Oma: MANCHESTER, ENGLAND – Me and Morgan visit the People’s History Museum, behind it, in a corner by the water is a small plaque from 1986 dedicated to:

‘all those whose lives were taken in the first atomic bombings, 40 years ago this week in Hiroshima and Nagasaki – – – – and to all who strive to rid the world of nuclear weapons and the threat of nuclear war.’

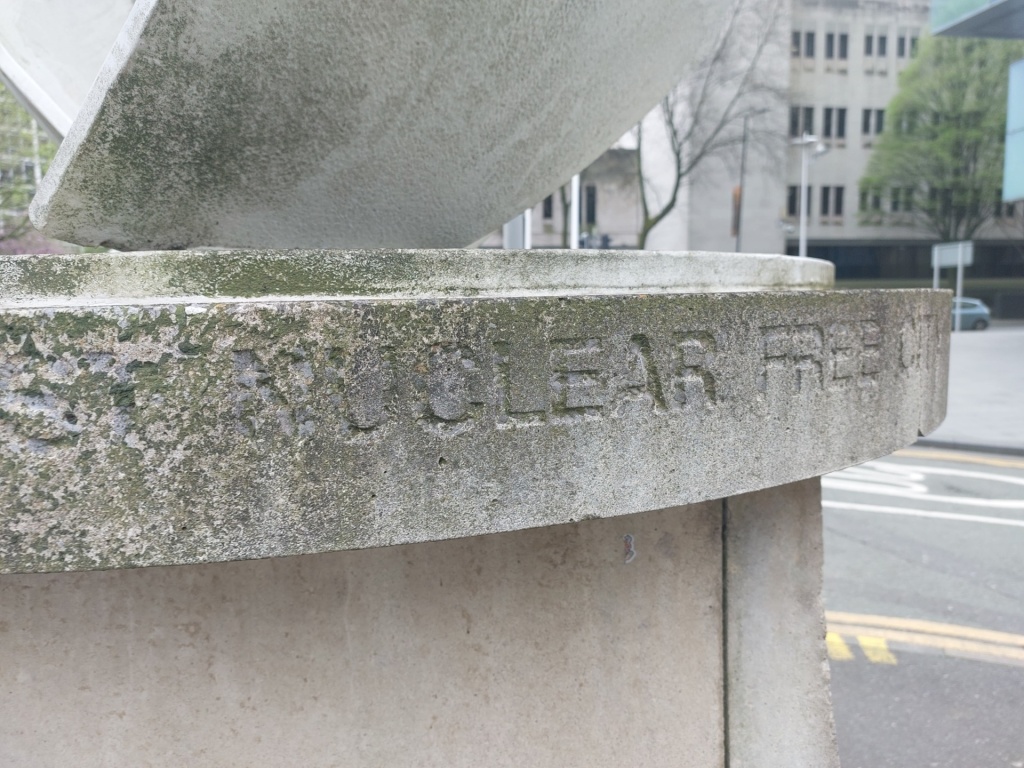

Out front of the museum is a large modernist sculpture of doves flying. Around the raised base is a carved epitaph. It is worn by damage to the stone, mostly illegible. The words NUCLEAR FREE CITY and MANCHESTER can be made out. On the front of the sculpture, in black marker pen, a swastika has been scrawled.

The north west of England was the key cradle of atomic knowledge in the UK in the middle of the 20th Century, with the University of Manchester and the Windscale site being designed to fuel the creation of an atomic arms race after the end of World War II. In 1980 Manchester declared itself Nuclear Free, the first city in the world to do so.

Today, markers of this aim like those above are left in the landscape of our cities, markers of technological regret.

Doves of Peace (1986)

While England’s political leaders stoke the fear of, and repeat the necessity of, the nuclear weapon in a race for an election that will shift the political landscape of the country, the reality of that threat feels distant compared to the known atrocities which the UK has provided weaponry and military force to commit, for my entire life, and yours. Which it provides today in the occupation of Palestine, which presses as a more urgent need to prevent further death than fictional nuclear wars, and should like any international mass killing fall under the UK’s responsibility to protect. It feels distant compared to the known colonial crimes of atomic testing that took place all throughout the era of ‘the bomb’.

The politics of fear around nuclear weapons today is disengaged from historical and lived realities. One such being that the UK has experienced a nuclear accident, at a site intended for creating made atomic weapons. Another that that site is today still considered one of the most dangerous nuclear sites in Europe.

This disconnect between history, political fear, and nuclear reality is tied to the North as a location, and to the history of video games as an art form, and it’s in these places that Me and Morgan have been researching, and planning a site of response – called Wormwood.

