A description of the moments leading up to François Mackandal’s final flight opens Hope Strickland’s film I’ll Be Back! (2022).

It’s 20th January, 1758

And a crowd is gathered in what’s now known as Cap-Haitien

The rebel slave, François Mackandal, is to be burned alive at the stake

Mackandal is condemned not only for his crimes

But for his radical powers of metamorphosis.I’ll Be Back!, Hope Strickland (text from video, 2022)

The film has within it a tangled web of relationships to this moment, in which François transforms into a fly to escape his death, crying out the film’s eponymous phrase.

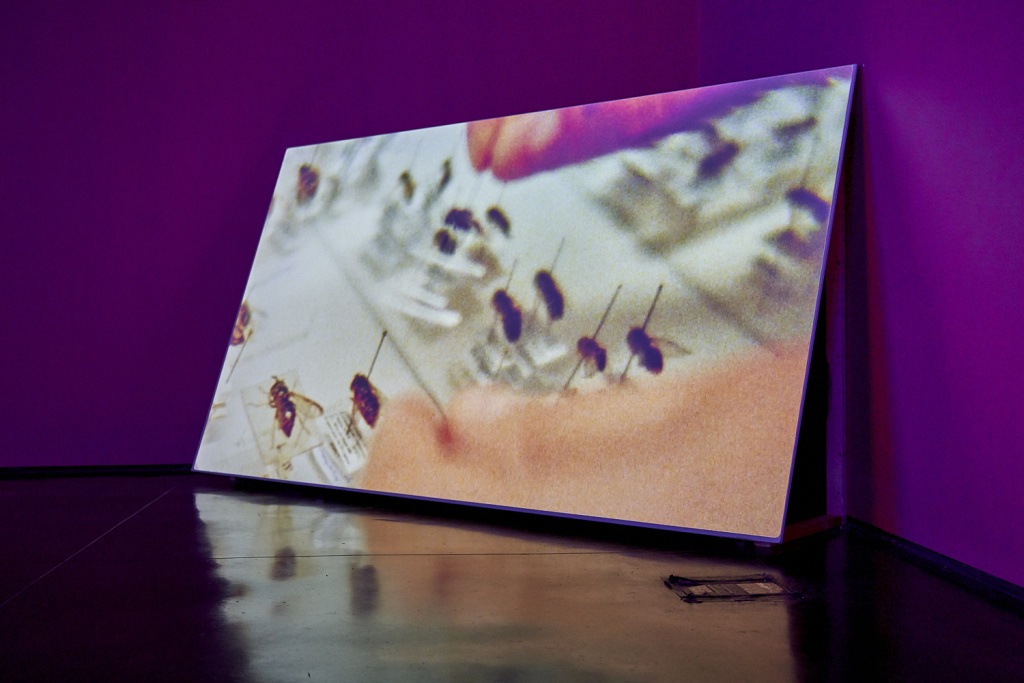

I’ll Be Back!, Hope Strickland (video, 2022)

Through a range of filmmaking materials that interact arrestingly with the institutional nature of archival material of colonialism and slavery, I’ll Be Back! moves from a pinned insect in the collection of a British colonial lieutenant, shot by Hope in 16mm, to HD footage of rooms empty of people, filled with cabinets, to century old film footage of a white man’s holiday in the Caribbean, onto a shaking camera, tracking a flying object to an unknown location.

This is, in how Hope incorporates archival materials, partially an attempt to create something that speaks to “the distances between myth and truth.” It’s as she points out, a thing that forever exists, from inception, in the experiences of, and subsequent teaching and writing about enslavement. A relationship with ‘truth’ that holds dehumanisation as natural.

I’ll Be Back, Hope Strickland (installation, 2023), Photo © Rob Battersby

This complexity of personal relationships, to learning and physical existence of the histories of slavery and colonialism, runs throughout the film. There are moments which Hope describes as “charged”, like the unfolding of a slave ship diagram in a museum archive, and her feelings, and sense of being observed, as a Black woman at that moment, is just as much the focus of the film.

A key moment Hope talks about is the presentation of the origin of a colonial collection of insects in a manner that starts off with a defensiveness about the collector’s role as a colonial Lieutenant. This was an unprompted disclosure, something Hope links to her presence as a Black woman in the space of the archive. This experience plays out in the film as a morbidly funny fact-checking of the claims made by the curator who offered the insight, using screen recordings of Hope’s Google searches, which easily dispute the idea of a non-violent colonial presence, as that defence is presented in voice over.

I’ll Be Back!, Hope Strickland (installation, 2023), Photo © Rob Battersby

These experiences are dealing with what Hope refers to as the “vexed temporality” in the way that contemporary Caribbean life and its global resonances, is distinctly and deeply layered with histories of exploitation that keep returning.

