I consider myself as being born and raised by the internet.

Born and raised by hidden IRC chatrooms. By message boards about special interests. By writing to friends late into the night about everything from favorite TV shows to our innermost feelings. This formed my understanding of community, quite literally — writing with those strangers gave me my name, a language I could use to describe myself, and aspirations of what my future could be. I created the persona of myself that I would eventually grow into.

Time spent on message boards dedicated to creating custom MySpace layouts turned into a full time career as a designer in tech, time spent in gay chatrooms turned into forming community spaces alongside successful queer men I could look up to, and a hastily chosen name as an experiment turned into the understanding that I could survive and grow up to be a transgender adult.

In a very real sense, the virtual world led to a becoming that is intrinsically linked to my core sense of self-identity.

Digital Becoming

For me, this form of virtual expression goes back to the early 2000s, the time of MySpace, part of the Web 2.0—the pure customisability of a user’s profile enabled me to create an online presence that I then performed. I created not just in the form of image or video like social media now, but in forms like creating MySpace layouts coded in HTML and CSS to show off my favorite bands.

These communities were places where I could form my personal identity online, disconnected from my ‘real-life’ personal information, through the customizability of the technology. I used it to depict an idealized version of myself, learning about front end web development in order to fully express that. I utilized the tools to completely rewrite how I wanted to present—stripping away the platform-decided layout. Everything was curated.

As I grew up on the internet, my first few social media profiles were the idealized version of myself—a version that was almost always male, even as I presented as female in person. As I started going through puberty and grappling more with gender dysphoria, the internet was the place where I also learned about being transgender, where I found community that accepted me, and where I felt most comfortable existing because I could depict myself in a way that reduced my gender dysphoria.

I utilised the tools of these platforms to design a persona that I felt comfortable with—playing with which interests to visualise on my profile to make people see me as more masculine, learning how to code to hide information I didn’t want to share, and learning new design tools to try on new digital styles, or manipulate photos of my body to reduce dysphoria.

I could be anything I wanted, but, what I ended up doing was more than that—I grew into the person I had presented myself as, and my personal exploration through digital customisability was a key part of how I found that identity.

Customisability in VR

In 3D virtual reality platforms today this form of radical customisability is similarly on display. The popular social app VRChat, in development and use since 2014 to today, provides one of the most effective examples of this in action.

VRChat, VRChat Inc.

Following on from predecessors in games like Second Life, VRChat users can generate entirely custom spaces, avatars, and interactions, allowing them to design their entire experience around how and where they want to appear or act. Because no one is assumed to have one locked depiction of themselves based on their physical self, they are empowered by this norm to quickly shift between drastically different avatars. Their avatar may even shift depending on the hardware they use, given VRChat’s cross-platform accessibility from web and mobile, enabling a fluid dance between different forms of being that easily shift depending on necessity, context, or mood.

The platform fades into the background, with user designed content powering every single aspect of interaction—deciding what people see, what they can interact with, and what is deemed acceptable interaction among different social groups.

Rec Room, Rec Room Inc.

While other VR social apps like Meta Horizon Worlds or Rec Room also allow for customisability, they are often restricted in how much user designed and specialised content can be deployed. Avatars in Meta Horizon Worlds, for example, can come in a variety of body shapes via the avatar customisation tool, but they all ultimately end up taking up the same amount of floor space and users’ heights are normalised so they can’t drastically differ. These avatars present more static identities when it comes to things like facial features and expressions, while the only easily accessible customisations relate solely to changing an avatar’s clothes.

Meta Horizon Worlds, Meta

On the other hand, VRChat’s allowance for user designed avatars and spaces can be used in impressive detail, with a multiple tracking point design that can give VR users full body control, in order to conjure up something like an in-depth fictional band role-play, embodying their complex performances. Any limitations relate to what is possible inside of the Unity Game Engine, a user’s familiarity with editing, and what meets the tech specifications in order not to crash user’s systems.