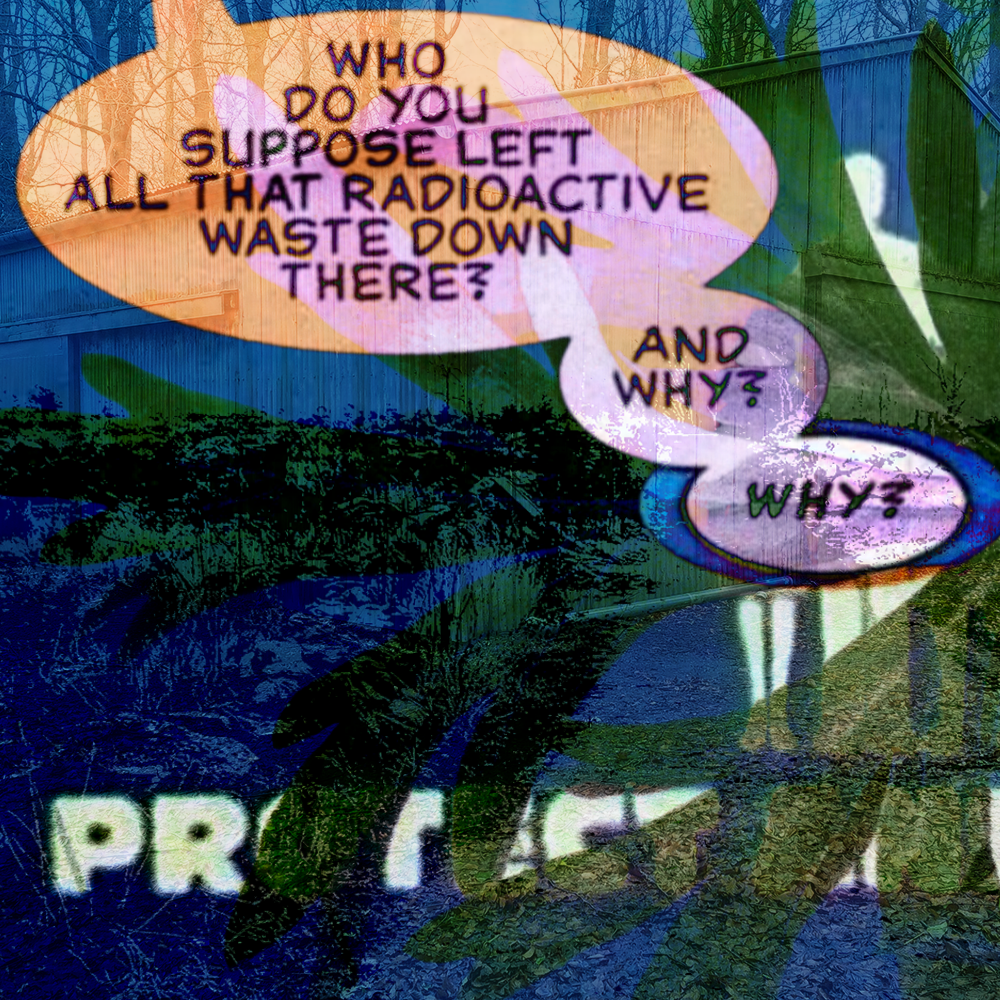

Wormwood Collage (2024)

Morgan: Since 1947, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists has maintained the Doomsday Clock, a symbolic countdown depicting “how close we are to destroying our world with dangerous technologies of our own making.” The closer to midnight it gets, the closer we are to destruction. 1953 would see the 20th century’s closest brush with the apocalyptic witching hour – the invention of the hydrogen bomb, pushing the hands to two minutes to midnight.

In 2023, it reached 90 seconds. With the Russian invasion of Ukraine extending into the Chernobyl and Zaporizhzhia nuclear reactor sites, and the already fragile New START nuclear weapons treaty on even shakier ground, the threat of nuclear disaster or even nuclear war is closer than ever. Since 2007, the Bulletin has also considered climate change in its hand-setting deliberations, the time to midnight only decreasing ever since.

In January 2024, myself and Oma Keeling planned to visit Sellafield, still looming power plant, now nuclear storage site and home to various projects of the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority, in Cumbria, as research for Wormwood. Born from our shared interest in industrial decay, haunted landscapes and video games, Wormwood is an analysis of the role of nuclear power and disaster in virtual spaces, and how it mirrors catastrophe and complexity around nuclear power and other industries in the North of England.

Wormwood Collage (2024)

The name itself has many meanings. There is the prophecy from the book of Revelations:

“The third angel blew his trumpet, and a great star fell from heaven, blazing like a torch, and it fell on a third of the rivers and on the springs of water. The name of the star is Wormwood. A third of the waters became wormwood, and many died from the water, because it was made bitter.”

