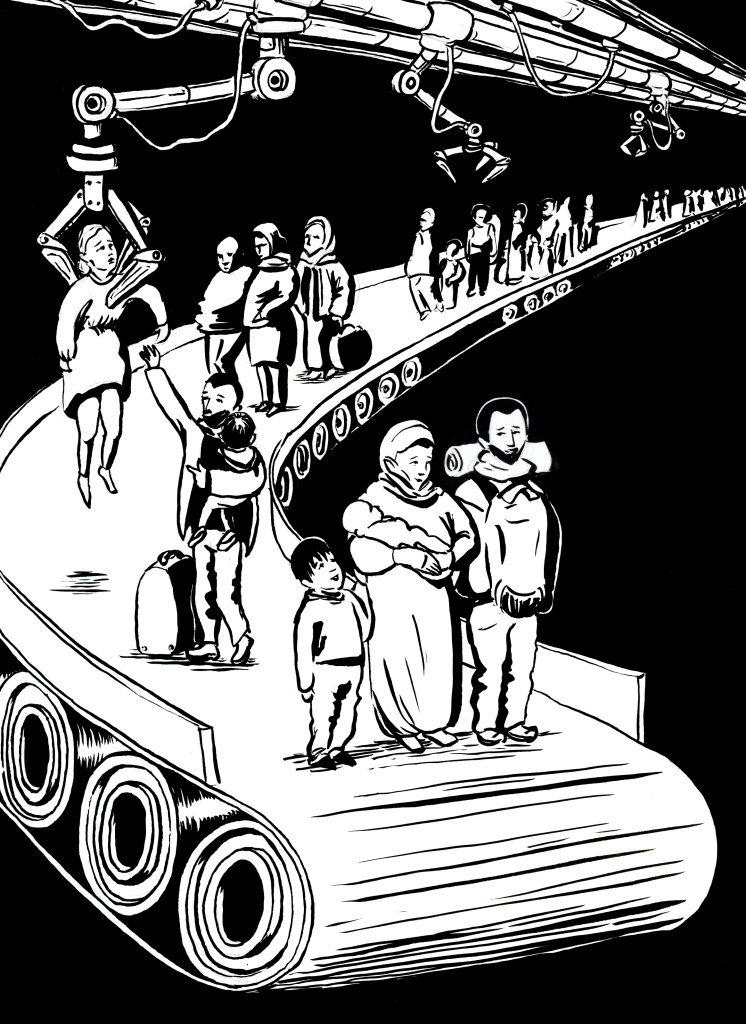

By 1985 The Times was describing the arrival of under 1,000 people fleeing civil war in Sri Lanka – a former British colony – as a ‘flood’, and declaring: “Disturbances in Sri Lanka are a pretext for evasion of immigration control.” Soon after, an act of parliament passed meaning carriers – train companies, airlines – could be fined £1,000 if they transported anyone without documents to the UK. This law shifted everything. The onus of refusal was now on the transport business at the point of departure: not on the government at the point of arrival. In the five years that the law existed, the government collected over £30 million in fines.

A country that has invaded most of the globe now bewails being ‘invaded’ by its own people.