You can embody avatars of any size, take up as much space as you want, and add shaders that aren’t predefined selections. You can code in interactions for the social space you are designing that match your comfort level, make your own accessibility options, and then share what you’ve made with other people. This level of customisability allows people to depict themselves and their spaces in a much broader capacity beyond the restrictions of pre-designed boundaries on identity and interactivity.

A VR Becoming

“At certain times, there are moments where I’ll become more interested in guys or I might feel a lot more feminine. And I’ve always had that feeling for the longest time. Then the beautiful thing with VRChat is that I can just switch over to that and just have that right presentation.”

Ruairí, VRChat user

Ruairí is a frequent VRChat user who has used the app’s customizability to explore their gender identity and presentation. During the pandemic, they jumped into VRChat as a way to socialize and connect with people, meeting new virtual friends through VR furry conventions that led to meeting up with smaller, more private social groups on a more regular basis.

VRChat, VRChat Inc.

These social groups led them to meeting a lot more people who were fluid in their gender presentation, including many transgender people. Much like I’d learned about my gender through the way I depicted myself on social media, Ruairí also had the experience of learning about themself, feeling the freedom to embody a different avatar in VRChat than they would have usually picked. Because they found that no one judged them for swapping avatars since many people around them used different forms to represent their gender fluidity, they decided to try experimenting with more feminine presentation.

This sparked feelings from their past that they had never fully explored, starting their own journey of self-identity and self-exploration. Looking at themselves in a mirror, while represented by a feminine avatar, they connected with a part of their self-identity.

“I remember standing in front of the mirror and seeing how I held myself and noticing how my body had shifted. Like how I stood with my legs and my hips and my like my shoulders changed a little bit and how I present myself and moved and it really clicked with a side of me that I was aware of to a degree, but I wasn’t able to express in real life.”

Ruairí, describing embodying a feminine presentation via avatar

This form of self-actualization was a powerful driver for Ruairí, who quickly moved to using more customized avatars—going onto online marketplaces to find free pre-made avatars, then jumping into purchasing base avatars that they customized with additional accessories commissioned from artists. Many of their friends have a similar level of technical ability, changing their avatars often, but customising them to have maintain a consistent color scheme, or swapping custom clothing for their new avatars to wear similar fashions.

These communities centered around customisation became important, not just for socializing during the pandemic’s social isolation, but for pushing people to explore themselves and meet others on similar journeys of self-exploration.