This prophecy is often connected to the Chernobyl disaster, “the waters turning bitter” referring to the land and water surrounding the plant left irradiated and uninhabitable, and Chernobyl itself being the Russian word for the plant. But we are also interested in Wormwood as a nuclear *plant*, something to be grown and cultivated, a rhizome of strange coincidences and a haunting background radiation.

Frequency illusion or no, the memetics of nuclear kept appearing in the strangest of places. On a Christmas walk over Birkrigg Common, I found a Bronze Age stone circle. Across the bay, a nuclear power plant, both as hidden as each other. While I’ve played several games for the sole purpose of Wormwood research (Metro 2033, Stalker: Shadow of Chernobyl, Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare), I had not expected the opening of Half-Life (1998) to so perfectly mirror the doomed tests at Chernobyl.

DOOM (1993), a game I’m re-re-replaying as a break, even calls its green goo “nukage”, an offhand choice of hazard that adds corrupt flavour to the nebulous evil organisation, the UAC. Nukage is the most common hazardous floor type in the first episode, and as such is less damaging than “hellslime” or indeed “super hellslime”, and is one of the few things in the UAC that seems meant to be there, judging by the preponderance of nukage barrels dotted about the facility.

panels from a DOOM comic book

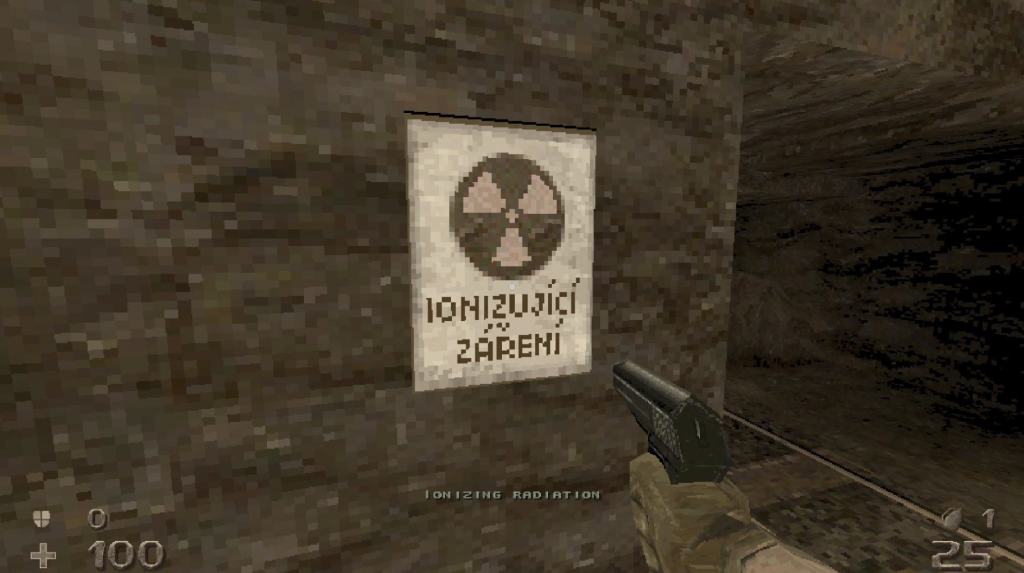

Of all the games I’ve played, it’s only HROT (2023), the one person passion project FPS which blends Soviet Czechoslovakian nostalgia and pulp paperback sci-fi/fantasy, that bothers to depict the mining of the material that makes all this green goo possible. Its gas-masked enemies vomit before approaching you. Rooms for contaminated clothes and shelters dot metro stations.

Oma: For more on this part of our research, we gave a talk on it at the Pervasive Media Studio in January 2024, which you can watch here. It includes for instance how Half-Life itself manages to have obscured the actual extractive nuclear history of the region in which it’s set.

HROT (2023)

Morgan: For our analogue adventure, the acceptance of non-abstracted physical hazards in a situated space became crucial too.

We had not anticipated Storm Isha. Inviting Oma to my family home in the Lake District also meant inviting them to experience the wonderful intersection of Northern British weather and Northern British infrastructure, or, the lack thereof. Despite our best efforts and general stubbornness, the rain won.

There is something poetic about that- rain-struck, wandering through trees flattened by Storm Arwen in 2021, and unable to reach what to some is climate saviour, the only reasonable way to meet ever increasing energy needs, and to others a time-bomb, born of compromise and general non-committal to genuine green energy.

Defeated by the elements, we took refuge in my parents home, watching documentaries of bureaucrats talking about how Necessary it was for Britain to have hydrogen bombs, lest we be left in the dust (this was how we learned that Sellafield, then Windscale, had been born specifically to feed the nuclear arms race), and atomic sci-fi, from the more interesting to think about than actually watch These are the Damned (1962) to the archetypical raunchy green goo shlock fest, The Toxic Avenger (1984).