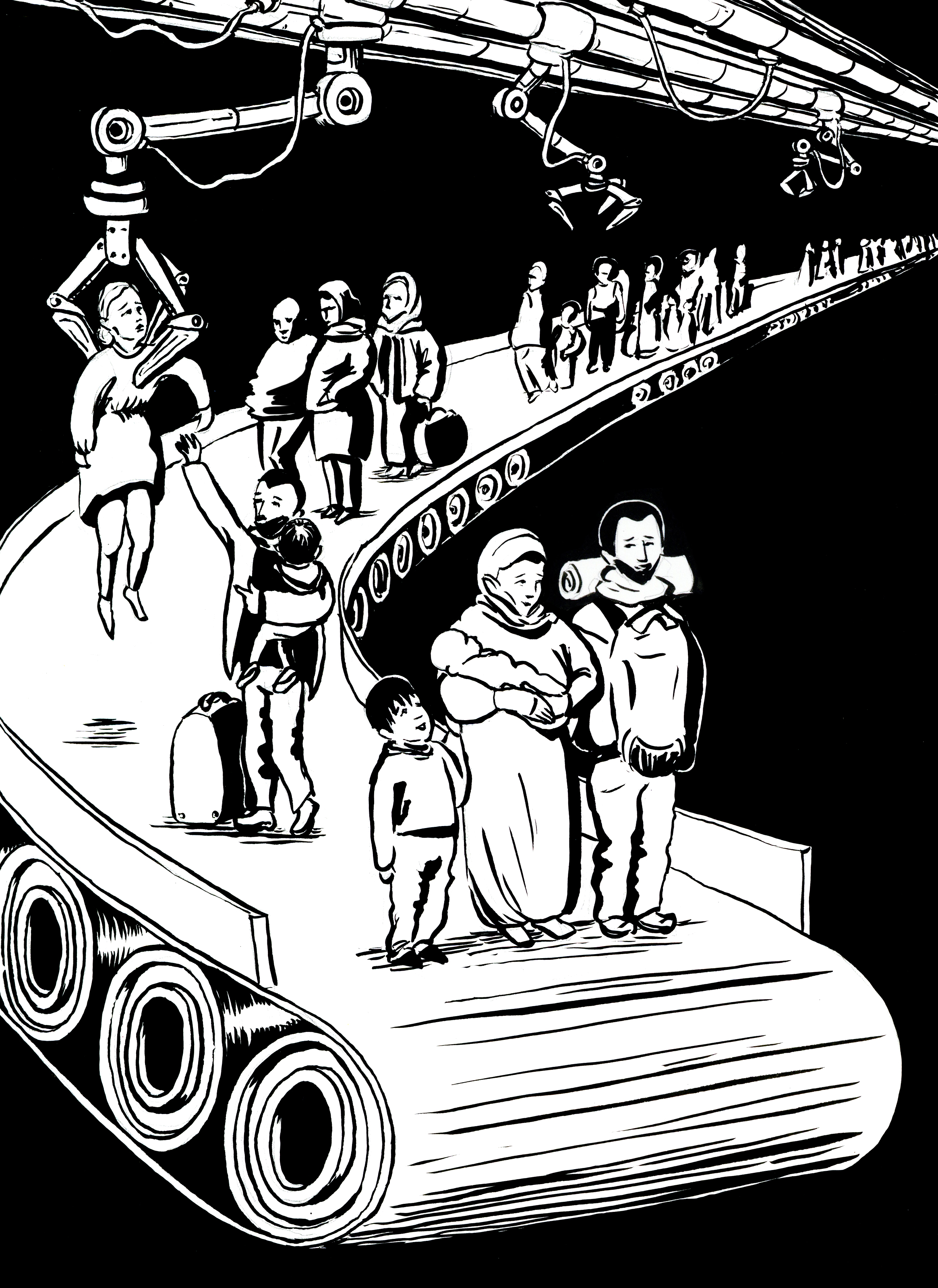

There was outcry among legal advocates and the UN, who rejected bureaucracy standing in the way of life. Increasingly, people turned to more dangerous routes. In 2000 the UK made it a crime to assist someone to illegally cross a border, regardless of their refugee status. The UK government also criminalised migrants themselves: presenting false documents could lead to prison. The boats that cross into Europe are symbols of desperation and risk (during the first half of 2021, deaths at sea doubled) – but this erases the complicity of UK law in forcing this situation, and ensuring the smugglers are cast as villains for extracting cash from vulnerable individuals.