It is also in conversation, Hope says, with the ideas of Olivier Marboeuf’s 2021 text Towards a de-speaking cinema (A caribbean hypothesis) in which the story of Marakand’s metamorphosis acts as an example of his theory of a cinema that moves away from fatalist repetition, avoids replication, incorporates myth, to address time otherwise.

“[cinema] had to speak differently and from another place than the place where subordinate speech had been assigned to be spoken – in other words, a place from which it could not escape. A scene that was both in the service of the comfort of certain people and under the power of certain laws. A scene of life that was also a scene of death.”

Olivier Marboeuf, Towards a de-speaking cinema (A caribbean hypothesis), 2021

In the way that I’ll Be Back! presents an agitation towards archival situations, it explores the boundaries of a film in the position of the type of documentary making that Marboeuf urges flight from. There is an inherent questioning to the image and knowledge making in these spaces and awareness of the stricture. It is as Hope describes it, uncomfortable, tense, violent, and displays the way in which these feelings that Marboeuf notes as underlining the difficulty of cinema that ‘speaks’ arise.

I’ll Be Back!, Hope Strickland (video, 2022)

As the film goes on and reaches its conclusion, there is in Hope’s editing, a moment where the reversing of a clip of a travelling explorer type in a 1926 travelogue in the Caribbean, making him walk backwards, displays the fact that the material, the film, the archive, and all the power it is meant to have, is illusory.

The work was created during Hope’s residency at FACT Liverpool, an experience she looks on positively, and has to it a relationship with the North of England’s collections and histories. It is presented as part of FACT’s Radical Ancestry project of 2021-2022, and exhibited at the start of 2023 alongside Ashley Hope’s work, in a space designed by Chila Kumari Singh Burman.

Worlds Meeting At FACT

Visiting FACT on the 15th February, 2023, at a presentation announcing their 2023-2024 programme, the artist Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley presented a short overview of how her exhibition – When Our Worlds Meet – came to be in collaboration with The Bandidos, a group of young people in Liverpool aged between 11 and 17.

The exhibition contains, in amongst a multiply layered space designed to fit the wishes of the kids, a series of distinct CGI interactive videos, presented on screens of different size and interacted with via arcade joysticks. Installations of cubby holes and play equipment and an entire living room spread out through the space, the whole thing looked over by walls covered in writing and banners representing the kids.

When Our Worlds Meet, Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley + The Bandidos (exhibition, 2022), Photo © Rob Battersby

It is presented alongside Josèfa Ntjam’s installation When the moon dreamed of the ocean (2022) as another piece of the Radical Ancestry project.

As Danielle says, talking to Container after the event, her research and work, in digital presentations like BLACKTRANSARCHIVE.COM, developed as a need to see the people around her in archival records, “I was trying to find representation of the people that were existing around me, Black trans people, in the archive, and I couldn’t find any.”

She talks about finding sources, but only in ways that recognise the history of trans people as being “archived in the same kinds of violence that trans people experience now.”

“And when I saw that, it got to me, because I realised no-one had been archiving people that are around me all the time and it felt really strange that transness and those in my community are seen as new, and they’re not new, it’s not even like a cool trendy thing it’s just something that’s existed for a long time.”

The idea then, was to respond to the urge in western culture to deny archives of trans-ness, “I kind of wanted to begin to archive things now, so that those of us in the future have something to look back on so they can’t say ‘oh, this is new’ again in 200 years.”

When Our Worlds Meet, Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley + The Bandidos (exhibition, 2022), Photo © Drew Forsyth

Talking about the process of creating an archive like that, and moving into this type of installation based exhibition, Danielle talks about a shift in approach, “At the beginning of trying to build an archive on BLACKTRANSARCHIVE, I didn’t know how to do it, I didn’t know what I was doing at all. Often I would ask the question ‘What do you want to archive about yourself?’ and no-one had an answer, I don’t have an answer, it’s such a hard question, if you ask yourself, it feels almost useless to archive anything.”

“A lot of what I’m looking into now is the messiness of social media, and how useful and un-useful it is at the same time. Often people are like, ‘ah it’s a cesspool’, and it is, because we are, we are a cesspool of mess.”

“I think at the beginning of archiving I wanted to say ‘these are people, this is a story they wanted to tell’, and that’s still in the work, but, I think moving to this it’s more about giving over control of something to try and capture that snapshot, and knowing that anything just translated through me is not going to be enough.”

“And to have them come in and draw over the wall, and making these posters and writing whatever they want and there not being a moderation process, there’s a lot of wild stuff written everywhere, but, that’s part of it. I think sometimes as artists we can get quite clinical and picky in what we think is appropriate and not appropriate, and especially also in archives, that’s one of the main problems.”