It was also a chance to discuss in person what we want Wormwood to be, for our thoughts to cohere into something more concrete. Wormwood sits in an imagined “Northern Exclusion Zone”, an abandoned nuclear plant frozen in a radioactive , a monument to the shaky-grounded futures imagined in 70s Britain. Within this monument will be contained prose, poetry and analysis of the ways virtual worlds have attempted to grapple with nuclear power and disaster, a matryoshka of our own attempt to portray the unportrayable.

Unable to reach Sellafield, we retreated to Manchester, a new home that has yet to settle into the contours of my mind, fragmented spaces intersected with tram and bus routes, not yet a contiguous whole. So it’s perhaps not surprising that despite its central location, I had walked past the British Nuclear Test memorial so many times, a small plaque dedicated to those who had died in the Empire’s attempt to hold onto the world with warheads.

Another strange hidden corner – the Guardian Underground Telephone Exchange, a nondescript brick building surrounded by barbed wire and razor spikes, unmarked and unremarked upon by any signage, yet it was designed to protect emergency communication cables from nuclear war. Certainly it makes sense that its existence was kept secret during the cold war, but its current anonymity and intense security is puzzling. I’m reminded of Fiddler’s Ferry, a mausoleum monument to coal-fired future that never occurred, more buzzing with activity now that is being torn down, surrounded with threats of reprisal to put off urban explorers.

The Guardian Underground Telephone Exchange, Manchester

A few days after our trip, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists released their annual report. It is still 90 seconds to midnight. No significant enough commitments to combating climate change or military de-escalation have occurred to change the pessimistic figure.

Reading book after book dedicated to the horrors of radiation has made it difficult to trust a government constantly chipping away at every public good with apocalypse machines.

Threads (1984), the infamously harrowing made for TV movie, asks a simple, bleak question- how would Conservative Britain deal with a nuclear apocalypse? The answer it gives is equally simple – it wouldn’t.

While I can’t imagine how it would have felt to watch it during the height of the Cold War, what was most striking was how little seemed to have changed in the forty years since it aired. Though a specific year is never given, and the government never explicitly addressed, it’s clearly Thatcherite Britain, with all the commercial excess and labour strife that implies. With a current government explicitly invoking Thatcher every chance it gets, and an opposition more than happy to jump into a New Labour soft conservatism, the sense of deja vu is palpable.

In the hour before the bomb drops, the government is shown to be both woefully underprepared and more focused on projecting a paternalistic order to Keep Calm, an eerie analogue to the Johnson administrations horrendous response to the Covid pandemic, one that becomes even more sinister post drop as council bureaucrats ponder whether its worth feeding the sick at all, whether or not such a disaster has an acceptable level of death out of compromise.

Plaque dedicated to those killed by nuclear bomb in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 1986

Oma: Wormwood exists as a space to locate our thoughts and feelings about nuclear energy as its emerged to us over our lives in a space and over the course of the research laid out above.

Feelings of neglect, comical disgust, fear, the promise of the future and the nihilistic expansion of past events, these all mapping onto our matrices of identity, circumstance and ideology. Each of our realities shaped on the massive universal level, the subatomic, and that at which we meet most often, the world we inhabit.

If nuclear power is here, nuclear waste is here in the north, south, east and west of the UK, the World, what we wanted was a space, a locality, a land that could be reimagined under the banner of sub-atomic particles as their socially integrated, terror stricken real.

A casket, a zone, a future where our disaster inflicted minds might live fixated on one matter, one issue. In video games, this promise is often made, just as in art, an adventure about family, a reflection on capitalism, and often in genre fiction, the place where our language of nuclear atrocity and accident is usually located, we take these things, we empty them of our contexts in order to fantasise. But, to connect these to the land we needed the past and our fictions of the past to flood in, to be questioned and confronted by the history of the subatomic sciences in the UK. Open any gate to the past and you allow in things you didn’t know, things that are upsetting or unsettling.

Most unsettling has been the lack of competency in dealing with the consequences of matter. The attempts to hide near disaster, the lack of knowledge, the pushing of dangerous materials past a limit and the effects this can have on a large population. If a space of exploration, Wormwood is one where I am sitting with this thought, and with knowledge of its occurrence throughout nuclear history. That our safety and our lives have less to do with reality to the people who have permitted nuclear actions than the symbolic achievement of a political advancement. It is a technology of personal interest, in line with those others that drive the destruction of the climate.

In my ideal Wormwood, I sit on the grass of the exclusion zone, a hill overlooking the plant and its cooling reservoirs, weak and sweaty, my shoulders release some tension and I smile, I’m home, inside the wood that bore my soul right out of the forest of immediacy, a green thread plucked out of one of my follicles, caught on a rusted door. All doors here rust too slowly. Something in the air maybe