When this game of cat-and-mouse between asylum seekers and UK borders combines with new surveillance technology, the consequences are huge – but difficult to monitor. “The threat of terrorism, transnational crime or human smuggling are often used as the justification for the growing panopticon of migration management technologies,” says Petra Molnar, Associate Director of the Refugee Law Lab at York University in Toronto, Canada, and a lawyer specialising in migration and technology. “These assertions bear little relationship to the reality on the ground.

“In my work, I meet people seeking safety from persecution, war, and violence every day – people who are exercising their internationally-protected right to asylum. Yet increasingly, they are met with hardline border technologies which make this right to seek safety more and more difficult.”

A story of bad data

In 2012 the UK’s E-border programme was set up to establish a global and fully integrated system to pre-screen passengers before travel, using passenger data and biometrics. The UK Border Agency would then use a number of databases to decide whether to authorise or deny travel. It required every travel agency in the world to communicate in real time with the UK Border Agency, allowing anyone to be refused the right to board at the point of departure by a UK-based official. After costing £830 million the project was scrapped, but more ambitious and covert plans would follow.

This global ambition for border automation – controlling the systems and processes of people traveling around the world – is seen as justified. But border politics are a surreptitious form of techno-colonial control. Western aid given to North African countries comes in the form of militarised border services, and demands to introduce biometric controls are written into trade agreements.

Financed with €53 million from the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, French public-private company Civipol set up fingerprint databases for Mali and Senegal in 2016. France owns 40% of Civipol, while arms producers Airbus, Safran and Thales each own more than 10% of its shares. Corporate actors exert great influence on decisions around the governance of the digital border industry. The value is clear: globally, the industry is projected to be worth $68 billion in 2025. It has to be asked whether this can be considered ‘aid’ when its primary function is to advance the European border agenda, and does more for the donor than the recipient.

The UK government’s 2020-2025 border strategy relies heavily on automation and artificial intelligence (AI), with the aim of creating “the most effective border in the world”. The promised system “facilitates the movement of people that benefits the UK, while preventing abuse of the migration system, and safeguarding vulnerable people”. Here the smart border is set up as one that can differentiate between ‘wrong’ and ‘right’ kinds of traveller. But the databases that need to be created to generate this utopia raise some serious concerns.

In a recent report, the UNHCR’s Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, Tendayi Achiume, argues that in deploying emerging tech in immigration enforcement, data is extracted from groups such as refugees “on exploitative terms that strip them of fundamental human agency and dignity”.

By emphasising the security risk of migrants, it makes it easier to justify treatment that sits outside the law. The UK Data Protection Act of 2018 contains an “immigration exemption”, where an entity with the power to process data may circumvent core data access rights if to do otherwise would “prejudice effective immigration control”. This includes the rights to object to and restrict the processing of one’s data, and the right to have one’s personal data deleted. Both police and immigration officers have powers to place bugging devices for surveillance and hack electronic devices.

The precedent for the marriage between vulnerable groups and tech companies is disturbing. In Nazi Germany, vast amounts of data about Jewish communities were strategically collected to facilitate the Holocaust, largely in partnership with a private corporation: IBM.

Recently, the World Food Program was criticised for partnering with data mining company Palantir Technologies in a contract worth $45 million, and sharing 92 million aid recipients’ data. Chinese AI company Cloudwalk, which has been commissioned to conduct biometric registrations of all Zimbabwean citizens as part of a national digital identity program, openly admits extracting and reusing data to improve its facial recognition algorithms, which are sold worldwide.

Bias during the processing of asylum claimants is well documented. A 2010 study looked at how asylum seekers’ behaviour affected judgements by UK immigration judges. Their decisions were based on ‘common sense’ assumptions about how people act when they are lying. Asylum seekers were refused for expressing both too much and too little emotion, and thus being considered either manipulative or unconvincing.

PTSD can also seriously affect the way an individual recounts their story. Not looking directly at people in authority is a cultural norm in many countries; in the UK avoiding eye contact is often seen as a marker of deception.