Digital Customisability: Looking Ahead

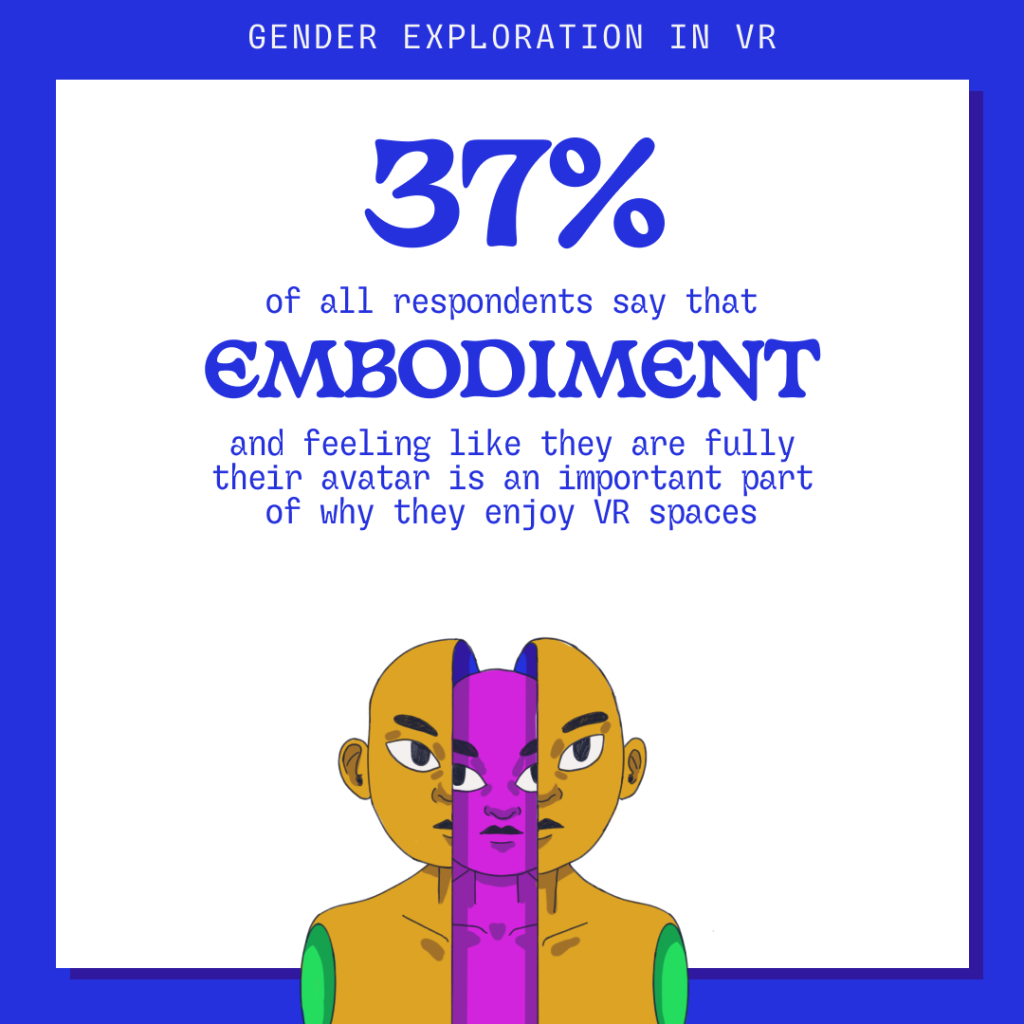

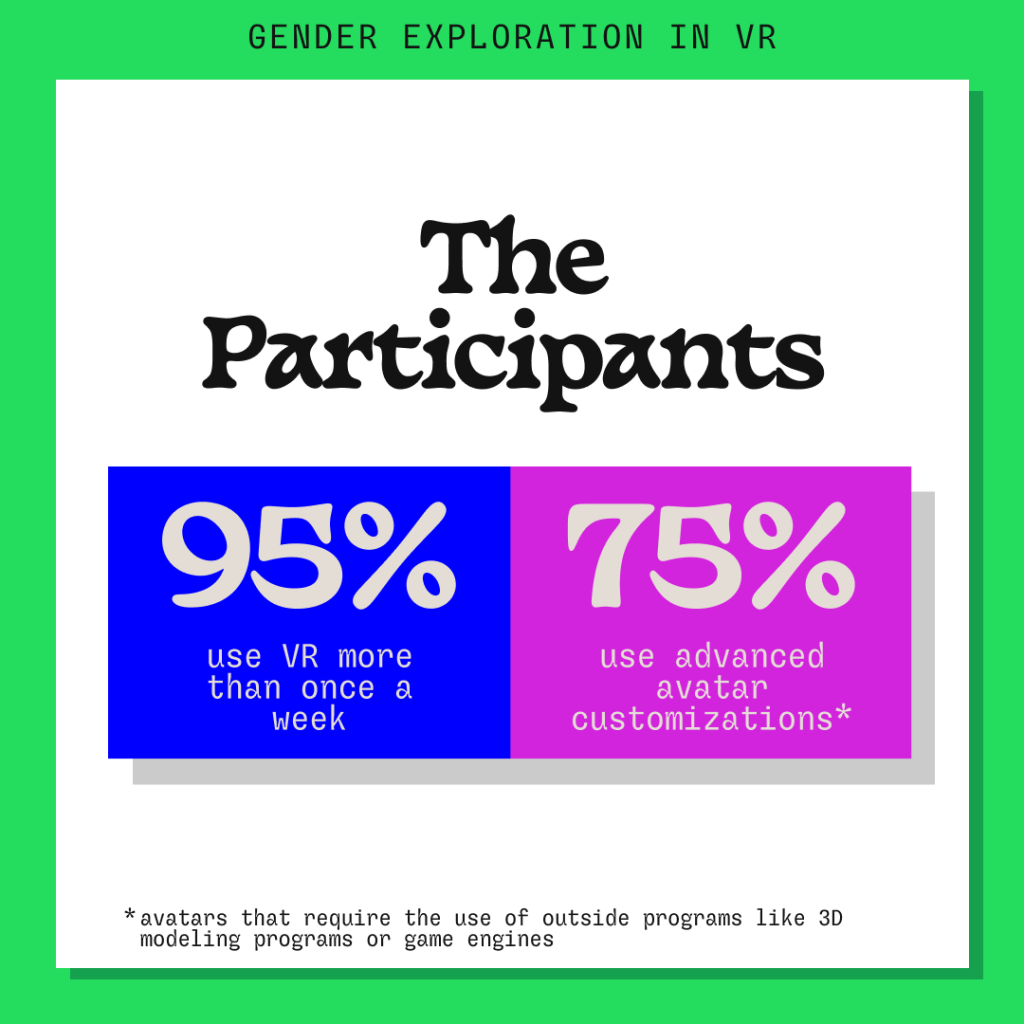

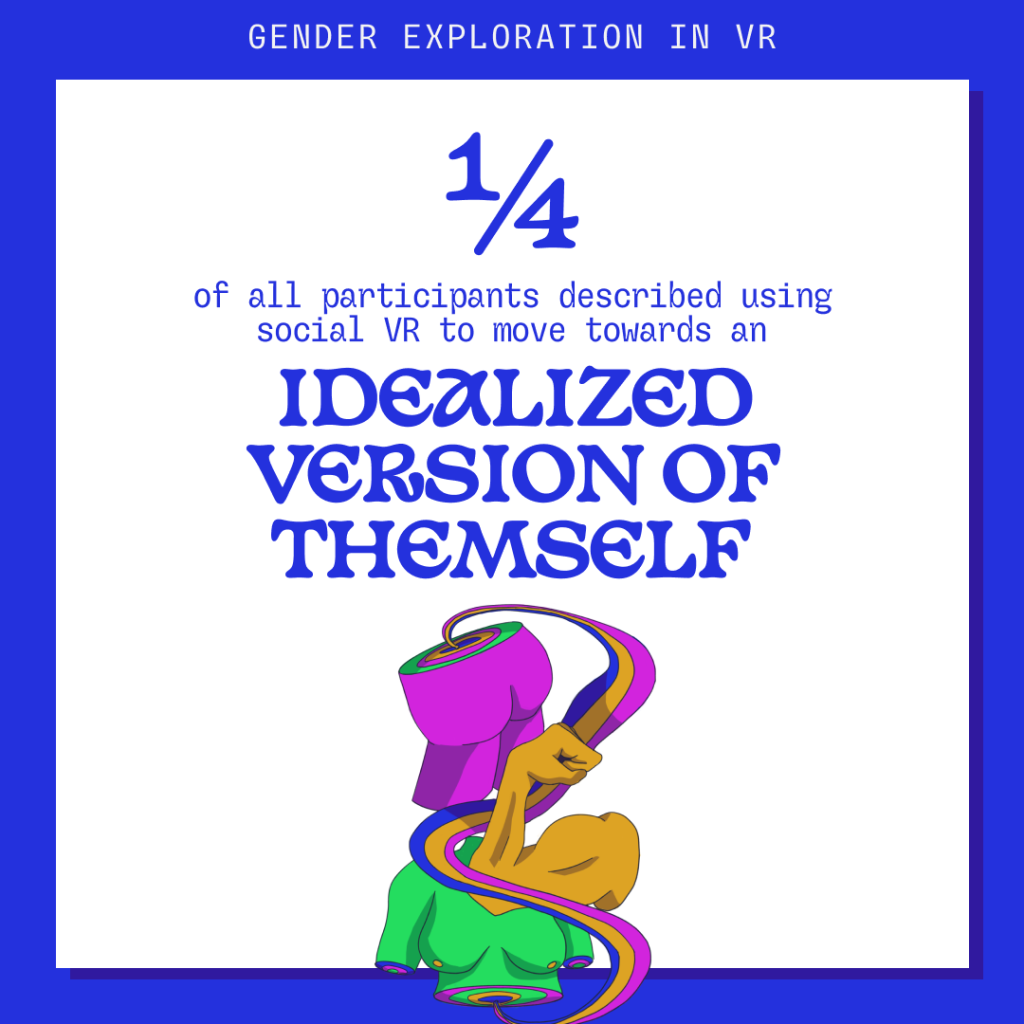

Ruairí and their friends are not alone. In March 2023, I conducted a survey of one hundred social VR space users who have used the platforms as a way to explore their gender expression in any capacity.

From transgender people using a safe space to easily change their appearance, to cisgender people wanting to try something new as a form of expression, participants of all backgrounds mentioned customisability as a key component of their investment in VR social spaces.

Social VR & Gender Exploration Survey, Zach Deocadiz

In fact, 75% of the participants had used advanced avatar customisations—customisations that required the additional use of external programs to change their avatars, such as 3D modelling programs or game engines—showing their investment in customisability through their attainment of complex game development skills in order to simply change how their avatar looks.