When Our Worlds Meet, Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley + The Bandidos (exhibition, 2022), Photo © Drew Forsyth

The archive creation process, rather than being a fixed and catalogued collection then, becomes a spatial evolution instead, one that is designed to accommodate the creation of sharing, “That’s something I’m very happy about with the space actually, because it doesn’t feel like mine. There’s a lot of decisions that I wouldn’t have made and that’s the best thing about it because they made them.”

The creation of the space itself was a long process, taking over a year, and deviated quickly to being a collection of wild dreams and self-representations, given out in a way that defied expectations. “We asked what do you need in Liverpool? And they built their areas, they were completely wild, Dragon Town this that and the other, and then we spoke to them and designed an avatar for each of them to represent them, again and I thought these avatars might be human, but no.”

“It became more like an amalgamation of all the things they were thinking of, and interested in and liked, and thought that could be in a world that they would like to run around in.”

Turning a series of recordings of that nature into a digital world, and then taking parts of that world and physicalising them, was the process that created the room, “We mostly modelled everything in Blender, and we also used this very simple one called Fotoanim, which is a terrible program, made by one youtuber, who no longer makes videos, and it will let you do is put in a photo, cut it out, and make it 3D.

That was really helpful it helped me to prototype really quickly, and made things from images they had made, and that was really helpful, originally I was modelling everything bespoke.”

When Our Worlds Meet, Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley + The Bandidos (exhibition, 2022), Photo © Drew Forsyth

Once they had this collection of material, there also came a kind of rethinking of the personal relationship to this project and the space, “The idea kind of came that okay, if we were going to build a new place, we kept talking to them about this new place that they would like, we should actually build a place that they could go after school and chill in, do whatever they want in. So that idea of let’s actually build a space that’s all theirs, rather than to display their work, the space is their work, kind of took over.”

“We started taking things out from being in the game we’d been basing on their responses and putting them in the space. Instead of swings being in the game you’re just on the swings in real life. Another one there was a meat world, and so okay we can put that in a butcher’s.”

“It’s really hard to figure out what the aesthetic should be, how clean, how gallery, but in the end we just went for mess, full ass house mess. Originally the butcher’s was full of candy and crisps that you could eat, and that they did eat and they just destroyed it and ransacked it.”

Collecting Music and Creating Versions

The event on the 15th ended with a performance of sound work by FACT resident Ashley Holmes and collaborators, a re-working of Ashley’s multi-channel audio work and installation Decaying Tail Of A Sound.

Speaking to Container before the event, Ashley talks about his relationship to archives, which is a thing, he says, that like many other things, comes from music.

“The ways it’s collected mainly, like from a fan level. I was in my mid to late teens around the mid-noughties, so grime music was really important for me, in terms of it being sort of a technological shift, in terms of people utilising digital space in a different way, in terms of how the music’s produced, in terms of how it circulated. Things like radio broadcasts, like series of DVDs that came out around the time that gave faces to these voices that you would only hear on the radio, or on mixtapes or tunes.”

Decaying Tail of a Sound, Ashley Holmes (installation, 2023), Photo © Rob Battersby

He also sees this collecting lineage in his background, “My family are Jamaican, and so a lot of reggae music, a lot of records, a lot of tapes, and radio again.”

There’s a reason that music has become important that lies in the contexts for Ashley. “More and more recently, I’ve been really interested in some of the conditions that that music’s made under, and outside the people as individuals and as artists how they become a way of storytelling I guess, a way of retracing different social and political pasts.”

His process, with recording, editing and mixing sound, has been developing in the past five years or so as a way of interacting with presenting and investigating these collections.

Decaying Tail of a Sound, Ashley Holmes w/ Ratiba Ayadi & Seigfried Komidashi (performance, 2023), Photo © Rob Battersby

“Some of the stuff I do in a DJ capacity and radio broadcast just bringing together different music and time periods, and I guess a lot more invested in it as a research process, about reggae music, and thinking about specifically dub music over the last couple of years, and the ways that it has allowed me to make relations and connections between different places, different geographies.”

“And also understanding on a studio production level what happens, finding connections in that. So them being iterative, sound system dub culture for example informing the ways that grime is performed, in that there’s a set up with DJs and a host or MC with a microphone, and there’s a direct response or relationship to the audience in how they cheer or egg someone on, that’s something informative.”

Asked about what kind of archival process interests him, Ashley states that he’s more interested in “the unofficial ways things are collected and gathered, which is maybe turning to a personal collection or an alternative way of people thinking about how they learn about knowledges, cultural histories, how the music might tell a story of a specific place or specific trade.”