Frances Webber is Vice-Chair of the Institute of Race Relations, with 25 years’ experience as a practising immigration lawyer. “In a world full of wars, we have an asylum procedure built around officials’ belief that asylum seekers are likely to be opportunistic liars, that the scars they bear are self-inflicted, that suicide bids are blackmail attempts. This is a covert war against asylum. It is resisted every day by refugees and their lawyers – and is a crime against humanity.”

Truth is in the AI of the beholder

Abu is from Senegal but now lives in Bristol, UK. He was searched and questioned in Dublin Airport for five hours while trying to travel to the UK with his two-year-old daughter. She has a British passport; Abu had a valid visa. “I wasn’t an illegal immigrant,” he says. “The border guard stopped me, and searched all my contacts on my phone. They even look inside my daughter’s nappy. I was accused of smuggling cocaine, they said that they found traces of cocaine in my blood. That was a lie. We were left without food. It was a horrible experience.”

Framing immigration control as an exercise in truth validation has spawned an automated lie detection subsection of the border tech industry. Regardless of whether lie detection is even possible (the notion that polygraph tests detect lies is false; a brain scan was used as evidence to convict an Indian woman of the murder of her husband in 2008 but her sentence was later overturned), the implication of lying-until-proven-truthful represents a powerful bias.

Projects such as iBorderCtrl and Avatar (Automated Virtual Agent for Truth Assessments in Real Time), which were trialled in 2020 and 2018 respectively, use a mixture of retinal movements, voice detection, face recognition, emotion recognition, and language analysis to support decision making at borders.

iBorderCtrl uses ‘The Automatic Deception Detection System’, which quantifies the probability of deceit in interviews by analysing interviewees’ non-verbal micro-gestures. There are well-documented issues on the basis of racial bias with these technologies. A report on facial recognition technology deployed in border crossing contexts, such as airports, notes that even though the best algorithms misrecognised Black women 20 times more often than white men, the use of these technologies is increasing globally.

Avatar and iBorderCtrl use AI to learn through feedback to improve results. This ultimately makes it impossible to pinpoint the reasons an answer has been selected. This phenomenon – known as AI Black Box – is highly problematic when putting something as scientifically questionable as lie detection into an unaccountable system.

“The algorithms used to power this technology are vulnerable to the same decision making of concern to humans: discrimination, bias and error,” says Petra Molnar. “Our procedural rights are also impacted including the ability to meaningfully challenge an automated decision, or even know which types of automation we are interacting with when decisions about our migration journeys are being made by state authorities.”

But there is a collective drive to will these technologies into being and continue to hunt for the elixir of the intelligent automated system. Despite the outcome of previous trials, the UK’s December 2020 Border Strategy announced the launch of Seamless Flow – a facial recognition system now trialling at Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport.

Even the names – Seamless Flow, Avatar – and their slick websites, speak to a fantasy of technology as salvation. In this mythical world, technology is always clean and it always flows: it never jars or sticks. Technology is neutral, above human error, and so somehow freed from the discrimination and bias that concepts like ‘migration’ and ‘refugee’ are loaded with. Introducing technology promises to separate governments from the messiness of decisions, under the burden of which immigration systems appear to be breaking.

“The people I speak with talk about feeling dehumanised by increasing data collection, and worried about what biases or discrimination they may encounter on the computer screen,” says Petra Molnar.

“They speak about drones patrolling the waters instead of search and rescue vessels, leading to thousands of people dying during their crossings. Instead of more resources for access to justice, or basic services like education and resettlement, we have massive amounts of money funneled into smart borders, surveillance equipment and automation.

“The turn to techno-solutionism at the border shows a global appetite for using technology as a band-aid solution to complex problems, a lucrative business of ‘big tech’ instead of thinking through the systemic reasons why people are compelled to migrate in the first place.”