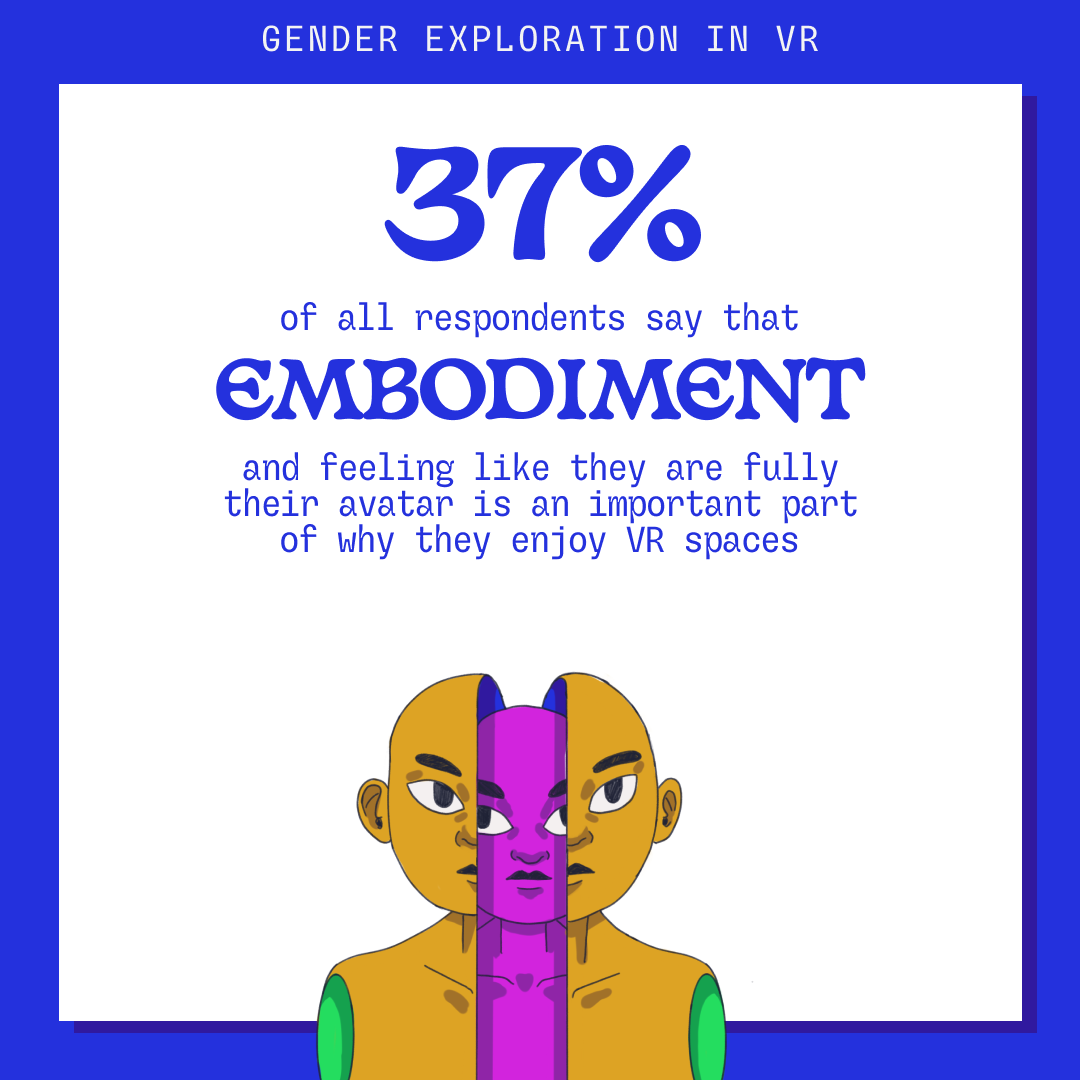

42% of participants said they use social VR as a way to alleviate social anxiety and 49% indicated that they have personally developed in some way, ranging from figuring out their identity, to building confidence and learning social skills as a result of using social VR. Many of these people attributed this to the control they have over customising their avatar directly leading to their confidence in the way they communicate with other users.

Social VR & Gender Exploration Survey, Zach Deocadiz

“The use of different avatar appearances and the ability to join and meet like-minded groups and people has allowed me to surround myself in an environment where I feel most comfortable being me.”

Cozmo (he/they), a response to the Social VR & Gender Exploration Survey

While my survey was limited in scope, these findings align with the 2022 Metaverse Fashion Trends report by Roblox and Parsons which found that 47% of Gen Z participants used their avatars to express their individuality through dressing them up and 43% of them using their customized avatars to feel good about themselves.

These dressed up avatars also allowed them to feel more connected to their peers in both the digital and physical worlds. And their avatars were likely to not be a representation of their physical self, with 45% of participants making avatars to represent a fantasy character they created, 37% trying to depict themselves as a person they want to be, and only 29% trying to replicate their existing physical body.

These trends show the general desire users have to customise appearance and how it affects the way they view themselves.

Social VR & Gender Exploration Survey, Zach Deocadiz

Nick Yee’s book 2014 book The Proteus Paradox suggests that avatars are not just influenced by us through their creation, but that the avatars themselves become large influencers in the way we behave through the way they are designed. This concept of avatar-impacting-self allows us to think of the future of what people may be able to become—in what ways can VR and social media designers push people to evaluate their behavior or guide them towards community values in digital spaces? An example like VRChat I think provides a good example of this idea’s mass appeal and effect.

I believe we are early enough in the history of VR to have these considerations and findings impact the future. VR designers should question what type of communities they want to see with every decision being made. Are users enabled to explore their potential best lives with the customisability options given to them? If VR can design for the edge cases—for the users who feel the impact of design decisions more strongly—and give them the ability of self-determination within systems, it can enable the next generation of social tool users to learn more about themselves with ease.

The early internet saved my life through what I learned by developing my understanding of self and connecting me with people who accepted me as I presented myself. How many more can be helped through choices in designing immersive platforms?