Decaying Tail of a Sound, Ashley Holmes (installation, 2023) Photo ©, Rob Battersby

This all comes from being a listener, not just to music but also the dissemination of information in conversation, “Mostly through radio shows, and podcasts. There’s a really brilliant one called The Strangeness of Dub by Edward George, from the Black Audio Film Collective. I think there’s about 10 episodes that were broadcast through Morley Radio, London, where he just talks through people like King Tubby, people like Prince Jammy, like Scientist, some really key pioneers and producers in the genre, and then contextualises them in a philosophical framework and thinking about things like other forms of avant-garde experimental sound practices.”

“Conversations as well, outside of the actual music, conversations that people have recorded, these aural archives, something like On Beat Merseyside, is specific to Liverpool’s history in musical terms in relation to reggae music in the 70s and 80s.”

“I also found a lot based in Sheffield, in a place called SADACCA, a social club/community centre that’s been around since the early 70s. More recently they’ve been going through different processes of collecting and gathering stories of people that live in the immediate surroundings of the community, and a lot of those are about music. They open up another pathway to go ah right, who was that person? Where was that venue?”

When we talk about archives there is a belief in a static record, one that both Hope and Danielle address and critique in their work, and in researching music like dub, there is an essential rejection of a definitive and singular experience.

Decaying Tail of a Sound, Ashley Holmes w/ Ratiba Ayadi & Seigfried Komidashi (performance, 2023), Photo © Rob Battersby

In discussing how he was translating his work into a live performance for that night, Ashley makes a connection to this culture, “It comes from the idea of the version, which is really prominent in reggae music and dub music, and this culture of remixing, or redoing, having multiple versions of the same thing that exists.”

“In dub or reggae music you’d have often a 7inch vinyl single with the more popular track people might be familiar with on the A side, and on the B side the dubbed version would be a little bit more experimental. There’d be quite often a lot of vocal remove, there’d be a lot of reverb mix audible, with the percussion and the drums, and there’s space in that, and that space was often utilised as a kind of invitation, as potential for somebody else to add their own voice to that conversation as something that they have. There’s examples of twenty plus musicians all on the same instrumental in different forms because they’ve made use of the B side.”

“I’m kind of thinking about the static version of the work being one side and a way of stretching out and leaving space for me to kind of re-perform in a live context, to kind of mimic that process of the A and B side, and the dubbed version of something.”

The Future Past

For each of the artists there is a developing relationship to archival forms and capturing the living interaction with them, their different forms and complexities, especially as regards to how the official record has excluded or not provided for black life.

Interested in how, with a relationship to archives, this work will be captured or represented for the future, they all also see this in a more complex way than simply filing it away in a cabinet somewhere.

I’ll Be Back!, Hope Strickland (video, 2022)

“The film has had its own life,” Hope says, “It’s travelled further than I have at this point”, reflecting on it being out of her hands since its completion in the early spring of 2022. A key impact of the work on her process has been an interest in film that has continued on from the work and into what she is doing today. There is a flexibility and dynamism to the form and to capturing it that allows for a different type of interpretation, and also “doesn’t mean sitting around in a room staring at a screen all day, well maybe a bit of that, but a different kind of screen.”

For Danielle the prospect of taking the exhibition forwards is an exciting one.

“Something I’ve really wanted in the practise is actually revisit every project, and like games do remasters, like recently there was the Dead Space remaster, I want to do the same with these projects, respeak to everyone and reappropriate it for the modern them as if they’re the new modern audience.

When Our Worlds Collide, Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley + The Bandidos (exhibition, 2022), Photo © Rob Battersby

“I don’t feel that archives should sit still, I wouldn’t want to show the same thing again, for example BLACKTRANSARCHIVE we just updated it, and so now we’ve got Australian Black Trans people in it, and we’re gonna keep doing that.”

“With this particular show, I would love to revisit all the young people in the show, and then do a whole new version of everything, just to archive that new snapshot, and so we have these different versions of the snapshot, and if the project continues for ten years, then we can show all three, one room is this show, one is the next, that would be awesome. If we had the money to do it.”

Decaying Tail of a Sound, Ashley Holmes w/ Ratiba Ayadi & Seigfried Komidashi (performance, 2023), Photo © Rob Battersby

Ashley sees the work as needing to continue in a way too, “At this stage it feels early on still, thinking about the local history but also thinking about more widely the stories and experience of black communities in a British context, so I’d be quite interested in something I do with a couple of projects, in facilitating a listening space, a discussion space, that is maybe is less about things being produced and made but more about ways of creating additional collective listening experiences, maybe in a way that there’s more of a way that people could contribute as a discussion. I think that’s kind of one of the next things I’ve got.”

In this way, with the work they’ve been creating Hope, Danielle and Ashley present a complexity of multiple engagements with archives, collecting, rejecting and redefining what is represented across film, story, music, and digital and physical spaces.

Illustration © Lucy J Turner