Migration is not a crime

In 2018 and 2019, the UK government faced high-profile deportation scandals. Firstly, Home Secretary Amber Rudd made an ‘unprecedented’ apology to people who had settled in the UK as children of the Windrush generation of emigrants from the Caribbean, but who had been denied healthcare, lost their pensions and been threatened with deportation for not having the correct paperwork.

The following year the UK mistakenly deported more than 7,000 foreign students after falsely accusing them of cheating in English language tests. Though this was widely documented, none were given recourse to appeal the decision. The people impacted by these kinds of mistakes have the least power to advocate for their rights: there is presently no regulatory body overseeing border technologies, and while civil rights groups such as AWO and Foxglove do sterling work, they rely on private donations.

These examples go against the government narrative that the system is designed to make sure the best people are let in, while political hysteria around the ‘migrant crisis’ drives an agenda that prioritises keeping numbers of migrants low. The perceived ‘threat environment’ at borders, mitigated with intrusive technologies like drones and surveillance towers, are thus normalised in the minds of the public. It makes us lose connection with those who die on the journey, and offer compassion rather than justice.

The use of military and surveillance technologies also bolsters the imagined connection between immigration and crime. The EU has earmarked €34.9 billion (£30 billion) in funding for border and migration management for 2021-27. Much of that is funnelled to Frontex – a militarised EU border force. It watches migrant movements in the Sahara, Mediterranean and Atlantic using satellite surveillance and deploys land and sea patrols to stop them. Military grade untested drones and devices which can detect heartbeats are used to monitor movements.

Frontex is under investigation by the EU Fraud Watchdog over a range of claims, including allegations that guards had been involved in forcing refugees and migrants out of EU waters at a Greek-Turkish maritime border.

Katarzyna Bylok is a human rights activist and sociologist based in Australia. The country has a refugee policy that Human Rights Watch has branded ‘cruel’, with asylum seekers detained – sometimes for years – in offshore processing centres.

The UK government is considering similar offshore processing as part of the Nationality and Borders Bill, despite the UNHCR (UN Refugee Agency) urging lawmakers to reject “dehumanising” practices. It’s a bill that also, shockingly, means that anyone travelling by ‘illegal’ means to the UK will automatically eschew their right to make any claims on asylum. It criminalises anyone who helps them, even if done without payment, to enter the country.

“Mandatory detention, Home Office ‘hostile environment’ policy and talk about illegal or economic migrants criminalises and dehumanises the asylum seekers, which in turn creates public distrust,” Bylok says. “These policies consciously create artificial distinctions between those who are ‘genuine’ asylum seekers and ‘economic migrants’ – the worthy and the unworthy, the legal or illegal. In fact, no human being is illegal.”

‘The ever-expanding use of surveillance and smart border technology affects all of us’ – Petra Molnar

I was finally able to clear my name from the non-existent greylist. It took a letter from the office of Robert De Niro, who had invited our studio to present an interactive artwork at Tribeca Film Festival in 2019. It felt ludicrous that, after years of being told there was nothing I could do, this was the strategy that worked. But then, perhaps it makes sense that to get your name taken off a non-existent list, you need the endorsement of a man best known for playing a fictitious mafia thug.

I’d only had a very minor taste of what it would feel like to face an inexplicable barrier on the basis of an error. But it brought a sudden awareness of the personal consequences of mishandled data.

What are we ready to accept for others and ourselves? The Covid-19 pandemic has led to a rapid increase of bio-surveillance – the monitoring of an entire population’s health and behaviour, facilitated by emerging digital technologies, is now, suddenly, normal. These experiments on migration populations are not far from becoming the experience of the ordinary citizen. But as their experience remains kept at arm’s length, oversight is impossible.

“The ever-expanding use of surveillance and smart border technology affects all of us, not just refugees crossing borders to seek safety,” Petra Molnar says. “The ability to challenge the opaque and discretionary decisions made about us in technology-supported border and immigration decision making is a fundamental part of a free and democratic society.”